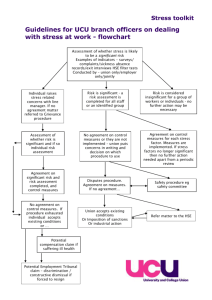

Work-related stress A good practice guide for RCN representatives

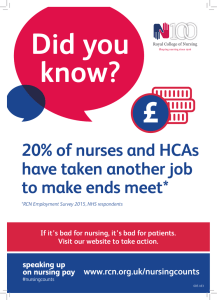

advertisement