WHOLE PERSON HEALTH CARE

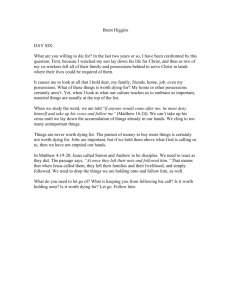

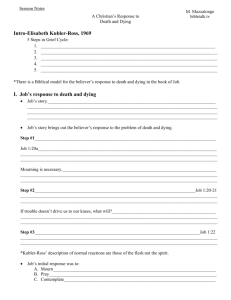

advertisement