♦ The Evolution of Optical Systems: Optics Everywhere

advertisement

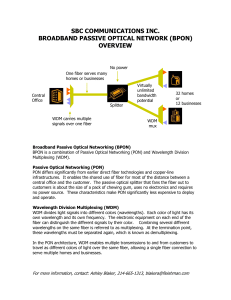

♦ The Evolution of Optical Systems: Optics Everywhere Rod C. Alferness, Herwig Kogelnik, and Thomas H. Wood With the explosion of capacity demands driven by the Internet, optical networking systems are experiencing tremendous growth and are providing increasingly high transmission capacities. As importantly, with the advent of the optical amplifier and wavelength division multiplexing (WDM), optics is playing a larger role in networking and is extending further to the edge of the network. Once limited to long-haul point-to-point systems, Lucent Technologies is now commercializing multipoint metro WDM ring systems that include software-controlled optical wavelength add/drop multiplexers and soon will offer large optical cross connects. These optical network elements, together with network management software, will enable rapid provisioning of wavelength services, as well as rapid network restoration. In addition, as the cost of optics is driven down and the demand for bandwidth to businesses and residential customers continues to grow, optical systems are extending out from the network core and metro to access applications. The confluence of a proliferation of broadband service applications and rapidly maturing optical technology are literally driving optical systems into all segments. Increasingly, optics is literally everywhere. Introduction Early lightwave systems were intended primarily for long-haul, uninterrupted optical transport between distant points. The recent introduction of wavelength division multiplexing (WDM) for capacity expansion of point-to-point links has opened the way for evolution to optical layer networks. In these networks, optical channels (defined on an optical fiber by their wavelengths) provide the bandwidth units by which multi-node transmission networks can be built. Such networks, which require sophisticated optical network elements that in turn require highly functional optical components, including optical switching fabrics, are now part of products or product plans of Lucent Technologies’ Optical Networking Group. Beyond backbone and metro transport optical networks, the evolution of optics into access networks and enterprise local area networks (LANs) appears highly viable. Researchers and engineers at Bell Labs have 188 Bell Labs Technical Journal ◆ January–March 2000 played a critical role in the explosion and proliferation of optics over the last 25 years. In this paper, we provide a brief overview of the evolving and expanding role of optics in communication systems. We first discuss the growth of point-to-point transmission systems, then follow with the evolution of WDM transport networks, and finish with a view of access and LAN systems. The advances in optical systems and higher-level network capabilities that provide our focus have depended strongly on advances in optical components and optical fiber technology. These related topics are summarized in companion papers by Brinkman et al.1 and Glass et al.2 High-Capacity Transmission Systems The explosive growth of optical fiber transmission technology parallels that of computer processing and other key information technologies. These technolo- Copyright 2000. Lucent Technologies Inc. All rights reserved. gies are combining to meet the burgeoning global demand for new information services including data, Internet, and broadband services. Indeed, their rapid advance has helped fuel this demand. Lightwave technology is now advancing at a rate exceeding a factor of 100 every ten years. This is evident from Figure 1, which depicts the transmission capacity achieved per fiber as a function of year for the last 20 years. Two trend lines are shown: one for commercial systems and one for system prototypes demonstrated in research laboratories. Note the logarithmic scale on the vertical axis showing capacity in bits per second. As in other information technologies, “giga” (109) performance has been improving to “tera” (1012) performance over a course of 15 years. Long distance transmission entered the “tera era” experimentally in 1996, when three research laboratories reported transmission capacities of 1 Tb/s per fiber (discussed further below). To appreciate this staggering transmission capacity, recall that a fiber is just a thin strand of glass with a diameter comparable to that of a human hair, and a terabit is, of course, a million megabits. At the terabit-per-second rate, this implies that one hair-thin fiber can support about 40 million data connections at 28 kb/s, 20 million digital voice telephony channels, or a half million compressed digital television channels. To gain further perspective on the advances of lightwave technology, recall the digital transmission technologies that it replaces: twisted pair and coaxial cable systems. Compared to these, fiber technology offers economic advantages beyond increased capacity, such as the small size and weight of fiber-optic cables and the large spacing of optoelectronic regenerators. The first digital transmission technology in the United States was the T1 carrier system introduced in 1962. It carried 24 digital voice channels over a twisted pair of copper wires at a transmission rate of about 1.5 Mb/s. The regenerator spacing of T1 systems was about 2 km (6000 feet). The most advanced digital coaxial cable transmission system introduced in the early 1980s was the T4M system. It used a 0.375-in–diameter coaxial cable and transmitted at a rate of 274 Mb/s with a regenerator spacing of 1.6 km (1 mile). In contrast, the regenerator spans of commercial fiber-based systems Panel 1. Abbreviations, Acronyms, and Terms ATM—asynchronous transfer mode CATV—cable television CPON—composite PON CSMA/CD—carrier-sense multiple access/collision detection CWDM—coarse WDM DARPA—Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency DFB—distributed feedback DLC—digital loop carrier DS—dispersion shifted DSL—digital subscriber line DWDM—dense WDM EDFA—erbium-doped fiber amplifier EMI—electromagnetic interference ETDM—electronic time division multiplexing FSAN—Full Service Access Network FTTC—fiber to the curb FTTH—fiber to the home HFC—hybrid fiber-coax IC—integrated circuit InP—indium phosphide LAN—local area network MONET—Multi-Wavelength Optical Networking NGLN—Next-Generation Lightwave Network NTT—Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Corporation OC-N—optical carrier digital signal rate of N 3 51.840 Mb/s in a SONET system ONU—optical network unit PON—passive optical network QAM—quadrature amplitude modulation RF—radio frequency SDH—synchronous digital hierarchy SM—single mode SONET—synchronous optical network T1—terrestrial (North American) facility for transporting signals at the primary rate of 1.544 Mb/s (24 64-kb/s channels) TDMA—time division multiple access TDM—time division multiplexing VCSEL—vertical-cavity surface-emitting laser WDM—wavelength division multiplexing are typically at least 50 km and reach to several hundred kilometers, as shown in Table I, an expansion of an earlier published table.3 The dramatic increase in lightwave system capacity has had a strong impact on lowering the cost of Bell Labs Technical Journal ◆ January–March 2000 189 1014 1013 Capacity per fiber (b/s) 1012 1011 1010 109 108 19 78 19 80 19 82 19 84 19 86 19 88 19 90 19 92 19 94 19 96 19 98 20 00 107 Year Experimental Single channel (ETDM) Single channel (OTDM) Multi-channel (WDM) WDM + OTDM WDM + POL WDM + OTDM WDM Commercial Single channel (ETDM) Multi-channel (WDM) ETDM – Electronic time division multiplexing OTDM – Optical time division multiplexing POL – Polarization division multiplexing WDM – Wavelength division multiplexing Figure 1. Progress in lightwave transmission capacity. long distance transmission. The Dixon-Clapp rule projects that the cost per voice channel reduces with the square root of the systems capacity. Using this, we estimate from Figure 1 that the technology cost of trans- 190 Bell Labs Technical Journal ◆ January–March 2000 mitting one voice channel is decreasing by a factor of 10 every ten years. Consequently, distance is playing a smaller and smaller role in the equation of telecom economics. An Internet user, for example, will click a Table I. Generations of terrestrial lightwave technologies. Year Fiber type Wavelength WDM channels Bit rate/ channel Bit rate/ fiber FT3 1980 MM 0.82 µm 1 45 Mb/s 45 Mb/s 672 7 km FT3C 1983 MM 0.82 µm 1 90 Mb/s 90 Mb/s 1,344 7 km FTG-417 1985 SM 1.3 µm 1 417 Mb/s 417 Mb/s 6,048 50 km FTG-1.7 1987 SM 1.3 µm 1 1.7 Gb/s 1.7 Gb/s 24,192 50 km FTG-1.7 WDM 1989 SM 1.3/1.55 µm 2 1.7 Gb/s 3.4 Gb/s 48,384 50 km FT-2000 1992 SM 1.3 µm 1 2.5 Gb/s 2.5 Gb/s 32,256 50 km — SM 1.3/1.55 µm 2 2.5 Gb/s 5 Gb/s 64,120 50 km NGLN 1995 SM 1.55 µm 8 2.5 Gb/s 20 Gb/s 258,000 360 km NGLN II 1997 SM 1.55 µm 16 2.5 Gb/s 40 Gb/s 516,000 360 km WaveStar™ 400G 1999 SM 1.55 µm 80 40 2.5 Gb/s 10 Gb/s 200 Gb/s 400 Gb/s 2,580,000 5,160,000 640 km 640 km System FT-2000 WDM Voice channels per fiber Regenerator spans MM – Multimode NGLN – Next-Generation Lightwave Network SM – Single mode WDM – Wavelength division multiplexed Web site regardless of its geographical distance. This new paradigm was eloquently described in a recent telecom advertisement in the United Kingdom: “Geography is History.” Let us now examine some milestones in optical systems that underpin the progress recorded in Figure 1 and Table I. Consider first the data near the lower left corner of the figure. The lowest refers to the FT3 lightwave technology introduced by the Bell System in 1980.4 It had a digital transmission rate of 45 Mb/s and a regenerator spacing of 7 km. Multimode fibers were used and were operated at a wavelength of 0.82 µm. The light sources were gallium-arsenide–based semiconductor lasers. A speed upgrade of this technology, the FT3C system, carried 90 Mb/s per fiber. It was deployed in the first major lightwave installation of the United States—the Northeast Corridor system, linking Washington, D.C., with New York in 1983 and New York with Boston in 1984.3 A major shift of lightwave technology occurred immediately after the initial Northeast Corridor deployment. Research and development had prepared the enabling component technologies for this breakthrough:1,2 The new lightwave generation used single- mode (SM) fibers for higher capacity and switched the operating wavelength to 1.3 µm and then to both 1.3 and 1.55 µm where the “low-loss” and “minimumloss” fiber windows occur. SM lasers were required to match to the SM fibers; these had to be based on indium phosphide (InP) substrates to deliver the new wavelengths required. The FT Series G systems of 1985 operated at data rates of 417 Mb/s and then 1.7 Gb/s, and the lower loss allowed regenerator spacings of 50 km.3 Now let us switch our attention to the upper trend line in Figure 1 showing the lightwave prototype system experiments demonstrated in research labs worldwide. The entries shown represent demonstrations that were world records at the time; the research community calls them “hero experiments.” Many of the entries represent Bell Labs accomplishments. First, we focus our attention on the experiments indicated by solid circles. These demonstrated increases in fiber capacity by using high-speed electronic time division multiplexing (ETDM) and the new SM fiber technology operating at 1.55 µm to achieve large regenerator spans. For this set of data, increases in gigabit-per-second rates were accomplished by further advances in the enabling technologies, including Bell Labs Technical Journal ◆ January–March 2000 191 dispersion-shifted (DS) fibers, dispersion compensation (in the later high-speed experiments), distributedfeedback (DFB) lasers providing spectral control, highspeed modulation, sensitive high-speed receivers, and high-speed electronics. One example of these highspeed systems is the 1986 demonstration of 8 Gb/s transmission over 68 km of SM fiber.5 In time, these system experiments were pushed to 10 Gb/s, 20 Gb/s, and, recently, 40 Gb/s. The trend for the solid circles indicates that the single-channel bit rate of advanced high-speed systems increases by about a factor of 10 within ten years. The major factor limiting this advance has been the availability of high-speed electronics and high-speed integrated circuits (ICs). Recognition of this limitation led to yet another revolution in lightwave technology: wavelength division multiplexing. Computers have a problem similar to that of lightwave systems: their processing power—pulled by demand and pushed by advances in technology— increases by a factor of 100 or more every ten years, while the raw speed of the ICs that computers are based on increases by only a factor of 10 or so. The answer of computer designers has been the use of parallel architectures. The answer of the designers of advanced lightwave systems is similar: the use of many parallel high-speed channels carried by different wavelengths. This is called wavelength division multiplexing (WDM). The use of WDM provides other advantages, such as the tolerance that WDM systems have of the high dispersion present in the low-loss window of embedded fibers. Together with newly developed erbium-doped fiber amplifiers (EDFAs), WDM systems have been responsible for yet another revolutionary generation of lightwave systems, creating the “knee” in the upper (research) trend line of Figure 1. This latest generation has not only led to a dramatic increase in fiber capacity but has enabled very large regenerator spacings (up to 10,000 km in undersea systems) and has opened a new dimension in networking: it added the dimension of wavelength to the earlier dimensions of space and time. WDM required the development of new enabling technologies, including high-gain broadband optical amplifiers, guided-wave wavelength filters and multi- 192 Bell Labs Technical Journal ◆ January–March 2000 plexers, and WDM laser sources. It also required new systems and fiber concepts to counteract nonlinear effects caused by the large optical power arising from the presence of many channels in the fiber. Dispersionmanagement techniques were invented for this purpose, using system designs that avoid zero dispersion locally but provide near-zero dispersion globally. New “non-zero dispersion” fiber types were conceived for the same purpose. An early large-scale demonstration of the capability of WDM systems was the Roaring Creek Field Trial6,7 (not shown in Figure 1), which was begun in 1989 and completed in 1991. It demonstrated transmission of four WDM channels at data rates of 1.7 Gb/s per channel over a system span of 840 km. Thirteen EDFAs were used with a 70-km spacing between them. A concurrent research experiment at Bell Labs demonstrated transmission over eight channels at 2.5 Gb/s per channel. This was soon followed by a 1993 hero experiment showing transmission of eight WDM channels, each operating at 10 Gb/s over a 280-km span of dispersion-managed fiber.8 The bit error rate achieved in this 80-Gb/s experiment was less than 10-13. The entry for this experiment in Figure 1 is the triangle at the knee of the upper trend line. After 1993, rapid increases occurred in capacity improvements of research systems, and we soon witnessed the first large-scale deployment of a commercial WDM system. This was the deployment of the NGLN system, begun in 1995, in the long distance network of AT&T. Following the 1993 research experiments, a rapid sequence of experiments worldwide has demonstrated larger and larger capacities per fiber, and this trend is still continuing.9–11 Note, for example, the 1994 experiment where 17 WDM channels, each having a data rate of 20 Gb/s, were transmitted over 150 km of dispersion managed fiber. In early 1996, three simultaneous announcements reported breaking the terabit-per-second barrier, launching lightwave transmission technology into the “tera era.” These breakthroughs were demonstrated by researchers at Fujitsu,12 Bell Labs,13 and NTT.14 It is interesting to note the differences among the three approaches, which all used WDM techniques. Fujitsu used 150 km of conventional SM fiber with dispersion compensation and demonstrated transmission of 55 WDM channels with data rates of 20 Gb/s each. Bell Labs used 55 km of non-zero-dispersion fiber and transmitted 25 WDM channels that were polarization multiplexed to 50 independent channels with data rates of 20 Gb/s each. NTT used 40 km of DS fiber and transmitted 10 WDM channels at data rates of 100 Gb/s each. The latter data rates were obtained by optical time division multiplexing. Concluding our discussion of long distance transmission, we should add two remarks that relate to fiber nonlinearities. The first has to do with soliton transmission technology. Solitons are short pulses in which fiber dispersion and fiber nonlinearities are balanced to maintain short pulse widths over very long distances. Experimental soliton systems have set several world records on another economic measure, the bit-rate 3 distance product, which is a measure for the number of regenerators required for a given transmission task. That is, the higher the bit rate and the longer the distance between regenerators, the fewer the number of fibers and regenerators that are needed. This measure is particularly important for transoceanic systems, which have spans up to 10,000 km. Solitons, therefore, promise lower cost for future advanced ultra-long distance transmission systems. The second remark concerns the ultimate limit to the capacity growth shown in Figure 1. We now know that the loss window in silica fibers can be extended to a maximum bandwidth of about 50 THz.1 Current systems use binary amplitude modulation and achieve spectral efficiencies up to about 0.4 b/s/Hz, which would theoretically provide transmission rates of 20 Tb/s per fiber if the entire low-loss window were utilized. Shannon’s theorem15 tells us that spectral efficiency can be increased at the expense of increased signal power. For example, multilevel quadratureamplitude-modulation (QAM) systems that are used in other lower-bit-rate technologies (for example, wireless) achieve spectral efficiencies of about 4 b/s/Hz. In principle, such advanced coding techniques could enable transmission rates up to 200 Tb/s. However, increasing the power levels in the fiber will increase nonlinear effects, and the ultimate limit imposed by these effects is yet to be fully understood. Optical Networks From the earliest days of fiber optics, researchers envisioned optical networks that went beyond simple point-to-point systems to include multipoint switched, or at least configurable, networks. Many of the early fiber optics researchers came from the radio-frequency (RF) and microwave worlds and naturally viewed frequency-division networks, including, for example, channel-dropping filters, as obvious areas to pursue. The concept of optical switching, the routing of optical beams that could carry very high bandwidth signals, was also a natural focal point. However, technology was embryonic; primary efforts focused on optical sources and detectors, the critical enablers for point-topoint links whose technical feasibility and economic viability had to first be established. Nevertheless, a segment of early research efforts focused on the other key optical technologies and components that would one day be required to build optical networks—for example, highly functional components like tunable wavelength filters and couplers, optical switches, tunable lasers, and star couplers. Networks are fundamentally about sharing resources. Optical networks could take various shapes. The parameter around which optical networks might be based would depend upon how optical sharing or multiplexing of the transmission and distribution evolved. While many early Bell Labs researchers were predisposed to using frequency multiplexing to share the transmission resource, time division multiplexing (TDM)—driven by the digital revolution—was being implemented in backbone transmission formats. Electrical time-division multiplexing is well suited for the rates required for voice circuits as well as the much higher rates that would minimize the cost per bit for long distance backbone transmission. As discussed in the previous section, wavelength multiplexing would have to wait until TDM rates became limited by transmission impairments and the optical amplifier made WDM cost effective. By analogy with TDM systems, the evolution from simple point-to-point systems to multipoint wavelength-based networks was rather apparent16 Bell Labs Technical Journal ◆ January–March 2000 193 Wavelength multiplexer/ demultiplexer Wavelength multiplexer/ demultiplexer WDM/point-to-point transport • High-capacity transmission Fixed WDM/multipoint network • Fixed sharing between multiple nodes • Passive access of wavelength channels Photonic cross connect and WADM Reconfigured WDM/multipoint network • Automated connection provisioning • Flexible adjustment of bandwidth • Network self-healing/restoration Fiber amplifier Wavelength add/drop WADM – Wavelength add/drop multiplexer WDM – Wavelength division multiplexing Wavelength cross connect Figure 2. From photonic transport to photonic networks. (see Figure 2). While WDM point-to-point systems lier point. Once WDM transmission systems become provide very large capacity between widely spaced technically and economically feasible, by dropping (300- to 600-km) end terminals, in many networks it (and subsequently adding) only the necessary wave- is necessary to drop some traffic at intermediate points lengths, considerable cost can be saved while provid- along the route between these major nodes. One ing greater network connectivity. Wavelength could drop all that traffic (all wavelengths), but that add/drop multiplexers that can selectively drop a requires putting expensive electronics on wavelength desired wavelength while directly passing other wave- channels that could instead be expressed through tak- lengths without optoelectronic conversion are the ing advantage of the lower cost of amplifiers at an ear- required network elements. 194 Bell Labs Technical Journal ◆ January–March 2000 Network management and control Network element controller Transport interface (multiwavelength) λ1 Monitor and adjust λ1 → λi Switch fabric MUX DMUX λN → λj λN MUX DMUX Wavelength adaptation Non-compliant Compliant Client interface Client interface DMUX – Demultiplexer MUX – Multiplexer Fiber amplifier Figure 3. Configurable optical network elements. Again by analogy to TDM networks, the next logical evolutionary step would be WDM rings in which node-to-node bandwidth provisioning, as well as network protection, is based on wavelength channels (see Figure 2). To provide greater connectivity and protection from multiple failures, simple WDM rings can be interconnected to build a mesh of rings. Alternatively, a network based upon a mesh of nodes interconnected by wavelength-based paths or circuits through the net- work can be used to provide continuity and restoration in case of fiber or equipment failures. This is again the wavelength/optical analog of present electrical TDM-based networks. The optical network elements needed to build flexible wavelength-channel-based optical transport networks are wavelength add/drop multiplexers and wavelength-based optical cross connects. These network elements are shown schematically in Figure 3. Bell Labs Technical Journal ◆ January–March 2000 195 Optical components Optical systems WDM networking • Wavelength converters • Robust WDM networks • WDM cross-connect fabrics • Integrated add/drop • WDM cross connects • Dynamic gain equalizers • Ultra-wideband amplifiers • WDM rings • Wavelength monitors • Tunable lasers/couplers • WDM add/drops • WDM routers • WDM sources • Point-to-point systems • Amplifiers • Fibers WDM – Wavelength division multiplexing Figure 4. Optical components required to build robust, fully reconfigurable WDM networks. Functionally, the two elements are quite similar, differing primarily in the number of input fibers that need to be handled. Functionally, the role of each element is to provide, under network control, the ability to connect any input wavelength (optical channel) from an input fiber to any one of the output fibers or to a drop channel. In addition, the element provides power leveling, possibly wavelength monitoring and connection verification. The network also is an entry point for optical channels. Again, through network control, an added optical channel can be switched to any desired output port. To build the network elements required for multipoint optical networks, optical devices with significant optical functionality are required. Indeed, as shown in Figure 4, a host of optical components, including wavelength monitors, dynamic gain equalizers, optical switch fabrics, and wavelength converters are required to build robust, fully reconfigurable WDM networks. Fortunately, the early vision that optical networks would be dependent upon highly functional optical components and subsystems drove, in turn, the early concept and field of integrated optics. When low-loss 196 Bell Labs Technical Journal ◆ January–March 2000 fiber first suggested that fiber optic communications might be feasible, the optical functional components that existed (for example, wavelength filters) were large bulk devices. Massive mounts and stable tables were required to cascade such elements. Against this backdrop—well before it was obvious that fiber-optic communications would ever be technically or economically viable or commercially necessary—Bell Labs researchers proposed the concept of integrated optics. The idea was to build, on a single optical substrate, optical waveguide circuits based on active and passive waveguide functional components—with waveguide interconnects between the components—achieving an optical subsystem on a chip. Integrated optics was first articulated and proposed in a number of papers in the September 1969 Bell System Technical Journal.17 Several integrated optics materials systems evolved. For circuits that included active devices, optical InP (the same technology used for lasers and detectors) and titanium-diffused waveguides in the electro-optically active lithium niobate substrate have become the primary technologies.1,18 These material systems provided an early technology plat- form to build small integrated switch arrays. In fact, lithium niobate switch arrays were used to demonstrate an early multi-stage optical cross connect.19 Later, silica-on-silicon technology was developed. This has become the workhorse for passive components such as wavelength demultiplexing devices—including the waveguide grating router,20 a key element in first-generation WDM point-to-point systems and a building block for configurable wavelength add/drop multiplexers. Interestingly, even before the technical viability of the optical amplifier was demonstrated, researchers at Bell Labs in the mid 1980s were exploring the possibilities of WDM-based LANs. These included star-based networks that employed both direct and coherent detection techniques. While this work did not result in commercial products, it was important for several reasons. First, the network research provided the driver and testing ground for critical WDM optical components, such as filters, tunable sources, and WDM multiplexers. In addition, this work sparked the formation of the All-Optical Networking Consortium,21 a collaborative effort between Bell Labs (then part of AT&T), the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Lincoln Labs, and Digital Equipment Corporation (now Compaq). The consortium demonstrated the technical feasibility of local and metropolitan WDM networks based upon passive routing of optical wavelengths. The All-Optical Networking Consortium was followed by the Multi-Wavelength Optical Networking (MONET) Program. The vision of the founders of MONET was to demonstrate the feasibility of a national level end-to-end wavelength routed network based upon long-reach WDM transmission and wavelength cross connects and add/drops. The MONET consortium, funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), included AT&T, Bellcore, Bell Atlantic, BellSouth, and Southwestern Bell. 22 In its first phase, three testbeds—a local exchange WDM ring testbed, an optical cross-connect testbed, and a long distance WDM transmission testbed—were built in New Jersey. In an early demonstration, software-controlled provisioning of wavelength circuits from the local exchange ring through the cross connect and the long distance (2000 km) link and back through another node on the WDM ring showed the feasibility of wide-area optical networks.23 In the second phase of MONET, a dual-WDM ring network interconnected by a pair of optical cross connects was built in Washington, D.C. The optical add/drop and cross-connect network elements used to build this network, while prototypes, are fully operational in the field. Completed in the fall of 1999, this network is carrying live traffic between government agencies.24 Optical Access Networks A trend in the evolution of optical networks is the push of fiber from core applications out closer to the end customer. This is happening as a result of two forces: the continued drop in the cost of providing optical links, generated by improved technologies and ever-growing manufacturing volumes, and the increased bandwidth demands from users, generated by increased Internet use and applications such as video-on-demand. Large- and medium-sized business users can often be connected to core networks using low- and medium-speed synchronous-optical-network (SONET)/ synchronous-digital-hierarchy (SDH) TDM multiplexers. These can be deployed in rings to provide protection, if needed. A variety of cost-effective TDM multiplexers with tributaries having speeds as low as T1 (1.5 Mb/s) and line rates between OC-3 (155 Mb/s) and OC-48 (2.5 Gb/s) have been developed. More recently, as costs have fallen and demands have increased, some economical WDM systems have been introduced for network access. These make use of the protocol independence of WDM to transport a variety of signals, such as OC-12 (622 Mb/s) and Gigabit Ethernet (1 Gb/s), simultaneously on a single fiber. Another trend in the deployment of fiber for business use is the increasing application of fiber-based links for interconnecting enterprise data routers and switches in the LAN and campus environments. As campus backbones have moved from 10 Mb/s to 100 Mb/s or Gigabit Ethernet rates, a variety of lowcost fiber interfaces have been developed that can haul these broadband signals over distances exceeding the roughly 100-m limit of copper twisted pairs. These are Bell Labs Technical Journal ◆ January–March 2000 197 typically single-wavelength links operating bidirectionally on two separate fibers. One popular standard for fiber-based Gigabit Ethernet uses 850-nm verticalcavity surface-emitting lasers (VCSELs) and multimode fiber running distances of about 250 m. Another popular standard is based on 1310-nm edge-emitting lasers running about 5 km on SM fiber. Continuing this trend, a standard for 10-Gigabit Ethernet is expected in 2002, with initial products in 2001. At the other end of the enterprise network, copper twisted pair reigns supreme (at least today) in connecting to individual desktops. Even Gigabit Ethernet-tothe-desk appears to be attainable with twisted pair at lower cost than the most inexpensive fiber links today. It remains to be seen whether some unique advantage of fiber over copper (such as lower electromagnetic interference [EMI]) or bandwidth demands exceeding that of Gigabit Ethernet will finally drive the widespread deployment of fiber to the desk. The challenge of bringing fiber close to residential and small business customers is more difficult than for larger enterprises because of the lower willingness to pay and lower bandwidth demand. Nevertheless, this is an important challenge for several reasons. First, from the network-operator and equipment-builder perspectives, the revenues possible from widespread deployment of broadband technologies in this market are enormous. Second, there is no issue more constraining the continued growth of the Internet than the poor end-user performance seen over residential dial-up modems, which are limited to 56-kb/s capacity. Clearly, there is tremendous pent-up demand worldwide for broadband, always-on data connectivity to residences and small businesses. The challenge is to provide this in a cost-effective manner. Bringing fiber close to the customer is an essential part of the solution to this problem. Fiber is already widely deployed in residential telephony loop plant via digital loop carrier (DLC) systems. These systems use fiber to connect a central office to a remote terminal, which performs optical-toelectrical signal conversion and delivers service to several thousand living units by transferring the optical signals onto twisted pairs. Although originally engineered for voice service, DLCs can be upgraded to 198 Bell Labs Technical Journal ◆ January–March 2000 higher capacities by using one of the various forms of digital-subscriber-line (DSL) technology on the twisted pairs to the living units and by using the large bandwidth of optical fiber to connect the DLC units to the central office. In order to achieve even higher bandwidths, fiber can be economically pushed closer to the customer through the use of a passive optical network (PON).25 In a PON, a single fiber connects a central office to a passive optical splitter, which distributes the signal to about 16 optical network units (ONUs). The ONUs perform optical-to-electrical conversion and deliver service to living units. If an ONU is located at a home, this is described as a fiber-to-the-home (FTTH) system; if the ONU is shared over several (about 4 to 32) living units, this is termed a fiber-to-the-curb (FTTC) system. A PON is more cost-effective than running a fiber to every ONU because the cost of the central-office optoelectronics and the cost of the fiber between the central office and the passive splitter are shared over multiple users. A variety of PON systems have been demonstrated in the laboratory. Since many users share the fiber, an important question is how the different users should access the fiber bandwidth. The simplest approach is for all users to operate in the same wavelength band and share the bandwidth in timeslots. In the downstream (central office to ONU) direction, this is simply TDM; in the upstream direction, this is termed time division multiple access (TDMA). Unlike the LAN environment, where users are physically close to each other, collisions generated by randomly transmitting users cannot be easily detected. Thus, unlike the carrier-sense multiple-access/collision-detection (CSMA/CD) system used in Ethernet LANs, TDMA PONs typically use a protocol that grants upstream transmitters the uncontested right to transmit in a particular timeslot. Higher data throughputs can be achieved without introducing complex protocols if the PON separates user traffic on the basis of wavelength. In a WDM PON, the wavelength-independent optical splitter is replaced with a wavelength-dependent router, and each ONU communicates with the central office on its own wavelength, eliminating any bandwidth sharing. However, the cost of WDM components (particularly the unshared laser in the ONU) is still too high for this approach to be practical. A way to circumvent this problem by replacing the ONU laser with an optical modulator has been proposed.26 In this “loopback” system, a single-frequency laser in the central office illuminates the ONU modulators, allowing them to send their upstream data. A number of network operators have joined together to form the Full Service Access Network (FSAN) consortium.27,28 By specifying a common access platform that will be purchased by a large number of network operators, the FSAN hopes to drive down the cost of PON systems. The FSAN network is a coarse WDM (CWDM) PON that uses the 1.5-µm band for downstream transmissions and the 1.3-µm band for upstream transmissions. Baseband signaling at 155 Mb/s is used in each direction, with a TDMA protocol implemented for upstream transmission. Voice and data services are encapsulated into asynchronous transfer mode (ATM) cells. The FSAN work has led to a number of trials and small-scale deployments of FTTC and FTTH systems. The FSAN proposal provides a useful standard for comparing the feasibility of various higher-bandwidth PON architectures. One study compared various alternatives assuming an FSAN-like fiber network having a demand of 155 Mb/s per ONU downstream and 10 Mb/s per ONU upstream.29 WDM PONs were found incapable of providing this level of service using reasonable commercially available components. Loopback systems were unable to attain the required power budget and placed unreasonable demands on the WDM router. The most cost-effective WDM PON architecture was judged to be a composite PON (CPON), which operates as a dense-WDM (DWDM) PON with a separate wavelength for each ONU (in the 1.5-µm band) in the downstream direction and as a TDMA PON (with all ONUs sharing the entire 1.3-µm band) in the upstream direction. In addition to this work on deploying fiber closer to the customer in telephone networks, there has been a parallel deployment of fiber in the cable television (CATV) industry. Pre-fiber CATV networks typically employed very long runs of coaxial cable, with as many as 100 RF amplifiers in series to make up for the cable and tap losses. These long runs of amplifiers led to limited service bandwidths (limiting the systems to carrying only 20 to 30 television channels), poor reliability, and poor picture quality at the end of the cascade. By carrying the CATV signal optically to a fiber node that does the optical-to-electrical conversion for only 500 to 2000 living units, the amplifier cascades could be reduced to only 3 to 5 amplifiers, providing much better capacity, reliability, and picture quality.30 Since the CATV analog signal is quite fragile (unlike the baseband digital signals commonly found in telephony), special optics must be engineered for this application. Nevertheless, these hybrid fiber-coax (HFC) networks have been widely deployed for broadcast video applications. In order to become providers of data services via cable modems, CATV companies now need to reengineer their plant from being a one-way network, capable of only downstream broadcast, to a two-way network, capable of targeting data services to individual customers. One way to accomplish this while producing a plant that is more robust against noise ingress is to push the fiber closer to the customer in either an FTTC or an FTTH arrangement.31,32 These networks can provide a full set of services (analog CATV, videoon-demand, high speed Internet access via cable modem, and telephony) in a single easy-to-maintain network with good upgradability. Another approach33 for providing increased bidirectional bandwidth in CATV networks combines a broadcast analog downstream signal (amplified and split over a large number of receivers using high-power 1.5-µm EDFAs) with a set of eight DWDM channels, each carrying up to 1 Gb/s of digital data in QAM subcarrier format. At a remote node, the individual DWDM wavelengths are split apart and combined with a fraction of the analog signal. This combined signal is sent to eight separate fiber nodes. Each fiber node thus receives the broadcast analog signal along with a digital signal dedicated to its customers only. DWDM can also be used in the upstream direction, if necessary, to increase upstream capacity. This approach can be used by itself or in conjunction with a program of pushing the fiber closer to the living unit. Bell Labs Technical Journal ◆ January–March 2000 199 Some comment is appropriate on the technologies that have supported, and will continue to support, the continued push of fiber towards the customer. In access applications, cost is key. This means very lowcost optical components. In the enterprise data world, low-cost 850-nm VCSELs have been key components. For the generally longer-distance telephony networks, lower-cost lasers, particularly in the form of uncooled 1.3-µm Fabry-Perot lasers are key components. Analog-grade CATV systems have progressed from 1.3-µm DFB lasers to 1.5-µm externally modulated systems with high-power EDFAs, which have a very low cost per milliwatt. In order for DWDM systems to further penetrate access applications, the cost of DWDM components will need to fall significantly. In addition, DWDM components (sources, filters, and routers) will need to operate at stable wavelengths over the large temperature ranges required for access applications. Finally, for a DWDM PON to really make sense, a very low-cost, single-frequency laser for the ONU is required. This laser needs to be tunable over the entire wavelength range of the system so that network operators can install any ONU on any drop fiber from the router. We have seen that the last two decades have provided us with many examples of how more powerful networks can be achieved by pushing fiber closer to end users. While the ultimate goal of fiber-to-the-desk or FTTH may be sometime off, the trend toward deeper fiber penetration, driven by increased user demands and dropping costs, continues. References 1. W. F. Brinkman, T. L. Koch, D. V. Lang, and D. P. Wilt, “The Lasers Behind the Communications Revolution,” Bell Labs Tech. J., Vol. 5, No. 1, Jan.–Mar. 2000, pp. 150–167. 2. A. M. Glass, D. J. DiGiovanni, T. A. Strasser, A. Stentz, R. E. Slusher, A. E. White, and A. R. Kortan, “Advances in Fiber Optics,” Bell Labs Tech. J., Vol. 5, No. 1, Jan.–Mar. 2000, pp. 168–187. 3. R. S. Sanferrare, “Terrestrial Lightwave Systems,” AT&T Tech. J., Vol. 66, No. 1, 1987, pp. 95–107. 4. I. Jacobs, “Lightwave System Development: Looking Back and Ahead,” Optics and Photonics News, Vol. 6, No. 2, Feb. 1995, pp. 19–23. 5. A. H. Gnauck, S. K. Korotky, B. L. Kasper, 200 Bell Labs Technical Journal ◆ January–March 2000 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. J. C. Campbell, J. R. Talman, J. J. Veselka, and A. R. McCormick, “Information Bandwidth Limited Transmission at 8 Gb/s Over 68.3 km of Single-Mode Optical Fiber,” Optical Fiber Commun. Conf. (OFC’86) Tech. Digest, Postconf. Ed., Feb. 1986, Paper PD9, pp. 39–41. D. A. Fishman, J. A. Nagel, T. W. Cline, R. E. Tench, T. C. Pleiss, T. Miller, D. G. Coult, M. A. Milbrodt, P. D. Yeates, A. Chraplyvy, R. Tkach, A. B. Piccirilli, J. R. Simpson, and C. M. Miller, “A High Capacity Noncoherent FSK Lightwave Field Experiment Using Er3+-Doped Fiber Optical Amplifiers,” IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett., Vol. 2, No. 9, 1990, pp. 662–664. J. A. Nagel, S. M. Bahsoun, D. A. Fishman, D. R. Zimmerman, J. J. Thomas, and J. F. Gallagher, “Optical Amplifier System Design and Field Trial,” Optical Amplifiers and Their Applications Topical Meet. Tech. Dig., Santa Fe, N.M., Optical Soc. of America, 1992, pp. 76–82. A. R. Chraplyvy, A. H. Gnauck, R. W. Tkach, and R. M. Derosier, “8 3 10 Gb/s Transmission Through 280 km of Dispersion-Managed Fiber,” IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett., Vol. 5, No. 10, Oct. 1993, pp. 1233–1235. A. R. Chraplyvy and R. W. Tkach, “Terabit/Second Transmission Experiments,” IEEE J. of Quantum Electronics, Vol. 34, No. 11, Nov. 1998, pp. 2103–2108. T. N. Nielsen, A. J. Stentz, K. Rottwitt, D. S. Vengsarkar, Z. J. Chen, P. B. Hansen. J. H. Park, K. S. Feder, T. A. Strasser, S. Cabot, S. Stulz, D. W. Peckham, L. Hsu, C. K. Kan, A. F. Judy, J. Sulhoff, S. Y. Park, L. E. Nelson, and L. Grüner-Nielsen, “3.28-Tb/s (82 3 40 Gb/s) Transmission Over a 3 3 100 km NonzeroDispersion Fiber Using Dual C- and L-Band Hybrid Raman/Erbium-doped Inline Amplifiers,” Optical Fiber Commun. Conf. (OFC 2000) Tech. Digest, Postdeadline Papers, Mar. 2000, Paper PD23. T. Ito, K. Fukuchi, Y. Inada, T. Tsuzaki, M. Harumoto, M. Kakui, and K. Fujii, “3.2 Tb/s-1,500 km WDM Transmission Experiment Using 64 nm Hybrid Repeater Amplifiers,” Optical Fiber Commun. Conf. (OFC 2000) Tech. Digest, Postdeadline Papers, Mar. 2000, Paper PD24. H. Onaka, H. Miyata, G. Ishikawa, K. Otsuka, H. Ooi, Y. Kai, S. Kinoshita, M. Seino, H. Nishimoto, and T. Chikama, “1.1 Tb/s WDM Transmission Over a 150 km 1.3 µm ZeroDispersion Single-Mode Fiber,” Optical Fiber 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. Commun. Conf. (OFC’96) Tech. Digest, Postconf. Ed., Vol. 2, 1996, pp. 403–406. A. H. Gnauck, A. R. Chraplyvy, R. W. Tkach, J. L. Zyskind, J. W. Sulhoff, A. J. Lucero, Y. Sun, R. M. Jopson, F. Forghieri, R. M. Derosier, C. Wolf, and A. R. McCormick, “One Terabit/s Transmission Experiment,” Optical Fiber Commun. Conf. (OFC’96) Tech. Digest, Postconf. Ed., Vol. 2, 1996, pp. 407–410. T. Morioka, H. Takara, S. Kawanishi, O. Kamatani, K. Takiguchi, K. Uchiyama, M. Saruwatari, H. Takahashi, M. Yamada, T. Kanamori, and H. Ono, “100 Gbit/s 3 10 Channel OTDM/WDM Transmission Using a Single Supercontinuum WDM Source,” Optical Fiber Commun. Conf. (OFC’96) Tech. Digest, Postconf. Ed., Vol. 2, 1996, pp. 411–414. C. E. Shannon, “A Mathematical Theory of Communication,” Bell Sys. Tech. J., Vol. 27, No. 3, July 1948, pp. 379–423; Vol. 27, No. 4, Oct. 1948, pp. 623–656. R. C. Alferness, P. A. Bonenfant, C. J. Newton, K. A. Sparks, and E. L. Varma, “A Practical Vision for Optical Transport Networking,” Bell Labs Tech. J., Vol. 4, No. 1, Jan.–Mar. 1999, pp. 3–17. Bell Sys. Tech. J., Vol. 48, No. 7, Sept. 1969. R. V. Schmidt and H. Kogelnik, “Reversed DB Switch,” Appl. Phys. Lett., Vol. 26, 1978, pp. 503–505. S. S. Bergstein, A. F. Ambrose, B. H. Lee, M. T. Fatehi, E. J. Murphy, T. O. Murphy, G. W. Richards, F. Heismann, F. R. Feldman, A. Jozan, P. Peng, K. S. Liu, A. Yorinks, “A Fully Implemented Strictly Non-blocking 16 3 16 Photonic Switching System,” Optical Fiber Commun. Conf. (OFC/IOOC’93) Postdeadline Papers, Feb. 1993, Paper PD30. C. Dragone, “An N 3 N Optical Multiplexer Using a Planar Arrangement of Two Star Couplers,” IEEE Photon. Tech. Lett., Vol. 3, 1991, pp. 812–815. S. B. Alexander, R. S. Bondurant, D. Byrne, V. W. S. Chan, S. G. Finn, R. Gallager, B. S. Glance, H. A. Haus, P. Humblet, R. Jain, I. P. Kaminow, M. Karol, R. S. Kennedy, A. Kirby, H. Q. Le, A. A. M. Saleh, B. A. Schofield, J. H. Shapiro, N. K. Shankaranarayanan, R. E. Thomas, R. C. Williamson, and R. W. Wilson, “A Precompetitive Consortium on Wide-Band All-Optical Networks,” J. Lightwave Technol., Vol. 11, No. 5/6, May/June 1993, pp. 714–735. R. E. Wagner, R. C. Alferness, A. A. M. Saleh, M. S. Goodman, “MONET: Multiwavelength Optical Networking,” J. Lightwave Technol., Vol. 14, No. 6, June 1996, pp. 1349–1355. 23. R. C. Alferness, J. E. Berthold, D. Pompey, R. Tkach, “MONET: New Jersey Demonstration Network Results,” Optical Fiber Commun. Conf. (OFC’97) Tech. Digest, Vol. 6, 1997, p. 152. 24. S. R. Johnson and V. L. Nichols, “Advanced Optical Networking—Lucent’s MONET Network Elements,“ Bell Labs Tech. J., Vol. 4, No. 1, Jan.–Mar. 1999, pp. 145–162. 25. D. W. Faulkner, D. B. Payne, J. R. Stern, and J. W. Ballance, “Optical Networks for Local Loop Applications,” J. Lightwave Technol., Vol. 7, No. 11, 1989, pp. 1741–1751. 26. N. J. Frigo, P. P. Iannone, P. D. Magill, T. E. Darcie, M. M. Downs, B. N. Desai, U. Koren, T. L. Koch, C. Dragone, H. M. Presby, and G. E. Bodeep, “A Wavelength-Division Multiplexed Passive Optical Network with CostShared Components,” IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett., Vol. 6, No. 11, Nov. 1994, pp. 1365–1367. 27. Status of the Full Services Access Networks Initiative, 9th International Workshop on Optical/ Hybrid Access Networks, Access Networks MiniConference, Sessions 5 and 6 (FSAN-1 and FSAN-2), IEEE Global Telecommunications Conference (GLOBECOMM’98): Conference Record, Sydney, Australia, Nov. 10, 1998. 28. Full Service Access Network (FSAN) Initiative, <http://www.labs.bt.com/profsoc/access>. 29. R. D. Feldman, E. E. Harstead, S. Jiang, T. H. Wood, and M. Zirngibl, “An Evaluation of Architectures Incorporating Wavelength Division Multiplexing for Broadband Fiber Access,” J. Lightwave Technol., Vol. 16, No. 9, Sept. 1998, pp. 1546–1559. 30. M. R. Phillips and T. E. Darcie, “Lightwave Analog Video Transmission,” Optical Fiber Telecommunications, Vol. IIIA, edited by I. P. Kaminow and T. L. Koch, Academic Press, San Diego, Calif., 1997, pp. 523–559. 31. X. Lu, T. E. Darcie, A. H. Gnauck, and S. L. Woodward, “Low-Cost Cable Network Upgrade for Two-Way Broadband,” Proc. 1998 Conf. on Emerging Technologies, Soc. of Cable Telecomm. Engineers, Jan. 1998, pp. 83–97. 32. G. C. Wilson, T. H. Wood, J. A. Stiles, R. D. Feldman, J.-M. P. Delavaux, T. H. Daugherty, and P. D. Magill, “FiberVista: An FTTH or FTTC System Delivering Broadband Data and CATV Services,” Bell Labs Tech. J., Vol. 4, No. 1, Jan.–Mar. 1999, pp. 300–322. 33. O. J. Sniezko and T. E. Werner, “Invisible Hub or End-to-End Transparency,” Natl. Cable Television Assoc. Conf. (Cable’98) Tech. Papers, 1998, pp. 247–258. Bell Labs Technical Journal ◆ January–March 2000 201 (Manuscript approved May 2000) ROD C. ALFERNESS is Chief Technical Officer of Lucent’s Optical Networking Group in Holmdel, New Jersey. He joined Bell Labs after receiving a Ph.D. in physics from the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, where his research concerned optical propagation of volume holograms. His early research at Bell Labs centered on novel waveguide electro-optic devices and circuits— including switch/modulators, polarization controllers, and tunable filters—and their applications in highcapacity lightwave transmission and switching systems. Later, as head of the Photonic Circuits and Photonic Networks Research departments, he engaged in research in photonic integrated circuits in InP, photonic switching systems, and WDM optical networks. Dr. Alferness has authored five book chapters and over 100 papers; he also holds more than 30 patents. A fellow of both the Optical Society and the IEEE Lasers and ElectroOptics Society, he is currently editor-in-chief of the Journal of Lightwave Technology. HERWIG KOGELNIK is adjunct director of Photonics Systems Research within Bell Labs in Holmdel, New Jersey. He received both the Dipl. Ing. and doctor of technology degrees from the Technische Hochschule Wien in Vienna, Austria, and the Ph.D. degree from Oxford University in England. Dr. Kogelnik is a fellow of both the IEEE and the Optical Society of America and is an honorary fellow of St. Peter’s College in Oxford, England; he is a member of both the National Academy of Engineering and the National Academy of Sciences. His current responsibilities include research in photonic systems. THOMAS H. WOOD is a senior manager in the Advanced Technology Department of Lucent Technologies in Holmdel, New Jersey. He holds a Sc.B. degree in physics from Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, and both M.S. and Ph.D. degrees in physics from the University of Illinois in Urbana. Dr. Wood is currently responsible for optical networking technology strategy and assessment for Lucent’s Optical Networking Group. He is a fellow of the Optical Society of America. ◆ 202 Bell Labs Technical Journal ◆ January–March 2000