Document 14137531

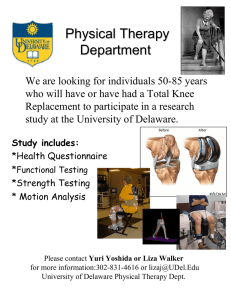

advertisement