I A S

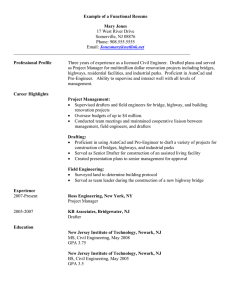

advertisement