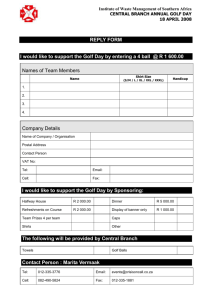

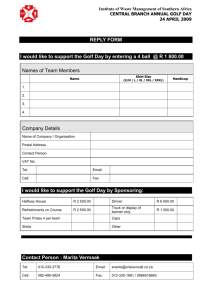

+ 2 (,1 1/,1(

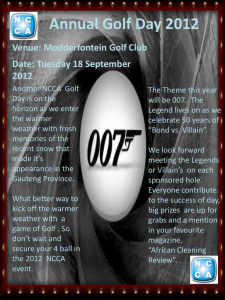

advertisement