The Federalist by Gordon Lloyd

advertisement

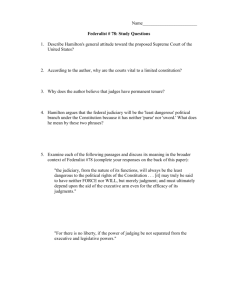

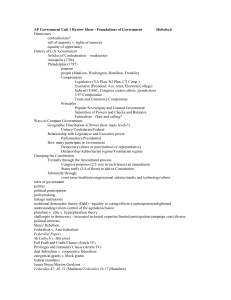

Introduction to The Federalist by Gordon Lloyd Origin of The Federalist The eighty-five essays appeared in one or more of the following four New York newspapers: 1) The New York Journal, edited by Thomas Greenleaf, 2) Independent Journal, edited by John McLean, 3) New York Advertiser, edited by Samuel and John Loudon, and 4) Daily Advertiser, edited by Francis Childs. Initially, they were intended to be a twenty essay response to the Antifederalist attacks on the Constitution that were flooding the New York newspapers right after the Constitution had been signed in Philadelphia on September 17, 1787. The Cato letters started to appear on 27 September, George Mason's objections were in circulation and the Brutus Essays were launched on 18 October. The number of essays in The Federalist was extended in response to the relentless, and effective, Antifederalist criticism of the proposed Constitution. McLean bundled the first 36 essays together—they appeared in the newspapers between 27 October 1787 and 8 January 1788—and published them as Volume 1 on March 22, 1788. Essays 37 through 77 of The Federalist appeared between 11 January and 2 April 1788. On 28 May, McLean took Federalist 37-77 as well as the yet to be published Federalist 78-85 and issued them all as Volume 2 of The Federalist. Between 14 June and 16 August, these eight remaining essays—Federalist 78-85—appeared in the Independent Journal and New York Packet. The Status of The Federalist One of the persistent questions concerning the status of The Federalist is this: is it a propaganda tract written to secure ratification of the Constitution and thus of no enduring relevance or is it the authoritative expositor of the meaning of the Constitution having a privileged position in constitutional interpretation? It is tempting to adopt the former position because 1) the essays originated in the rough and tumble of the ratification struggle. It is also tempting to 2) see The Federalist as incoherent; didn't Hamilton and Madison disagree with each other within five years of co-authoring the essays? Surely the seeds of their disagreement are sown in the very essays! 3) The essays sometimes appeared at a rate of about three per week and, according to Madison, there were occasions when the last part of an essay was being written as the first part was being typed. 1) One should not confuse self-serving propaganda with advocating a political position in a persuasive manner. After all, rhetorical skills are a vital part of the democratic electoral process and something a free people have to handle. These are op-ed pieces of the highest quality addressing the most pressing issues of the day. 2) Moreover, because Hamilton and Madison parted ways doesn't mean that they weren't in fundamental agreement in 1787-1788 about the need for a more energetic form of government. And just because they were written with a certain haste, doesn't mean that they were unreflective and not well written. Federalist 10, the most famous of all the essays, is actually the final draft of an essay that originated in Madison's Vices in 1787, matured at the Constitutional Convention in June 1787, and was refined in a letter to Jefferson in October 1787. All of Jay's essays focus on foreign policy, the heart of the Madisonian essays are Federalist 37-51 on the great difficulty of founding, and Hamilton tends to focus on the institutional features of federalism and the separation of powers. I suggest, furthermore, that the moment these essays were available in book form, they acquired a status that went beyond the more narrowly conceived objective of trying to influence the ratification of the Constitution. The Federalist now acquired a "timeless" and higher purpose, a sort of icon status equal to the very Constitution that it was defending and interpreting. And we can see this switch in tone in Federalist 37 when Madison invites his readers to contemplate the great difficulty of founding. Federalist 38, echoing Federalist 1, points to the uniqueness of the America Founding: never before had a nation been founded by the reflection and choice of multiple founders who sat down and deliberated over creating the best form of government consistent with the genius of the American people. Thomas Jefferson referred to the Constitution as the work of "demigods," and The Federalist "the best commentary on the principles of government, which ever was written." There is a coherent teaching on the constitutional aspects of a new republicanism and a new federalism in The Federalist that makes the essays attractive to readers of every generation. Authorship of The Federalist A second question about The Federalist is how many essays did each person write? James Madison—at the time a resident of New York since he was a Virginia delegate to the Confederation Congress that met in New York—John Jay, and Alexander Hamilton— both of New York—wrote these essays under the pseudonym, "Publius." So one answer to the question is that it doesn't matter since everyone signed off under the same pseudonym, "Publius." But given the icon status of The Federalist, there has been an enduring curiosity about the authorship of the essays. Although it is virtually agreed that Jay wrote only five essays, there have been several disputes over the decades concerning the distribution of the essays between Hamilton and Madison. Suffice it to note, that Madison's last contribution was Federalist 63, leaving Hamilton as the exclusive author of the nineteen Executive and Judiciary essays. Madison left New York in order to comply with the residence law in Virginia concerning eligibility for the Virginia ratifying convention. There is also widespread agreement that Madison wrote the first thirteen essays on the great difficulty of founding. There is still dispute over the authorship of Federalist 50-58, but these have persuasively been resolved in favor of Madison. Outline of The Federalist A third question concerns how to "outline" the essays into its component parts. We get some natural help from the authors themselves. Federalist 1 outlines the six topics to be discussed in the essays without providing an exact table of contents. The authors didn't know in October 1787 how many essays would be devoted to each topic. Nevertheless, if one sticks with the "formal division of the subject" outlined in the first essay, it is possible to work out the actual division of essays into the six topic areas or "points" after the fact so to speak. Martin Diamond was one of the earliest scholars to break The Federalist into its component parts. He identified Union as the subject matter of the first thirty-six Federalist essays and Republicanism as the subject matter of last forty-nine essays. There is certain neatness to this breakdown, and accuracy to the Union essays. The fist three topics outlined in Federalist 1 are 1) the utility of the union, 2) the insufficiency of the present confederation under the Articles of Confederation, and 3) the need for a government at least as energetic as the one proposed. The opening paragraph of Federalist 15 summarizes the previous fourteen essays and says: "in pursuance of the plan which I have laid down for the pursuance of the subject, the point next in order to be examined is the 'insufficiency of the present confederation.'" So we can say with confidence that Federalist 1-14 is devoted to the utility of the union. Similarly, Federalist 23 opens with the following observation: " the necessity of a Constitution, at least equally energetic as the one proposed… is the point at the examination of the examination at which we are arrived." Thus Federalist 15-22 covered the second point dealing with union or federalism. Finally, Federalist 37 makes it clear that coverage of the third point has come to an end and new beginning has arrived. And since McLean bundled the first thirty-six essays into Volume 1, we have confidence in declaring a conclusion to the coverage of the first three points all having to do with union and federalism. The difficulty with the Diamond project is that it becomes messy with respect to topics 4, 5, and 6 listed in Federalist 1: 4) the Constitution conforms to the true principles of republicanism, 5) the analogy of the Constitution to state governments, and 6) the added benefits from adopting the Constitution. Let's work our way backward. In Federalist 85, we learn that "according to the formal division of the subject of these papers announced in my first number, there would appear still to remain for discussion two points," namely, the fifth and sixth points. That leaves, "republicanism," the fourth point, as the topic for Federalist 37-84, or virtually the entire Part II of The Federalist. I propose that we substitute the word Constitutionalism for Republicanism as the subject matter for essays 37-51, reserving the appellation Republicanism for essays 52-84. This substitution is similar to the "Merits of the Constitution" designation offered by Charles Kesler in his new introduction to the Rossiter edition; the advantage of this Constitutional approach is that it helps explain why issues other than Republicanism strictly speaking are covered in Federalist 37-46. Kesler carries the Constitutional designation through to the end; I suggest we return to Republicanism with Federalist 52.