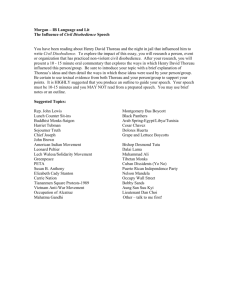

NINETEENTH-CENTURY NATURE WRITING A Thesis by Victoria Leigh Wynn

advertisement