Document 14117193

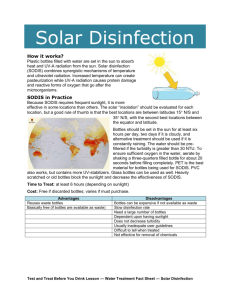

advertisement