La Follette School of Public Affairs Agency Political Ideology and Reform

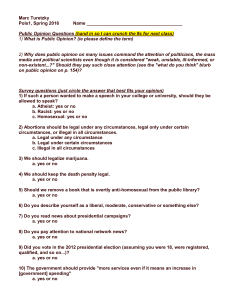

advertisement