C T “I

advertisement

CHAPTER TWO

“INTERNATIONAL LAW IN CONTEXT:

THE KOREAN PENINSULA 1950-1999”

The readings below focus on a particular place at two particular times.

The place is the Korean peninsula. The times are the early 1950s and the mid1990s.

The chapter is in three sections:

The Korean War and the United Nations

The Korean War, the US President, and the US Supreme Court

North Korea, the United States, and Nuclear Non-Proliferation

Chapter One introduced you to international legal concepts, but it did so

without much reference to particular legal rules or to the application of those rules

to particular facts. The readings on theories of international relations in the fourth

section of Chapter One introduced you to the potential applicability of politicalscience theory to questions of international law, but, like the ICJ Statute and the

excerpts from the Restatement of Foreign Relations Law in the second and third

sections of Chapter One, these readings lacked much in the way of specific

references to particular laws or facts.

This chapter, in contrast, is aimed at examining some specific rules of

international and US law as they operated against a specific background of

political and historical facts.

56

INTERNATIONAL LAW IN CONTEXT

In doing so, we’ll examine in some detail lawmaking and politics at the

apex of the hierarchies of international and domestic law: the United Nations (for

international law) and the US Supreme Court (for domestic law). We’ll examine

laws about what are in some sense the first principles of the international and

domestic legal systems: the idea that the United Nations should act to prevent

threats to international peace and security, and the checks-and-balances idea that

the Supreme Court interprets the Constitution to constrain the President from

acting without sufficient action by the Congress.

You will recall (from Question 2 of the Six Main Questions in the first

section of Chapter One) that there are four main areas of concern in international

law: foundational issues of the international legal system, security, economics,

and the commons. Chapter Three and subsequent chapters focus on some

particular aspect of one of the four main areas of concern. This chapter is mostly

about security-related issues—the response of the United Nations to cross-border

aggression, the President’s power to take actions based on the fact that US armed

forces are engaged in active hostilities, and the proliferation of nuclear weapons—

but the conceptual emphasis is on these issues as representative of the

international legal system as a whole rather than as a distinct sub-topic within

international law.

Sections One and Two of this chapter both involve legal questions arising

out of the Korean War, which began in 1950. (Active hostilities ceased in 1953,

although no peace treaty among the combatants has been signed as of this

writing.) Section One involves matters of international law, i.e. the actions of the

United Nations. Section Two involves a matter of what one might think of as

domestic law, i.e., an opinion by the US Supreme Court concerning the

constitutional authority of the President. Nonetheless, the controversy at issue

flowed directly from the Korean War, and the opinion addresses the President’s

powers to take action based on national-security justifications. Section Three

examines much more recent events: the actions of the United States, North Korea,

and other nations in the 1990s concerning the possible or potential possession of

nuclear weapons by North Korea.

CHAPTER TWO—A CASE STUDY: KOREA

57

58

INTERNATIONAL LAW IN CONTEXT

Background (Optional) Reading:

A Very Brief History of the Korean Peninsula

For those of you who haven’t previously studied Korea, here’s a very brief

overview of events in Korea between 1393 and 1998.

Generally. The Korean peninsula was the site of a single, independent nation

(ruled by one dynasty, the Choson) from 1393 until 1910. Japan occupied (and to

some extent colonized) Korea from 1910 until 1945. In 1945, the northern portion of

the peninsula was occupied by Soviet troops and the southern portion by US troops.

Between 1945 and 1953, the division of the Korean peninsula into two nations—a

communist North Korea and a non-communist South Korea—ossified with the

beginnings of the Cold War and with the Korean War. The Korean Peninsula remains

divided into two nations to this day. South Korea’s official name is the Republic of

Korea (ROK); North Korea’s official name is the Democratic People’s Republic of

Korea (DPRK).

The Korean War. The early 1950s saw the Korean peninsula ravaged by the

Korean War. The Korean War was the first significant employment of the rules and

procedures of the United Nations as an instrument in an international crisis (the

subject of Section Two), and it also led to an important case in the US Supreme Court

on the limits of presidential authority (the Subject of Section Three). The warring

nations signed a cease-fire agreement in 1953 but have yet to reach agreement on a

formal peace treaty.

North Korea and Nuclear Proliferation. The mid-1990s saw the world’s

attention return to the Korean peninsula when North Korea, a dictatorship of Stalinist

thoroughness and more-than-Stalinist longevity, appeared to be on the verge of

renouncing its obligation under the Treaty for the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear

Weapons (or “NPT,” for “Non-Proliferation Treaty”) and developing its own nuclear

bomb. The short-term resolution to the difficulty involved North Korea’s pledge to

continue to adhere to the NPT and a pledge by the US, embodied in an international

agreement, to obtain for North Korea nuclear-power technology not readily useful in

constructing nuclear weapons.

CHAPTER TWO—A CASE STUDY: KOREA

59

SECTION ONE

The Korean War and the United Nations

Immediately below is a short reading about Korea in the first half of the

20 century. (It is followed by a much more detailed reading focused on the

Korean War itself.)

th

KOREAN HISTORY, 1910-1950

Microsoft Encarta ‘97 (bundled version)

Reproduced for Educational Purposes Only.

No Charge for Distribution.

From “Korea,” Microsoft® Encarta® 97 Encyclopedia.

© 1993-1996 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.

JAPANESE RULE (1910-45)

Japanese domination of Korea actually began with the Protectorate Treaty

(1905), forced on the country after the Russo-Japanese War, under which Japan

assumed control of Korea’s foreign relations and ultimately of its police and

military, currency and banking, communications, and all other vital functions.

These changes were tenaciously resisted by the Koreans, from King Kojong at the

top to guerrilla armies at the bottom. Formal annexation followed when it was

realized that the Koreans would never accept nominal sovereignty with actual

Japanese control. From 1910 to 1918 Japan solidified its rule by purging

60

INTERNATIONAL LAW IN CONTEXT

nationalists, gaining control of the land system, and enforcing rigid administrative

changes. In 1919 these measures, along with the general demand for national selfdetermination following World War I, led to what is known as the March First

Movement. Millions of Koreans took to the streets in nonviolent demonstrations

for independence, but foreign support was not forthcoming, Japanese power was

great, and the movement was suppressed. In the following years Japan tightened

its control, suppressing nationalist movements. Efforts aimed at assimilation,

including such draconic measures as the outlawing of the Korean language and

even of Korean family names, stopped only with Japan’s defeat in World War II.

POSTWAR PARTITION

Shortly before the end of the war in the Pacific, the U.S. and the USSR

agreed to divide Korea at the 38th parallel for the purpose of accepting the

surrender of Japanese troops. Both powers, however, used their presence to

promote friendly governments. The USSR suppressed the moderate nationalists in

the north and gave its support to Kim Il Sung, a Communist who had led antiJapanese guerrillas in Manchuria. In the south was a well-developed leftist

movement, opposed by various groups of right-wing nationalists. Unable to find a

congenial moderate who could bring these forces together, the U.S. ended up

suppressing the left and promoting Syngman Rhee, a nationalist who had opposed

the Japanese and had lived in exile in the U.S. All Koreans looked toward

unification, but in the developing cold war atmosphere, U.S.-Soviet unification

conferences (1946, 1947) broke up in mutual distrust. In 1947 both powers began

arranging separate governments. U.S.-sponsored elections in 1948, observed by

the United Nations, led to the founding of the Republic of Korea in August 1948.

The north followed in September 1948 by establishing the Democratic People’s

Republic of Korea (DPRK). On June 25, 1950, DPRK forces attacked across the

38th parallel, starting the Korean War.

CHAPTER TWO—A CASE STUDY: KOREA

61

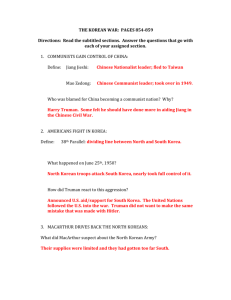

The reading that begins just after the map on the next page is excerpted

from a political scientist’s history of American foreign policy from 1938 to 1985.

{Its author, Stephen E. Ambrose, has mostly gone on to write view-from-thefoxhole combat histories of World War II in the European Theater of Operations,

such as D-Day June 6, 1944: The Climactic Battle of World War II and Citizen

Soldiers : The U.S. Army from the Normandy Beaches to the Bulge to the

Surrender of Germany, June 7, 1944-May 7, 1945 and, most recently, the doublecoloned The Victors: Eisenhower and His Boys: The Men of World War II. Those

with an interest in what Thomas Jefferson did between writing the Declaration of

Independence and founding the University of Virginia—I think he held some kind

of political office or something—might take note of Ambrose’s Undaunted

Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American

West.}

The reading below is intended to provide you with a general historical and

political introduction to the Korean War. Subsequent readings provide you with

some material more explicitly involving international and domestic law.

Immediately below, just before the reading, is a map from Encyclopedia

Americana that you may find useful.

62

INTERNATIONAL LAW IN CONTEXT

Map Goes Here

CHAPTER TWO—A CASE STUDY: KOREA

63

RISE TO GLOBALISM:

AMERICAN FOREIGN POLICY SINCE 1938

4th Revised Edition (1985)

by Stephen E. Ambrose

Reproduced for Educational Purposes Only.

Distributed at No Charge.

Copyright 1985 by Stephen E. Ambrose

CHAPTER SEVEN: KOREA

[The author begins the narrative with the situation in Asia in early 1950.]

... In China Mao’s armies were being deployed for an assault on Formosa,

where the remnants of Chiang’s forces had retreated. The United States had

stopped all aid to Chiang, thereby arousing the fury of the Republicans. Truman

was under intense pressure to resume the shipment of supplies to the Nationalist

Chinese. Former President Herbert Hoover joined with Senator Taft in demanding

that the U.S. Pacific Fleet be used to prevent an invasion of Formosa.

In Japan the United States was preparing to write a unilateral peace treaty

with that country, complete with agreements that would give the United States

military bases in Japan on a long-term basis. But in early 1950 the Japanese

Communist Party staged a series of violent demonstrations against American

military personnel in Tokyo. Even moderate Japanese politicians were wary of

granting base rights to the American forces. The U.S. Air Force was confronted

with the possibility of losing its closest airfields to eastern Russia.

64

INTERNATIONAL LAW IN CONTEXT

In Korea all was tension. Postwar Soviet-American efforts to unify the

country, where American troops had occupied the area south of the thirty-eighth

parallel and Russia the area to the north, had achieved nothing. In 1947 the United

States had submitted the Korean question to the UN General Assembly for

disposition. Russia refused to go along. Elections were held anyway in South

Korea in May 1948 under UN supervision. Syngman Rhee became President of

the Republic of Korea. The Russians set up a Communist puppet government in

North Korea. Both the United States and the Soviets withdrew their occupation

troops; both continued to give military aid to their respective sides, although the

Russians did so on a larger scale.

Rhee was a petty dictator and thus an embarrassment to the United States.

In April 1950 Acheson told Rhee flatly that he had to hold elections. Rhee

agreed, but his own party collected only 48 seats in the Assembly, with 120 going

to other parties, mostly on the Left. The new Assembly immediately began to

press for unification, even if on North Korean terms. Rhee was on the verge of

losing control of his government. On June 25, North Korean troops crossed the

thirty-eighth parallel in force. ...

Truman was ready with his countermeasures. Within hours of the attack he

ordered MacArthur to send supplies to the South Koreans. He also sent the U.S.

Seventh Fleet to the Formosan Straits to prevent a possible Chinese invasion of

Formosa, and he promised additional assistance to counter revolutionary forces in

the Philippines and Indochina.

These were sweeping policy decisions. Using the Seventh Fleet to protect

Formosa constituted a complete reversal of policy with respect to the Chinese

civil war. Having MacArthur ship supplies to Rhee’s troops carried with it the

implication that the United States would defend South Korea. Among other

things, the decision carried with it the possibility of the introduction of American

troops into the battle, for it was already doubtful that the South Koreans would be

able to hold out alone.

Since 1941 the United States had pursued a military policy of avoiding

ground warfare on mainland Asia. When the country pulled out of Korea in 1948

there were no American troops stationed anywhere on the Continent. Truman was

on the verge of changing the policy and extending American military power to the

Asian mainland.

CHAPTER TWO—A CASE STUDY: KOREA

65

On June 25, the day the attack began, the United States launched a massive

diplomatic counterattack. In the Security Council she pushed through a resolution

branding the North Koreans as aggressors, demanding a cessation of hostilities,

and requesting a withdrawal behind the thirty-eighth parallel. The resolution’s

sweeping nature gave the United States the advantage of United Nations approval

and support for military action in Korea. This was the first time ever that an

international organization had actually taken concrete steps to halt and punish

aggression (Russia failed to veto the resolution because she was boycotting the

United Nations at the time because it refused to give Chiang’s seat on the Security

Council to Mao), and it lifted spirits throughout the country. Despite the UN

involvement, however, the overwhelming bulk of equipment used in Korea and

the overwhelming number of non-Korean fighting men came from the United

States. ...

... Truman announced that he had “ordered United States air and sea forces

to give the Korean Government troops cover and support.” His Air Force advisers

had convinced him that America’s bombers would be able to stop the aggression

in Korea by destroying the Communist supply lines. ...

... Much of this was wishful thinking. It was partly based on the American

Air Force’s strategic doctrine and its misreading of the lessons of air power in

World War II, partly on the racist attitude that Asians could not stand up to

Western guns, and partly on the widespread notion that Communist governments

had no genuine support. Lacking popularity, the Communists would be afraid to

commit their troops to battle, and if they did, the troops would not fight.

The question of who would fight and who would not was quickly

answered. The North Koreans drove the South Koreans down the peninsula in a

headlong retreat. American bombing missions slowed the aggressors not at all.

The South Koreans fell back in such a panic that two days after Truman sent in

the Air Force he was faced with another major decision: He would either have to

send in American troops to save the position, which meant accepting a much

higher cost for the war than he had bargained for, or else face the loss of all

Korea, at a time when the Republicans were screaming, “Who lost China?”

66

INTERNATIONAL LAW IN CONTEXT

On June 30 Truman ordered United States troops stationed in Japan to

proceed to Korea. America was now at war on the mainland. The President

promised that more troops would soon be on their way from the United States. In

an attempt to keep the war and its cost limited, he emphasized that the United

States aimed only “to restore peace and ... the border.” At the United Nations the

Americans announced that their purpose was the simple one of restoring the

thirty-eighth parallel as the dividing line. The policy, in other words, was

containment, not rollback.

It had been arrived at unilaterally, for Truman had not consulted his

European or Asian allies before acting, not to mention Congress. … Once again,

as in F.D.R.’s war on the Atlantic in the summer of 1941, the United States found

itself at war without the Constitutionally required congressional declaration of

war.

In Korea, American reinforcements arrived just in time, and together with

the South Koreans they held on in the Pusan bridgehead through June and July.

By the beginning of August it was clear that MacArthur would not be forced out

of Korea and that when MacArthur’s troops broke out of the perimeter they would

be able to destroy the North Korean Army. ...

... On September 15 MacArthur successfully outflanked the North Koreans

with an amphibious landing at Inchon, far up the Korean peninsula. In a little

more than a week MacArthur’s troops were in the capital, Seoul, and they had cut

off the bulk of the North Korean forces around Pusan. On September 27 the Joint

Chiefs ordered MacArthur to destroy the enemy army and authorized him to

conduct military operations north of the thirty-eighth parallel. On October 7

American troops crossed the parallel. The same day the United Nations approved

(47 to 5) an American resolution endorsing the action. ...

The Chinese issued a series of warnings, culminating with a statement to India

for transmission to the United States, that China would not “sit back with folded

hands and let the Americans come to the border.” When even this was discounted, the

CHAPTER TWO—A CASE STUDY: KOREA

67

Chinese publicly stated on October l0 that if the Americans continued north, they

would enter the conflict. The Russians were more cautious, but when on October 9

some American jet aircraft strafed a Soviet airfield only a few miles from

Vladivostok, they sent a strong protest to Washington. Truman immediately decided

to fly to the Pacific to see MacArthur and make sure he restrained the Air Force.

Fighting Chinese forces in Korea was one thing, war with Russia another. The

Americans were willing to try to liberate Pyongyang, but they were not ready to

liberate Moscow.

The Truman-MacArthur meeting at Wake Island in October accomplished its

main purpose, for the Air Force thereafter confined its activities to the Korean

peninsula. More important was what it revealed. Commentators have concentrated

almost exclusively on MacArthur’s statement that the Chinese would not dare enter

the war. On this point everybody, not just MacArthur, was wrong. ...

...[T]he Chinese had not been seen nor were they expected in Korea.

MacArthur flew back to Tokyo to direct the last offensive. By October 25 his forces

reached the Yalu at Chosan. That day Chinese “volunteers” struck South Korean and

American troops around the Choshin Reservoir. After hard fighting MacArthur’s units

fell back. The Chinese then retired. They had, by their actions, transmitted two

messages: (I) they would not allow MacArthur’s forces to proceed unmolested to the

Yalu, and (2) their main concern continued to be Formosa, and like Truman they

wanted to limit the fighting in Korea. The second message was reinforced by Peking’s

acceptance of an invitation to come to the United Nations to discuss the Formosa

situation and, hopefully, the Korean War. ...

MacArthur planned to launch another ground offensive on November 15,

which would have coincided with the announced date of arrival of the Chinese

delegates at the United Nations. The delegates, however, were delayed. On November

11 MacArthur learned of the delay, and later that the Chinese delegation would arrive

at the United Nations on November 24. MacArthur put off his offensive, finally

beginning it on the morning of November 24. Thus the headlines that greeted the

Chinese delegates when they arrived at the United Nations declared that MacArthur

promised to have the boys “home by Christmas,” after they had all been to the Yalu.

The Americans were once again marching to the Chinese border, this time in greater

force.

Europeans were incensed. The French government charged that

MacArthur had “launched his offensive at this time to wreck the negotiations” and

the British New Statesman declared that MacArthur had “acted in defiance of all

common sense, and in such a way as to provoke the most peace-loving nation.”

68

INTERNATIONAL LAW IN CONTEXT

The Chinese delegation at the United Nations soon packed its bags and returned to

Peking, taking with it only what it had brought plus some additional bitterness.

The failure of the negotiations did not upset Truman, but the failure of the

offensive did. MacArthur had advanced on two widely separated routes, with his

middle wide open. How he could have done so, given the earlier Chinese

intervention, remains a mystery to military analysts. The Chinese poured

thousands of troops into the gap and soon sent MacArthur’s men fleeing for their

lives. In two weeks the Chinese cleared much of North Korea, isolated

MacArthur’s units into three bridgeheads, and completely reversed the military

situation.

The Americans, who had walked into the disaster together, split badly on

the question of how to get out. MacArthur said he now faced “an entirely new

war” and indicated that the only solution was to strike at China itself. But war

against China might well mean war against Russia, which Truman was not

prepared to accept. Instead, the administration decided to return to the pre-Inchon

policy of restoring the status quo ante bellum in Korea while building NATO

strength in Europe. All talk of liberating iron curtain capitals disappeared. Never

again would the United States attempt by force of arms to free a Communist state.

A lesson had been learned, but not fully accepted immediately, and it was

enormously frustrating. Just how frustrating became clear on November 30, when

at a press conference Truman called for a worldwide mobilization against

Communism and, in response to a question, declared that if military action against

China was authorized by the United Nations, MacArthur might be empowered to

use the atomic bomb at his discretion. Truman casually added that there had

always been active consideration of the bomb’s use, for after all it was one of

America’s military weapons.

Much alarmed, British Prime Minister Atlee flew to Washington, fearful

that Truman really would use the bomb [but Truman eventually] assured Atlee

that every effort would be made to stay in Korea and then promised that as long as

MacArthur held on[,] there would be no bombs dropped.

... Truman put the nation on a Cold War footing. He got emergency

powers from Congress to expedite war mobilization, reintroduced selective

service, submitted a $50-billion defense budget ..., sent two more divisions (a total

of six) to Europe, doubled the number of air groups to ninety-five, obtained new

CHAPTER TWO—A CASE STUDY: KOREA

69

bases in Morocco, Libya, and Saudi Arabia, increased the Army by 50 percent to

3.5 million men, pushed forward the Japanese peace treaty, stepped up aid to the

French in Vietnam, initiated the process of adding Greece and Turkey to NATO,

and began discussions with Franco that led to American aid to Fascist Spain in

return for military bases there.

Truman’s accomplishments were breathtaking. He had given the United

States a thermonuclear bomb (March 1951) and rearmed Germany. He pushed

through a peace treaty with Japan (signed in September 1951) that excluded the

Russians and gave the Americans military bases, allowed for Japanese

rearmament and unlimited industrialization, and encouraged a Japanese boom by

dismissing British, Australian, Chinese; and other demands for reparations.

Truman extended American bases around the world, hemming in both Russia and

China. He had learned, in November of 1950, not to push beyond the iron and

bamboo curtains, but he had made sure that if any Communist showed his head on

the free side of the line, someone—usually an American—would be there to shoot

him. ...

... In January and February 1951 MacArthur resumed the offensive and

drove the Chinese and North Koreans back. By March he was again at the thirtyeighth parallel. The administration, having been burned once, was ready to

negotiate. MacArthur sabotaged the efforts to obtain a cease-fire by crossing the

parallel and by demanding an unconditional surrender from the Chinese. Truman

was furious. He decided to remove the General at the first opportunity.

It came shortly. On April 5 Representative Joseph W. Martin, Jr.,

Republican, read to the House a letter from MacArthur calling for a new foreign

policy. The General wanted to reunify Korea, unleash Chiang for an attack on the

mainland, and fight Communism in Asia rather than in Europe. “Here in Asia,” he

said, “is where the communist conspirators have elected to make their play for

global conquest. Here we fight Europe’s war with arms while the diplomats there

still fight it with words.”

Aside from the problem of a soldier challenging Presidential supremacy by

trying to get foreign policy, the debate centered on Europe-first versus Asia-first.

...

70

INTERNATIONAL LAW IN CONTEXT

After Truman relieved him MacArthur returned to the United States to

receive a welcome that would have made Caesar envious. Public opinion polls

showed that three out of every four Americans disapproved of the way

Truman was conducting the war. ...

[Despite US reticence, the] pressure from the United Nations and the

NATO allies to negotiate could not be totally ignored, ... and on July 10, 1951,

peace talks—without a cease-fire—began. They broke down on July 12. For the

remainder of the year, they were on again, off again. The front lines began to

stabilize around the thirty-eighth parallel while American casualties dropped to an

“acceptable” weekly total. The war, and rearmanent, continued.

CHAPTER TWO—A CASE STUDY: KOREA

71

QUESTION

For Ambrose, what determines the course of history? Politics? Personality?

Ideas? The earlier course of history? International law? Domestic law?

72

INTERNATIONAL LAW IN CONTEXT

Below are some excerpts from the UN Charter that are especially relevant

to the international legal aspects of the Korean War.

CHARTER OF THE UNITED NATIONS

Signed at San Francisco on 26 June 1945.

Entered into force on 24 October 1945.

Current version (as amended).

Reproduced for Educational Purposes Only.

Distributed at No Charge.

This document is available at the UN Web site (www.un.org); the United Nations

does not appear to claim a copyright with respect to its publications.

Article 2

…

4. All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat

or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any

state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations.

Article 51

Nothing in the present Charter shall impair the inherent right of individual

or collective self-defense if an armed attack occurs against a Member of the

United Nations, until the Security Council has taken measures necessary to

maintain international peace and security. …

CHAPTER V:

CHAPTER TWO—A CASE STUDY: KOREA

73

THE SECURITY COUNCIL

Article 23

1. The Security Council shall consist of fifteen Members of the United

Nations. The People’s Republic of China, France, the [Russian Federation], the

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, and the United States of

America shall be permanent members of the Security Council. The General

Assembly shall elect ten other Members of the United Nations to be nonpermanent members of the Security Council …

Article 27

1. Each member of the Security Council shall have one vote.

2. Decisions of the Security Council on procedural matters shall be made

by an affirmative vote of nine members.

3. Decisions of the Security Council on all other matters shall be made by

an affirmative vote of nine members including the concurring votes of the

permanent members ….

CHAPTER VII:

ACTION WITH RESPECT TO THREATS TO THE PEACE,

BREACHES OF THE PEACE, AND ACTS OF AGGRESSION

Article 39

The Security Council shall determine the existence of any threat to the

peace, breach of the peace, or act of aggression and shall make recommendations,

or decide what measures shall be taken in accordance with Articles 41 and 42, to

maintain or restore international peace and security.

74

INTERNATIONAL LAW IN CONTEXT

Article 41

The Security Council may decide what measures not involving the use of

armed force are to be employed to give effect to its decisions ….

Article 42

Should the Security Council consider that measures provided for in Article

41 would be inadequate or have proved to be inadequate, it may take such action

by air, sea, or land forces as may be necessary to maintain or restore international

peace and security. Such action may include demonstrations, blockade, and other

operations by air, sea, or land forces of Members of the United Nations.

Article 48

1. The action required to carry out the decisions of the Security Council for

the maintenance of international peace and security shall be taken by all the

Members of the United Nations or by some of them, as the Security Council may

determine.

2. Such decisions shall be carried out by the Members of the United

Nations directly and through their action in the appropriate international agencies

of which they are members.

FROM the UN Web Site at

http://www.un.org/Depts/Treaty/final/ts2/newfiles/part_boo/i_boo/i_1.html

CHAPTER TWO—A CASE STUDY: KOREA

75

SOME UN SECURITY COUNCIL RESOLUTIONS

RELATING TO KOREA

Reproduced for Educational Purposes Only.

Distributed at No Charge.

The UN does not appear to claim a copyright with respect to its publications.

UN SECURITY COUNCIL RESOLUTION 82

Resolution of 25 June 1950 [S/1501]

COMPLAINT OF AGGRESSION UPON THE REPUBLIC OF KOREA

The Security Council,

Recalling the finding of the General Assembly in its resolution 293 (IV) of

21 October 1949 that the Government of the Republic of Korea is a lawfully

established government having effective control and jurisdiction over that part of

Korea where the United Nations Temporary Commission on Korea was able to

observe and consult and in which the great majority of the people of Korea reside;

that this Government is based on elections which were a valid expression of the

free will of the electorate of that part of Korea and which were observed by the

Temporary Commission; and that this is the only such Government in Korea, …

Noting with grave concern the armed attack on the Republic of Korea by

forces from North Korea,

Determines that this action constitutes a breach of the peace; and

76

INTERNATIONAL LAW IN CONTEXT

I

Calls for the immediate cessation of hostilities;

Calls upon the authorities in North Korea to withdraw forthwith their

armed forces to the 38th parallel;

Calls upon all Member States to render every assistance to the United

Nations in the execution of this resolution and to refrain from giving assistance to

the North Korean authorities.

—Adopted at the 473rd meeting by 9 votes to none, with one abstention

(Yugoslavia). One member (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics) was absent.

[Some notes on the last line above:]

[Originally, article 23 of the Charter specified 11 members in the Security

Council, not the current version’s 15. Article 27(2) and 27(3) referred to 7 votes,

not the current version’s 9.]

[The growth in membership on the Security Council has been entirely in

non-permanent members. There were five permanent members in 1950, just as

there are now. Three of those five permanent members are exactly the same now

as in 1950: France, Great Britain, and the United States. Two, however, are at

least nominally different. The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (“Soviet

Union”) then held the seat now held by the Russian Federation. The Republic of

China (with its operational capital in Taipei on the island of Formosa, a.k.a.

Taiwan) then held the seat now held by the People’s Republic of China (with its

capital in Beijing).]

[The absence of the Soviet Union from the meeting resulting in the

Resolution above was deliberate. The Soviet Union was protesting the decision

by the United Nations to seat the Republic of China in the UN (and on its Security

Council) rather than seating the People’s Republic of China.]

CHAPTER TWO—A CASE STUDY: KOREA

77

QUESTIONS ABOUT RESOLUTION 82

(1) Take another look at Article 2(4) of the Charter on page 71. Based on

the Ambrose reading, would you say that, as of June 25, 1950, South Korea faced

a “threat or use of force against [its] territorial integrity or political integrity”

mentioned in Article 2(4) of the Charter?

(2) Suppose that you were a lawyer working in the US Department of State

in 1950, and you were asked to advise President Truman as to whether Resolution

82 had a substantive legal basis in the UN Charter. What would you say?

78

INTERNATIONAL LAW IN CONTEXT

QUESTIONS ABOUT RESOLUTION 82

(continued)

(3) Does your answer to question (2) above change depending on whether

North Korea and/or South Korea was a member of the UN in 1950? (In fact,

neither was a member of the UN until 1991.)

(4) Why might President Truman care about whether Resolution 82 had a

legal basis in the UN Charter? Why might he not care?

CHAPTER TWO—A CASE STUDY: KOREA

79

QUESTIONS ABOUT RESOLUTION 82

(concluded)

(5) What do you think would have happened if the Soviet Union had

attended the 473rd meeting of the Security Council? Do you base your answer on

political or legal factors?

(6) Look back at Article 27 of the Charter on page 72. If you represented

the Soviet Union, what argument could you make from the simple absence of the

Soviet Union from the meeting?

80

INTERNATIONAL LAW IN CONTEXT

UN SECURITY COUNCIL RESOLUTION 83

Resolution of 27 June 1950 [S/1511]

The Security Council, ...

Having noted from the report of the United Nations Commission on Korea

[citation to UN document omitted] that the authorities in North Korea have

neither ceased hostilities nor withdrawn their armed forces to the 38th parallel,

and that urgent military measures are required to restore international peace and

security,

Having noted the appeal from the Republic of Korea to the United Nations

for immediate and effective steps to secure peace and security,

Recommends that the Members of the United Nations furnish such

assistance to the Republic of Korea as may be necessary to repel the armed attack

and to restore international peace and security in the area.

—Adopted at the 474th meeting by 7 votes to 1 (Yugoslavia). Two

members (Egypt and India) did not participate in the voting; one member (Union

of Soviet Socialist Republics) was absent.

QUESTION ABOUT RESOLUTION 83

What new obligations in international law does this resolution create?

CHAPTER TWO—A CASE STUDY: KOREA

81

UN SECURITY COUNCIL RESOLUTION 84

Resolution of 7 July 1950 [S/1588]

The Security Council, ...

1. Welcomes the prompt and vigorous support which Governments and

peoples of the United Nations have given to its resolutions 82 (1950) and 83

(1950) of 25 and 27 June 1950 to assist the Republic of Korea in defending itself

against armed attack and thus to restore international peace and security in the

area;

2. Notes that Members of the United Nations have transmitted to the

United Nations offers of assistance for the Republic of Korea;

3. Recommends that all Members providing military forces and other

assistance pursuant to the aforesaid Security Council resolutions make such forces

and other assistance available to the unified command under the United States of

America;

4. Requests the United States to designate the Commander of such forces;

5. Authorizes the unified command at its discretion to use the United

Nations flag in the course of operations against North Korean forces concurrently

with the flags of the various nations participating;

6. Requests the United States to provide the Security Council with reports

as appropriate on the course of action taken under the unified command.

—Adopted at the 476th meeting by 7 votes to none, with 3 abstentions

(Egypt, India, Yugoslavia). One member (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics)

was absent.

82

INTERNATIONAL LAW IN CONTEXT

QUESTION ABOUT RESOLUTION 84

What new obligations in international law does this resolution create?

CHAPTER TWO—A CASE STUDY: KOREA

83

UN SECURITY COUNCIL RESOLUTION 88

Resolution of 8 November 1950 [S/1892]

The Security Council, ...

Decides to invite, in accordance with rule 39 of the provisional rules of

procedure, a representative of the Central People’s Government of the People’s

Republic of China to be present during discussion by the Council of the special

report of the United Nations Command in Korea. [footnote omitted]

—Adopted at the 520th meeting by 8 votes to 2 (China, Cuba), with 1

abstention (Egypt)

QUESTION ABOUT RESOLUTION 88

Look back at Article 23 of the Charter on page 57. Given that China voted

against this measure, how must one characterize Resolution 88 in order for it to

have passed the Security Council?

84

INTERNATIONAL LAW IN CONTEXT

UN SECURITY COUNCIL RESOLUTION 90

Resolution of 31 January 1951 [S/1995]

The Security Council,

Resolves to remove the item “Complaint of Aggression upon the Republic

of Korea’ from the list of matters of which the Council is seized.

—Adopted unanimously at the 531st meeting.

QUESTION ABOUT RESOLUTION 90

Note that the Soviet Union was present at the meetings leading to

Resolutions 89 and 90. Note furthermore that the Soviet Union and the United

States both voted in favor of both resolutions, even though the United States and

the Soviet Union were bitter rivals in 1951. The vote on Resolution 90 is

unanimous—indeed, the only Resolution in this series without any no-votes or

absences or abstentions or non-participations in the voting. Does that mean that

Resolution 90 is trivial?