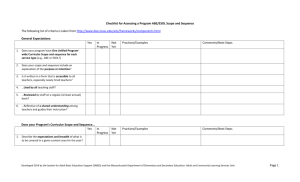

field notes

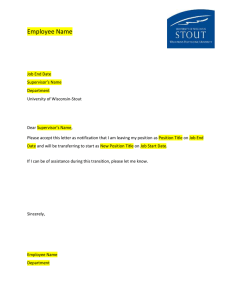

advertisement