Review of Social Economy Udaya R. Wagle

advertisement

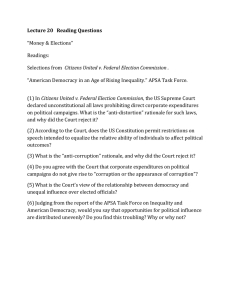

Inclusive Democracy and Economic Inequality in South Asia: Any Discernible Link? (Forthcoming in the Review of Social Economy) Udaya R. Wagle School of Public Affairs and Administration, Western Michigan University, USA Abstract Studies of the relationship between political democracy and economic inequality have produced diverse findings. This study attempts to mitigate some conceptual and methodological problems inherent in such studies by using multi-indicator concepts of inclusive democracy and economic inequality. Data from the five major historically and culturally homogeneous South Asian countries covering 1980-2003 suggest some bidirectional, positive relationship between inclusive democracy and economic inequality indicating that democracy and equality may not be fully compatible in this region. The paper offers contextual explanations and some mechanisms that may have led to these findings for the region, somewhat deviating from the conventional arguments. Keywords: Inclusive Democracy, Political and civil liberties, Democratic institutions, Economic Inequality, Panel data, South Asia I. Overview How political democracy and economic inequality interact is hardly a new issue. Much of the developed world has long embraced political democracy, where as much of the underdeveloped world has had either insularly authoritarian or other less-than democratic regimes or has switched back and forth between these. At the same time, much of the western democratic hemisphere manifests lower levels of economic inequality where as some if not most of the less-democratic countries in the South and especially in Africa and Latin America are economically more unequal. This is perhaps an overgeneralization of the breadth and depth of the interface between democracy 1 and inequality as experiences are often uniformly region, if not country, specific. No clear cleavage exists between the experiences of the democratic and authoritarian countries in their economic structures and outcomes. This paper attempts to uncover the relationship between ‘inclusive democracy’ and ‘economic inequality,’ using data covering 1980-2003 from the five major countries in South Asia— Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.1 This region includes a combination of steadily democratic polities as well as politically highly volatile countries. On the one hand is India, the largest democratic polity practicing ‘representative democracy’ the way it is popular in the western hemisphere. On the other hand is neighboring Pakistan, a notoriously autocratic regime for much of its history that is as old as India’s. Other countries are in between: Nepal is embracing constitutional monarchy where as Sri Lanka and Bangladesh have a presidential system. From the religious standpoint, Nepal is a Hindu state, Pakistan and Bangladesh are Islamic states, and India and Sri Lanka are secular states. These realities have had enormous implications for the overall political and economic landscape in each country. Since these countries are witnessing increasingly diverse economic structures, I intend to test a bidirectional relationship between inclusive democracy and economic inequality in this region. This paper is organized as follows. Next section surveys major theoretical discussions. Section three develops relevant hypothesis and describes the data with section four focusing on the trend on inclusive democracy and economic inequality in the region. Section five estimates models and presents results, which are then discussed in section six. Last section concludes with directions for future research. II. Democracy-Inequality Nexus 2 The global march for democracy in the post World War II era and a range of country performances on economic prosperity raised interest in assessing whether a part of the progress made was due to the development of democratic polities. The fact that many of the less-developed countries could not sustain democracy and turned back to authoritarianism or communism also served as an impetus to research the possible contribution of democracy to economic performance and vice versa. Some scholars, Lipset (1959), for example, saw the role of economic performance on sustaining democracy by improving the lot of those at the bottom stratum as determined by class struggle especially through universal adult suffrage. For others such as Dahl (1971), democracy provided checks and balances to undo some of the inequities produced by capitalism so that the extreme inequalities would not propagate civil unrest, threatening democracy as happened in parts of Latin America. Yet others (Lijphart 1977; Rustow 1970) observed the vision and benevolence of the elites strengthening democratic processes and institutions so that once fully operational they would not be removed by economic dynamics and misfortunes. Even the issue of how a country embraces a democratic path has drawn contentious debates with some viewing democracy to be endogenously dependent on economic development (Lipset 1959, 1994) and others finding no particular role of economic development on the evolution of democracy (Przeworski and Limongi 1997; Przeworski, Alvarez, Cheibub, and Limongi 2000). Due to the centrality of universal adult suffrage in a democratic system, inequality in economic outcomes is considered to escalate class struggles and threaten democracy (Lipset 1994; Muller 1995; Tilly 2003). While there have been increasing concerns over how worsening economic conditions of the lower classes may pose a threat to the business of democracy (Doorenspleet 2002; Lipset 1994; Muller 1988; Zafirovski 2002), democratic regimes are more likely than authoritarian regimes to introduce redistributive policies to eschew unfavorable political outcomes and survive 3 (Dahl 1971; Lipset 1959; Przeworski 2005). At the same time, many find increasing economic inequality in many western countries and particularly in the United States highly enigmatic to explain (Alderson and Nielsen 2002; Galbraith 1998). Although these countries obtain consistently high rankings on the quality of democracy, political inequalities are intense as manifested in the low levels of electoral turnout, widespread mistrust of government, and government’s unresponsiveness to minority needs (Bartels 2006; Zafirovski 2002). In case of the developing countries, on the other hand, the history of feudal or clique governments and widespread illiteracy often render regimes politically volatile. Preexisting clientelistic relationships between government officials and the public make it difficult for the latter to seek accountability from the former, resulting in massive government inefficiencies and fraud (Jeffrey 2002). As Karl (2000) contends, for example, authoritarian regimes flourish amidst high economic inequality since those in power distrust political institutions and violate human rights. Because of the affirmative role of political democracy in providing the political playing field, international development organizations vigorously promote democracy in the developing world (UNDP 2002; World Bank 2005a). Whether democracy or inequality ought to be regarded as the outcome is debatable. But it is also important to examine the effect of democracy on inequality. Because the central premise of democracy is political equality to level the playing field, it is also expected to help institute policies that redistribute resources and reduce economic inequality (Rueschemeyer 2005). Political equality, among others, guarantees political rights and civil liberties, adheres to the rule of law, and establishes processes and institutions that are accountable to the public (Beetham 2005; Dahl 1998; O’Donnell 2005). The role of the media, civil society, and competitive elections is instrumental to effect the desired policy changes (Dahl 1998; Lipset 1994). The popular median voter hypothesis, 4 for example, is one explanation of how competitive elections can help reduce economic inequality especially if the median voter’s economic position aligns with those at the lower stratum of the distribution, a very likely scenario in many countries with high inequality today. By formalizing class struggle through elections, democracy may lower economic inequality especially as median voters seek increased redistribution thus benefiting themselves and the less well off. Even in more democratic countries, however, increasing economic inequality may sometimes prove counterintuitive to the idea of political equality, class struggle, or median voter hypothesis. In the United States, for example, there are concerns that the government has been increasingly responsive to the privileged, perhaps worsening the situation of the less fortunate (APSA Task Force 2004; Jacobs and Skocpol 2006; Piven 2006; Scholzman 2006). III. Hypothesis and Data Previous studies have mostly investigated the relationship by treating either democracy or economic inequality as the outcome variable. Studies treating democracy as the outcome variable have found either significant negative effect of economic inequality (Ember, Ember, and Russett 1997; Muller 1995; Przeworski et al 2000) or no effect at all (Bollen and Grandjean 1981) suggesting that low economic inequality is at least not detrimental to democracy. Studies focusing on the effect of democracy have also found either significant negative effect (Justman and Gradstein 1999; Mahler 2004; Reuveny and Li 2003; Rodrik 1998) or no effect (Gradstein, Milanovic, and Ying 2001) suggesting that democracy does not at least inhibit the goal of reducing economic inequality. There are also suggestions that the relationship is rather curvilinear indicating that a democratic regime may fully when economic inequality is moderate (Midlarsky 1997) and/or that economic inequality may be at the pinnacle when a country is moderately democratic (Justman and Gradstein 1999; 5 Simpson 1990). While democracy and economic inequality can both be considered outcome variables and therefore estimating the bidirectional relationships may be appropriate, findings on this have also diverged. Bollen and Jackman (1995), for example, find no significant relationship where as Chong and Gradstein (2004) and Muller (1988) find significant negative relationship, further noting that democratic transformation with high inequality undermines the legitimacy of the regime, causing it to revert back to authoritarianism. Part of the reason why findings do not converge might have to do with how democracy and economic inequality are operationalized. The difference in the concept of democracy used by Bollen and Jackman (1995) and Muller (1988) is quintessential, as the former captures the substantive aspects of democracy and the latter refers to its length or stability.2 Chong and Gradstein (2004), moreover, focus on the relative strength of political institutions. Similar differences exist between using democracy as a multi-indicator construct and as a single indicator variable (Bollen 1990). On the economic inequality front, too, where as the dominant practice has been to use Gini index as its proxy measure, what basis is used to derive this measure can have profound impact on outcomes. The use of factor income, disposable income, or consumption, for example, would suggest different magnitudes of inequality, as would using the household or individual distribution and between- or within-country inequality3 (Firebaugh 2003; Milanovic 2005). Despite these differences observed mostly at the global scale, there is enough foundation to hypothesize that inclusive democracy and economic inequality have mutually reinforcing negative relationship in South Asia. An absence of this relationship would make the global project of democratization less convincing. Prior to developing other specific hypotheses dealing with how 6 inequality and democracy interact, however, it is important to provide operational definitions of the two variables. First, in line with Bollen (1990) and Bollen and Paxton (2000), I use an inclusive concept of democracy defined as ‘a set of political practices aimed at minimizing the power of the elites and maximizing that of non-elites or ordinary citizens.’ Consistent with Dahl’s (1971, 1998) nomenclature,4 this approach underscores inclusive democracy as a multi-indicator construct including development of democratic institutions and the degree of political and civil liberties.5 I use the democracy variable from the Polity IV Project (2005) dataset for the former and the aggregate of the political rights and civil liberties variables from the Freedom House (2005a) dataset for the latter. Operationalized as a composite index of ‘a mature and internally coherent democracy’ (Marshall and Jaggers 2005), the democratic institutions variable captures the development of institutions with heavy emphasis on the recruitment and functionings of the chief executive and some weight on the competitiveness of elections and political participation. As defined by the Freedom House (2005b), the political and civil liberties variable captures the political rights and freedom that people enjoy in political processes (including electoral process, political pluralism and participation) and functioning of governments and the liberties that are the cornerstones of civil life (including freedom of expression and belief, rights to join associations, rule of law and personal autonomy, and individual rights). This multi-indicator approach to measuring inclusive democracy further allows a test of more specific hypotheses involving how democratic institutions and political and civil liberties interface with economic inequality. Since the development of democratic institutions gauges the strength of the executive to pursue its own agendas with proper checks and balances, I expect to find it useful to pursue equality of opportunities and thus reduce economic inequality. Moreover, I expect the political and civil liberties variable, representing the extent of freedom people enjoy in their lives, to help level the 7 playing field, thus supporting egalitarian outcomes. Second, I broaden the concept of economic inequality to capture its different aspects involving multiple indicators. To keep the analysis theoretically consistent as well as operationally feasible, however, I use Gini index and the ratio of consumption for the top to bottom quintile as its indicators. The former indicates the deviation of the entire distribution from perfect equality, where everyone would hold exactly the same level of economic resources. Because this overall deviation fails to measure the magnitude of inequality between those on the top and bottom of the distribution, the consumption differential measuring variations at the two moderate extremes6 would complement the former. Data on these indicators are drawn from the WIDER (2005) with more recent comparable data on Nepal and Pakistan extracted from the (World Bank 2006). I expect to find both indicators of inequality to support the overall hypothesis of negative relationship with democracy. Depending on the size of the middle class, however, these two indictors may also play out differently. Finally, it is important to control for the effects of other relevant factors. The levels of economic development and globalization (per capita gross domestic product—GDP) and foreign trade are perhaps the most important of them, with their effects expected to be positive on both democracy and inequality. Other control variables include electoral participation and poverty incidence at the international threshold $1/day of income. I hypothesize that the former would negatively affect economic inequality through people’s active participation in governance and policymaking, where as the latter manifesting the economic and social vulnerability of those at the bottom of the distribution would alienate them and undermine democracy. Data on these variables are drawn from the World Bank (2005b) and IIDEA (2006). In addition, while there are a host of other potentially relevant variables including education, migration, corruption, labor market dynamics, and civic and 8 cultural activism, they are either highly correlated with the included variables or reliable data are not available on them.7 IV. A Comparative Picture Inclusive Democracy: Estimates reported in Table 1 suggest that the countries in South Asia have undergone considerable swings between democracy and authoritarianism. First, India scores consistently high on political and civil liberties and especially democratic institutions throughout the period, with all other countries experiencing major upheavals on at least one of these counts. These statistics are consistent with the movement of political processes between authoritarian and democratic regimes, with Pakistan’s movement at the former end and India’s at the latter end. (Insert Table 1 here) Statistics on political and civil liberties were comparable between the 1980s and 2000s in much of the region except in Pakistan where some progress of the 1990s significantly receded by 2000, immediately after the ascendance of the military government in power. Bangladesh and Sri Lanka made a positive move during the period, where as the situation in Nepal slightly worsened. Clearly, the democratic movement appears to have culminated in the early 1990s in Bangladesh, Nepal, and Pakistan with the formation of governments through multiparty electoral processes and the constitutional guarantee of political and civil liberties. In India and Sri Lanka, however, the 1990s registered a slight setback on the fundamental rights of citizenship as a result of escalating political violence and/or ethnic and religious tensions. In terms of the development of democratic institutions, on the other hand, surprisingly large variations existed throughout the period in Bangladesh, Nepal, and Pakistan with Sri Lanka and especially India scoring consistently high. While Nepal, Pakistan, and especially Bangladesh started out as totally autocratic regimes, 9 Bangladesh recorded a steady progress and the progress made during the 1990s in Nepal and especially Pakistan was effectively reverted back to the autocratic regime by the end of the period. Second, although the overall state of political and civil liberties remained largely unchanged during the period, the region was identifiably better positioned on the development of democratic institutions. Both country and population averages show no improvement on political and civil liberties but a remarkably high score of India with its massive population makes the state of democratic institutions considerably improve for the entire region following the population average. Overall, while average person from the region experienced well-developed democratic institutions with appropriate checks and balances, the progress of the 1990s slightly reversed by both country and population standards. Next, presented at the bottom of Table 1 are the overall inclusive democracy scores for each country and time period. These are predicted scores using a principle component factor analysis, which showed a strong commonality between political and civil liberties and democratic institutions with a large proportion of the variance being accounted for.8 These factor score estimates indicate that South Asia did not make much progress in promoting inclusive democracy from both country and population standpoints.9 The country averages show, instead, that the region on average experienced a relatively better condition of inclusive democracy in the 1990s, which receded afterwards. While Sri Lanka’s and especially India’s setback led to no net improvement in the 1990s, India is again the country that led the democratic institutionalization in the entire region. Sri Lanka’s progress was impressive during 2000-2003, where as the progress during the 1990s was impressive in Nepal, Pakistan, and especially Bangladesh. Pakistan’s progress of the 1990s, however, was dramatically undone at the turn of the century. Economic Inequality: Table 2 reports widely varying degrees of economic inequality in South 10 Asia both across countries and over time. First, Gini index based on the distribution of consumption expenditures shows that while the estimates for most of the countries and time periods were moderate, countries diverged in trend over time. Gini index was highly comparable in India, Nepal, and Pakistan in the 1980s, with Bangladesh recording the lowest estimate and Sri Lanka the highest. By 2000-2003, it slightly declined in Pakistan, moderately declined in Sri Lanka, and moderately increased in Bangladesh and India. In Nepal, by contrast, Gini index drastically soared to the levels of some highly unequal countries in the world.10 Gini index increased in South Asia between 1980s and 1990s from both country and population standpoints. (Insert Table 2 here) Second, the consumption differentials for the top and bottom quintiles slightly increased in the region between the 1980s and 1990s from the country and population standpoints with wide variations across countries. Using both country and population averages, those at the top 20 percent witnessed increased share of consumption relative to those at the bottom 20 percent by at least 33 percent. While the disparity slightly increased in India and Bangladesh during this period, it rapidly escalated in Nepal11 and yet considerably decreased in Sri Lanka and especially Pakistan. As with inclusive democracy, I used a principal component factor analysis to estimate the commonality between the two inequality indicators and predict factor scores. This process, however, was complicated due to missing values on both indicators, thus invoking some valid strategy with a delicate attention to leave the observed trend unchanged. The factor analysis conducted after imputing the relevant missing values12 indicated that the two indicators together formed economic inequality with a large commonality.13 Results summarized in Table 2 indicate a relatively wide variation in economic inequality in the region.14 The values for Nepal characterizing the highest degree of inequality in South Asia are starkly different from those in Sri Lanka during 11 2000-2003. These estimates capture the commendable stride that Pakistan and especially Sri Lanka made in reducing inequality during the period. Where as Sri Lanka and especially Pakistan started with moderate degrees of inequality in the 1980s, they both progressively reduced inequality by the end of the period. Bangladesh with a very low level of inequality to begin with managed to maintain it throughout the period even though at a slightly higher level. India and especially Nepal manifest a rampant increase in inequality. V. Models and Results Since disentangling the interrelationships between democracy and economic inequality is complex, I use various techniques to efficiently handle this complexity. The use of fixed effects regressions is justified given the balanced panel data in which it is important to control for the country specific effects. The use of the three-stage least squares (3SLS) regression is also relevant given its ability to account for any endogeneity and simultaneous causality bias. Because regression models sometimes produce estimates due to random chance, I conduct sensitivity analysis by estimating alternative specifications of the models with the aggregate scores on democracy and inequality as well as with their indicators as the dependent variables.15 Panel Data Models: I estimate fixed effects regressions with the following specification: y it = α + β x it + γwit + u i + ε it Where, y is the dependent variable democracy or economic inequality; x is the independent variable economic inequality or democracy; w is the vector of control variables; and u is the country specific error. I estimate four alternative specifications of this model with the first two including democracy scores as the dependent variable and other two including the indicators of democracy as the dependent variables. I also estimate two sets of alternative specifications of the model, of which the first includes inequality scores as the dependent variable and the next includes the indicators of 12 inequality as the dependent variables. First, estimates from the fixed effects regressions of democracy included in Table 316 indicate that the models with the aggregate economic inequality scores as the independent variable demonstrate relatively small explanatory power compared with those with their indicators.17 Results from the Democracy I model suggest that the effect of inequality is positive on inclusive democracy. While this effect is not statistically highly significant due perhaps to the composite nature of the independent variable, the more unequal countries in South Asia tend to develop more inclusive democracy. Providing highly consistent sets of estimates, results from the Democracy II, Liberties, and Institutions models with the indicators of inequality as the independent variables suggest that the role of inequality in determining inclusive democracy bifurcates into the positive effect of Gini index and the negative effect of the 80/20 consumption differential. The effects of Gini index on inclusive democracy as well as political and civil liberties and democratic institutions are all positive suggesting that more unequal countries tend to institute more inclusive democracy. The negative association of the consumption ratio, however, suggests that larger consumption differentials would be detrimental to inclusive democracy in aggregate as well as to the specific indicators. (Insert Table 3 here) The coefficients on the control variables are partly consistent with my expectations. The GDP per capita, for example, has a consistently positive relationship with democracy indicating that South Asian countries with higher levels of economic development tend to be more democratic (Lipset 1959; Przeworski and Limongi 1997). Contrary to my expectation, the effect of poverty incidence is also consistently positive. Although the moderate correlation of poverty incidence with GDP (– 0.70) rules out a severe multicollinearity problem, these coefficients indicate something related but 13 beyond the effect of GDP. Since GDP positively affects democracy, some of this effect tends to be negated especially when a country has a high poverty incidence. The curvilinear nature of the relationship that studies have shown elsewhere (e.g., Bollen and Jackman 1995; Muller 1995) also appears to be operational in this region once the positive effect of poverty incidence is incorporated. While the finding that democracy flourishes amidst high degrees of absolute poverty is hard to accept, this does not support the argument that a high degree of absolute poverty induces people to get organized and pressure for more political equality. Because poverty concentration correlates (0.82) highly with illiteracy, the argument for articulating organized voices for more freedom as well as for further development of democratic institutions is also not supported. Second, estimates from the fixed effects regressions presented in Table 4 suggest that the effects on the aggregate measure of inequality are not significant in case of both the aggregate measure of democracy (Inequality I) and individual indicators (Inequality II). Results from the 80/20 and Gini models, however, demonstrate that the indicators of democracy systematically affect the two aspects of economic inequality captured by the respective indictors. Interestingly, findings are quite different between using the aggregate measures of inequality and democracy and using their indicators. But, consistent with the effects of inequality on democracy, the effect of democracy on inequality also bifurcates, suggesting that while political and civil liberties are negatively related with the inequality indicators, democratic institutions are positively related with them. There is an indication that countries with more freedom have maintained lower levels of inequality, where as those with more established democratic institutions tolerate more inequality. What may be different, however, is the interaction of the democracy indicators in affecting the aggregate measure of inequality resulting in an insignificant coefficient. (Insert Table 4 here) 14 The effects of control variables on inequality partly support the hypotheses posed earlier. The models indicate that electoral participation does not directly affect inequality in South Asia, where as a higher GDP significantly reduces it. Electoral participation typically entails that people are knowledgeable of, as well as interested in, their own governance or influencing policy outcomes, an assumption that may not hold in this region with mass illiteracy. In the same vein, while the negative coefficient on GDP partly contradicts the popular findings (Barro 2000; Reuveny and Li 2003), a little over two decades may not be adequate to realistically capture the time series relationships. Also, South Asian countries with larger GDP estimates have been able to curb economic inequality perhaps suggesting that it is not necessarily the economic growth that increases inequality. What matters more, for example, may be the policy prescriptions on labor market and income redistribution, which have not been fully captured in the analysis. This is further supported by the positive coefficient on international trade, which is consistent with the hypothesis posed earlier. It may be natural to expect that more open or liberalized economies tend to be more unequal. This result, just like those from other more systematic investigations in South Asia (Wagle 2007a), does not support the oft-cited Stolper-Samuelson (1941) hypothesis that countries with increasing foreign trade would witness declining economic inequality through migration of the abundant unskilled and skilled workers. As expected, economic expansion triggered by the liberalization policies of the 1980s and especially 1990s may have increased the demand for the unskilled labor. But their real compensation may not have increased in South Asia, where the unskilled labor is abundant, relative to the skilled labor that is in short supply. Yet, the fact that GDP linearly decreases inequality where as foreign trade increases it may indicate that the effects of economic development and openness greatly interact each other, making inequality a nonlinear outcome. 15 3SLS Models: To correct for any endogeneity and simultaneity bias, I estimate the following simultaneous system of equations:18 yit = β 0 + β 1 xit + β 2 wit + u it xit = γ 0 + γ 1 y it + γ 2 wit + vit Where, y is the inclusive democracy, x is the economic inequality, and w is the vector of control variables. Note that just like in fixed effects regressions, there will be two separate specifications with the first including the composite measures of inclusive democracy and economic inequality and the second replacing them with the respective indicators. Unlike with panel data techniques, however, I estimate models with the composite scores of democracy and inequality as the dependent variables. Also, I estimate both unweighted and weighted versions of the model given the potential effects of the population size. (Insert Table 5 here) Results reported in Table 5 suggest two noteworthy points. First, where as the Unweighted I model provides significant coefficients on the composite scores as the independent variables, the estimates from the Weighted I model are less significant. The country level analysis, therefore, shows largely positive relationships between the two sets of composite scores signifying bidirectional relationships. Different from the panel data technique, however, the nonlinear effect of democracy is significant suggesting that its positive effect on inequality sustains in a bidirectional environment, which tends to attenuate after a country attains certain level of democracy. The relationships between the composite scores of democracy and inequality and relevant indicators are partly consistent between both the 3SLS models and the panel data models. In case of the weighted models, however, the coefficients on the aggregate measure of democracy and its indicators are not significant. Partly, this predicates the relevance of the unweighted models in the 3SLS environment together with the fixed effects regressions of inequality. 16 Second, the roles of control variables in determining democracy and inequality are mostly consistent with those suggested earlier. Unlike in the panel data regressions, the coefficient on electoral participation is significant only in the Unweighted I model. This mostly significant and positive effect of electoral participation contradicts the median voter hypothesis suggesting that wider participation does not always result in more redistributive policies. Given that elections are not always held within a multiparty, competitive framework in South Asia, however, their meaning as well as the meaning of participation are not consistent. The role of GDP too appears to be insignificant in the Weighted I model. The massive population in India with low GDP, stable electoral participation, high democracy scores, and yet already high and rising inequality may have caused some vulnerability of the weighted models. The coefficients on country specific dummies are also interesting and yet mostly unsurprising. VI. Discussions This analysis supports that inclusive democracy and economic inequality may have mutually reinforcing relationships with each affecting the other in South Asia. It instructs to reject the hypothesis that the aggregate relationship is negative and indicates that while it may be nonlinear and perhaps marginal especially in terms of the effect of democracy on inequality, it is positive both ways. These relationships are not fully consistent with the effects of their underlying indicators that have opposite signs. But the aggregate net relationship appears to be positive, after accounting for any relevant dynamics involved in collectively determining them. Here, the story that the models with individual indicators help craft will be useful to understand the mechanisms specific to this region. First, while the net effect of economic inequality on inclusive democracy is positive, one can see interesting dynamics with regard to the effects of the 17 individual inequality indicators. The model estimates consistently show that a large Gini index characterizing a relatively high degree of economic inequality increases the chance of having inclusive democracy. At the same time, however, having large resource differences for those at the top and bottom quintile can be detrimental to democratization. While there are disagreements over the central role of different classes in democratization with some focusing on the bourgeoisie, others on the middle class, and yet others on the working class, all arguments point that democratization transforms the social stratification system (Bollen and Jackman 1995). Research largely supports, however, that a powerful middle class is needed to effect and sustain democracy, as it can effectively pressure for democratic outcomes affecting the masses (Dahl 1971; Easterly 2005; Lipset 1959). In South Asia, too, the middle class with a large student and working population has provided a strong impetus to bring about democratic changes. As many countries have switched between democratic and authoritarian governments in this region, the main sticking point has been a constant struggle between the land-owning, bureaucratic elites and the working, middle class. The findings with the negative role of 80/20 consumption differential and positive role of Gini index subtly substantiate this tension. The negative role of the consumption differential, for example, captures the power of the elites to maneuver the rulers so that the demand for the political rights and civil liberties can be suppressed and their influence in policy decisions can be sustained (Benhabib and Przeworski 2006; Easterly 2005). The rulers also find collusion with the elites rewarding as it avoids institutional constraints to their recruitment and functioning (Przeworski 2004). The mostly agrarian and illiterate setting especially in rural villages in many countries with clientelistic relationships between government and the public makes it highly likely that the real separation of economic and political powers is only a myth. 18 No doubt, more democratic countries like India have been able to strengthen individual rights and liberties and electoral participation as a result of more inclusionary policies. Despite this, however, the underrepresentation of the lower classes in important political, policy, and bureaucratic processes continues to persist in South Asia. Jeffrey (2000, 2002) shows, for example, that the elites dominate the political and bureaucratic machinery in north India, systematically excluding and marginalizing the lower classes. India as a whole also continues to witness a disproportionately lower representation of the different minorities including the Christians, Muslims, and Dalits in political leaderships and administrative services (Manchanda 2006). More important than the quantity of representation is its quality, however, with any increase in representation of these groups in less crucial places not having significant influence in the actual policy decisions. In Nepal, in particular, the upper caste Hindus comprising slightly greater than 30 percent of the total population occupy almost two thirds of the major public sector positions with indigenous groups, Muslims, and Dalits disproportionately far behind (Lawoti 2005; Manchanda 2006). Similar observations hold for the Tamils and Christians in Sri Lanka and, perhaps at a smaller scale, the Hindus and Christians in Bangladesh and Pakistan not only in political and bureaucratic representation but, more importantly, in maintaining various aspects of individual liberty. The positive role of Gini index, on the other hand, manifests the power of the middle class to organize and pressure for democratic outcomes. While Gini index does not readily measure the power or the size of the middle class, it does so after accounting for the extreme degrees of inequality manifested by the consumption differential.19 And when the middle class is large, especially experiencing more intense inequality, it looks for ways to establish democracy thus protecting political and civil liberties and institutionalizing governments. The middle class may be economically disadvantaged thus contributing to larger Gini indexes but its use of pluralistic 19 mechanisms such as labor unions, farmers’ cooperatives, and women’s associations that are operational in both democratic and authoritarian countries to various degrees increases the chance of democratic outcomes (Dahl 1971, 1998; Lipset 1959, 1994). Second, results consistently support that higher levels of individual freedom help make governments accountable to the public, thus favoring equality in opportunity and outcomes. This offers a rich understanding of the mechanism through which democracy affects inequality. The findings suggest a constant juxtaposition of the positive effect of democratic institutions with the negative effect of freedom, yielding a positive but sometimes insignificant net effect. Political and civil liberties enable one to use not just the means such as elections or other political activities including protests, rallies, and demonstrations to effect desired policy changes. They also provide other means especially through the rule of law, freedom of expression, and freedom to practice civic and cultural life that can help shape the public opinion and pressure the government for appropriate policy measures. While the performance of South Asian countries on securing political and civil liberties has not been highly variable—all ranging from two to 5.5 out of the highest possible score of seven—its negative effect on inequality captures the strength of freedom that people are able to enjoy. This supports the thesis that political equality tends to level the playing field and promote equality in economic outcomes (Justman and Gradstein 1999; Rueschemeyer 2005). At the same time, the negative effect of political and civil liberties on both measures of inequality is interesting. The effect on Gini coefficient may predicate the role of redistribution benefiting the middle class, the lower class, or both. While similar dynamics may hold, the effect on the 80/20 consumption differential may also imply that the lower class has become worse off, a possibility with redistribution from the upper class to the middle class. The positive role of political institutions is also quite interesting because of its power to drive the 20 net effect of democracy on inequality. The democratic institutions variable captures the institutional aspect of democracy including development of proper checks and balances, competitive recruitment of the chief executive, and public support needed to lead the institutions. In South Asia where economic growth is always a top priority, however, this notion of democratic institutionalization may provide a license to pursue one’s growth agendas without much operational constraint. The notion of social hierarchy and clientelism is embedded in the culture with caste, ethnicity, and other hierarchies determining the social order and outcomes (Bista 1991; Jeffrey 2002; Przeworski 2004; Przeworski et al 2000). In countries with no formal checks and balances, on the other hand, the chief executive constantly feels a need to legitimize authority and actions from citizens and international actors. While the ruler ascends to power using some political justifications, the possibility of mass uprising and the legitimization problem may force the autocratic ruler to introduce populist programs (Benhabib and Przeworski 2006; Gandhi and Przeworski 2006). It may not veritably redistribute resources but it does help boost consumption among the poor thus reducing inequality. Unlike with political and civil liberties, however, the consistently positive effect of democratic institutions suggests that the upper class tends to benefit as a result of greater democracy, a finding consistent with the ability of the upper class to influence the making and implementation of policies. VII. Conclusion If empirical data are any guide, democracy in this region appears to fuel economic inequality, which in turn may promote democracy. While the relationship may not be perfectly linear especially in case of the effect of democracy on inequality and while it is not highly consistent across different modeling environments, there is evidence for a bidirectional positive relationship. There are 21 interesting observations on how these relationships come about. The positive effect of Gini index and the negative effect of the 80/20 consumption differential on democracy, for example, contradict each other, as do the positive effect of democratic institutions and negative effect of political and civil liberties. After controlling for the negative effect of the consumption differential suggesting that the existence of super elites (together with ultra poor) drags the efforts to democratize, the positive effect of Gini index indicates that the large, economically less-advantaged middle class pressures for democratic institutions and political equality. Moreover, political institutions embracing clientelistic culture and pursuing the overall economic growth policies undermine their economic redistribution agenda, where as the political and civil liberties adhere to the rule of law, free media, and vibrant civil society which can effectively pressure the state to equalize opportunities and reduce extreme inequalities. There may be several reasons for the seemingly unusual findings, which this study has uncovered for South Asia, with two most important being contextual and methodological. Using extensive comparative data, Gradstein et al (2001) found a strong intervening role of religion or culture when it comes to determining the effect of democracy on inequality. For Muslim and Buddhist/Hindu dominant societies, they note, “democracy has either hardly discernible, or even a positive, effect on inequality” (Gradstein et al 2001). While the attempt to control for these religious differences was not fruitful perhaps because of the small sample size, what is at play is clearly the culture that values economic inequality perhaps even more than it values democracy. There may be social processes and institutions in this region that constantly look after the disadvantaged or hold the rich morally obligated to support the poor in ways without extensive state involvement. It is not the policy context or democratic governance per se that produces the economic outcomes affecting the fate of the masses in these countries. Where as the policy priorities and operational 22 modalities change in western democracies following changes in the government, this may tend to be highly invariant in South Asia regardless of whether the ‘democratic framework’ is operational. Bureaucracies in these countries tend to be relatively strong and resistant to political influence and therefore political parties in power might not have as much a sway over the redistributive nature of policies. Party politics, from this standpoint, may only obstruct the process by which governments are expected to favor certain constituencies. Authoritarian governments may even get increasing pressure to legitimize their regimes, thus giving continuity to their populist, redistributive policies benefiting the lower classes. From the methodological standpoint, comparative analyses like this invoke enormous data issues especially on inequality measures. In this analysis, I use consumption rather than income or expenditure data to maintain consistency across countries and over time. While the WIDER (2005) does an excellent job at adding consistency and reliability to the data, inequality estimates were unavailable for many years. Because these inequality estimates have to come from nationally representative surveys, they are simply hard to come by. Despite a meticulous handling of the missing values, the outcomes may not have reflected the actual country experiences. Also, the degrees of inequality examined here using consumption estimates may have been smaller than what they actually are as inequality in market incomes tends to run much higher. More comprehensive and consistent data are needed to derive more conclusive findings. The dynamic nature of the concepts of democracy and inequality in this region may necessitate incorporation of the time as well as country specific effects in the analysis. Researchers need to pay appropriate attention to the effects of globalization and other international political economy factors as well as to the horizontal and spatial forms of inequality that have enormous implications for the participation of different groups in the political processes and for the quality of democracy. 23 Endnotes 1 While the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) includes seven official member-countries, Bhutan and Maldives are not included in this analysis for lack data. 2 This also applies to others examining various dimensions of democracy (Benhabib and Przeworski 2006; Przeworski et al 2000; Przeworski and Limongi 1997). 3 It is important to distinguish between vertical and horizontal inequality within a country. The horizontal or between- group inequality is important for a discussion of democracy as it partly shapes various political processes, institutions, and outcomes. The various forms of ethno-political conflicts and instability facing many countries in South Asia, for example, may have to do with growing inter-group economic disparities along caste, ethnic, religious, and spatial lines (Deshpande 2000; Manchanda 2006; Wagle 2007b). Despite this, however, this paper exclusively focuses on the vertical or inter-individual inequality for consistent data on horizontal inequality are not available. 4 In his most recent treatise, for example, Dahl (1998) outlines basic ingredients of political democracy as effective participation, voting equality, enlightened understanding, control of the agenda, and inclusion of adults in democratic processes. 5 Included here are the institutional factors mainly used by political scientists. Alternative approaches increasingly used by political economists underscore individual factors such as human development and other positive freedoms (O’Donnell 2004; Sen 1999). 6 The 90/10 ratio is another variation of the percentile distribution with a more radical tone as one is likely to find larger differences from this approach than from the 80/20 approach (Sutcliffe 2004). 7 See Appendix for a description of the variables used. 8 Factor analysis finds commonality among the variables supplied and empirically determines the weights useful in predicting factor scores. Although this approach provides equivalent loading weights when two variables are used, results indicated that the first common factor with an Eigenvalue of 1.6505 accounted for over 82 percent of the total variation thus rendering the predicted scores highly accurate. 24 9 There is a caveat in terms of making absolute comparisons with these estimates, however. Because these factor scores have a range of 0-1, the variations between countries and over years may have been slightly magnified. As a result, the values are only relative to the estimates in this distribution and cannot be compared with any other estimates. The value of one, for example, indicates its highest ranking in the distribution, not a perfect case for inclusive democracy, where as the value of zero indicates the lowest in the distribution, not a case with absolutely no democracy. 10 Its Gini index of 0.47 compares well to those of the most unequal countries including Argentina (0.528), Mexico (0.495), the Philippines (0.46), and South Africa (0.578) (World Bank 2006). 11 Looking at the distribution of income, Guha-Khasnobis and Bari (2003) found similar patterns in South Asia with Nepal manifesting the highest ratio of income for the top to bottom deciles followed by Pakistan. 12 Because these inequality data come from nationally representative surveys, estimates are available only for some years. To derive reliable estimates for the years in a given country, I linearly interpolated the data thus leaving the overall trend intact. In many cases, however, estimates were not available for a few years in or after 1980 and /or in or prior to 2003. Specifically, Bangladesh lacked estimates prior to 1983 and after 2000, India after 2000, Nepal prior to 1984, Pakistan prior to 1984 and after 2002, and Sri Lanka prior to 1986 and after 2000. In these cases, I extrapolated the data by extending the actual value of the closest estimate to the beginning or to the end. While this does not capture the true state of inequality for the given year, it systematically inputs values that are highly probable. Because values in the time series data can change from one year to next only by marginal percentage points, this process still leads to outcomes that are justifiably realistic. 13 The process was akin to the case of inclusive democracy discussed earlier. In this case, however, the proportion of the commonality accounted for was 96 percent with an eigenvalue of 1.918 indicating even greater confidence on the accuracy of the predicted scores. 14 Such variations, however, may have been greatly magnified precisely because of the relative comparison among the cases involved. See footnote 9 for details. 15 This is to examine the potential multicollinearity problems likely in these types of aggregate data. The use of multiple, correlated democracy or inequality indicators in the same model, for example, increases the chance of multicollinearity, which can be corrected, among other things, by using their aggregate estimates. 25 16 I estimated random effects counterparts of the models presented in Tables 3 and 4 to see whether they produce equally consistent estimates. Coefficient estimates were mostly similar and the associated Hausman test results indicated that in most cases the differences in coefficients were systematic between the fixed and random effects regressions (results available from the author). 17 The use of specific indicators increases the explanatory power of the model, because of the aggregate nature of democracy as well as the inclusion of more independent variables. 18 Although the equations include panel data notations, the model itself does not represent a panel data technique. But the inclusion of country specific dummy variables makes the model equivalent to a fixed effects regression. 19 Consumption differential, which captures the disparities between the rich and the poor, is an integral part of Gini index. Once the model controls for the effect of consumption differential, the value added of using Gini index becomes the degree of inequality experienced by the middle class. Here, middle class is defined as the group whose consumption is close to the mean. Since the typical distribution of income or consumption has positive skewness with long upper tail, a higher degree of consumption differential would render a smaller middle class, as the mean would center somewhere in the upper half of the distribution, away from the median. Since those on the top manifest high consumption, this would also be consistent with the more intense inequality experienced by the middle class. References Alderson, A.S. and Nielsen, F. (2002). Globalization and the Great U-Turn: Income Inequality Trends in 16 OECD Countries. American Journal of Sociology, 107(5), 1244-99. APSA Task Force on Inequality and American Democracy. (2004). American Democracy in an Age of Rising Inequality. Perspectives on Politics, 2(4), 651-66. Barro, R.J. (2000). Inequality and Growth in a Panel of Countries. Journal of Economic Growth, 5, 5-32. Bartels, L.M. (2006). Is the Water Rising? Reflections on Inequality and American Democracy. PS, Political Science & Politics, 39(1), 39-42. Beetham, D. (2005). Freedom and the Foundation. In L. Diamond and L. Morlino (Eds.), Assessing the Quality of Democracy, pp. 32-46. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. 26 Benhabib, J. and Przeworski, A. (2006). The Political Economy of Redistribution Under Democracy. Economic Theory, 29, 271-90. Bista, D.B. (1991). Fatalism and Development: Nepal’s Struggle for Modernization. Calcutta, India: Orient Longman. Bollen, K.A. (1990). Political Democracy: Conceptual and Measurement Traps. Studies in Comparative International Development, 25(1), 7-24. Bollen, K.A. and Grandjean, B. (1981). Dimension(s) of Democracy: Further Issues in the Measurement and effects of Political Democracy. American Sociological Review, 46, 651-59. Bollen, K.A. and Jackman, R.W. (1995). Income Inequality and Democratization Revisited: Comment on Muller. American Sociological Review, 60, 983-89. Bollen, K.A. and Paxton, P.M. (2000). Subjective Measures of Liberal Democracy. Comparative Political Studies, 33(1), 58-86. Chong, A. and Gradstein, M. (2004). Inequality and Institutions. CEPR Discussion Paper No. 4739. Dahl, R.A. (1998). On Democracy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Dahl. R.A. (1971). Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Deshpande, A. (2000). Recasting Economic Inequality. Review of Social Economy, LVIII(3), 38199. Doorenspleet, R. (2002). Development, Class, and Democracy: Is there a Relationship? In O. Elgstrom and G. Hayden (Eds.), Development and Democracy: What Have We Learned and How?, pp. 48-64. New York, NY: Routledge. Easterly, W. (2005). Inequality Does Cause Underdevelopment. New York University, New York (Mimeo). Ember, M., Ember, C.R., and Russett, B. (1997). Inequality and Democracy in the Anthropological Record. In M.I. Midlarsky (Ed.), Inequality, Democracy, and Economic Development, pp. 110-30. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. Firebaugh, G. (2003). The New Geography of Global Income Inequality. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Freedom House. (2005a). Freedom in the World Country Rankings: 1972-2004. Washington, DC: Freedom House. Freedom House. (2005b). Freedom in the World: Methodology. Washington, DC: Freedom House. 27 Galbraith, J.K. (1998). Created Unequal: The Crisis in American Pay. New York, NY: Free Press. Gandhi, J. and Przeworski, A. (2006). Cooperation, Cooptation, and Rebellion Under Dictatorships. Economics and Politics, 18(1), 1-26. Gradstein, M., Milanovic, B., and Ying, Y. (2001). Democracy and Income Inequality: An Empirical Analysis. World Bank DRG Policy Research Working Paper 2561. Guha-Khasnobis, B. and Bari, F. (2003). Sources of Growth in South Asian Countries. In I. Ahluwalia and J. Williamson (Eds.), The South Asian Experience with Growth, pp. 13-79. New York: Oxford University Press. IIDEA. (2006). Online Voter Turnout Database. International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, Stockholm, Sweden. Jacobs, L.R. and Skocpol, T. (2006). Restoring the Tradition of Rigor and Relevance to Political Science. PS, Political Science & Politics, 39(1), 27-31. Jeffrey, C. (2000). Democratization without Representation? The Power and Political Strategies of a Rural Elite in North India. Political Geography, 19, 1013-36. Jeffrey, C. (2002). Caste, class, and Clientelism: A Political Economy of Everyday Corruption in Rural North India. Economic Geography, 78(1), 21-41. Justman, M. and Gradstein, M. (1999). The Industrial Revolution, Political Transition, and the Subsequent Decline in Inequality in 19th–Century Britain. Explorations in Economic History, 36, 109-27. Karl, T.L. (2000). Economic Inequality and Democratic Instability. Journal of Democracy, 11(1), 149-156. Lawoti, M. (2005). Towards A Democratic Nepal: Inclusive Political Institutions for a Multicultural Society. New Delhi: Sage. Lijphart, A. (1977). Democracy in Plural Societies. A Comparative Exploration. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Lipset, S.M. (1959). Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Development. American Political Science Review, 53, 69-105. Lipset, S.M. (1994). The Social Requisites of Democracy Revisited. American Sociological Review, 59, 1-22. Mahler, V.A. (2004). Economic Globalization, Domestic Politics, and Income Inequality in the Developed Countries: A Cross-National Study. Comparative Political Studies, 37(9), 1025-53. 28 Manchanda, R. (Ed.). (2006). The No-Nonsense Guide to Minority Rights in South Asia. Kathmandu, Nepal: South Asian Forum for Human Rights. Marshall, M.G. and Jaggers, K. (2005). Polity IV Project: Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions: 1800-2002. Polity IV Project (INCSR). Midlarsky, M.I. (1997). Conclusion: Paradoxes of Democracy. In M.I. Midlarsky (Ed.), Inequality, Democracy, and Economic Development, pp. 319-26. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. Milanovic, B. (2005). Worlds Apart: Measuring International and Global Inequality. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Muller, E.N. (1988). Democracy, Economic Development, and Income Inequality. American Sociological Review, 53, 50-68. Muller, E.N. (1995). Economic Determinants of Democracy. American Sociological Review, 60, 966-82. O’Donnell, G. (2004). Human Development, Human Rights, and Democracy. In G. O’Donnell, J.V. Cullell, and O.M Iazzetta (Eds.), The Quality of Democracy: Theory and Applications, pp. 9-92. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press. O’Donnell, G. (2005). Why the Rule of Law Matters. In L. Diamond and L. Morlino (Eds.), Assessing the Quality of Democracy, pp. 3-17. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. Piven, F.F. (2006). Response to “American Democracy in an Age of Inequality.” PS, Political Science & Politics, 39(1), 43-46. Polity IV Project. (2005). Polity IV Annual Time Series Dataset. INCSR, University of Maryland, College Park, MD. Przeworski, A. (2004). Institutions Matter? Government and Opposition, 39(4), 527-40. Przeworski, A. (2005). Democracy as an Equilibrium. Public Choice, 123, 253-73. Przeworski, A. and Limongi, F. (1997). Modernization: Theories and Facts. World Politics, 49(2), 155-83. Przeworski, A., Alvarez, M.E., Cheibub, J.A., and Limongi, F. (2000). Democracy and Development. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. Reuveny, R. and Li, Q. (2003). Economic Openness, Democracy, and Income Inequality: An Empirical Analysis. Comparative Political Studies, 36(5), 575-601. Rodrik, D. (1998). Symposium on Globalization in Perspective: And Introduction. Journal of 29 Economic Perspectives, 12(4), 3-8. Rueschemeyer, D. (2005). Addressing Inequality. In L. Diamond and L. Morlino (Eds.), Assessing the Quality of Democracy, pp. 47-61. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. Rustow, D.A. (1970). Transitions to Democracy: Toward a Dynamic Model. Comparative Politics, 2, 337-63. Scholzman, K.L. (2006). On Inequality and Political Voice: Response to Stephen Earl Bennett’s Critique. PS, Political Science & Politics, 39(1), 55-57. Sen, A.K. (1999). Development as Freedom. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knoff. Simpson, M. (1990). Political Rights and Income Inequality: A Cross-National Test. American Sociological Review, 55, 682-693. Stolper, W.F. and Samuelson, P.A. (1941). Protection and Real Wages. Review of Economic Studies, 9, 5873. Sutcliffe, B. (2004). World Inequality and Globalization. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 20(1), 15-37. Tilly, C. (2003). Inequality, Democratization, and De-Democratization. Sociological Theory, 21(1), 37-43. UNDP. (2002). Human Development Report 2002. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Wagle, U. (2007a). Are Economic Liberalization and Equality Compatible? Evidence from South Asia. World Development, 35(11), 1836-57. Wagle, U. (2007b). Economic Inequality in the ‘Democratic’ Nepal: Scale, Sources, and Implications. Himalayan Policy Research Conference, October, Madison, WI. WIDER. (2005). World Income Inequality Database (V 2.0a). World Institute for Development Economics Research (United Nations University). World Bank. (2005a). World Development Report 2005. Washington, DC: The World Bank. World Bank. (2005b). World Development Indicators 1960-2005 (CD-ROM). Washington, DC: The World Bank. World Bank. (2006). World Development Report 2006. Washington, DC: The World Bank. Zafirovski, M. (2002). Income Inequality and Social Institutions: Beyond the Kuznets Curve and Economic Determinism. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 22(11/12), 89-131. 30 Appendix. Description of Variables Variables Economic Inequality Gini Index Definition Composite scores predicted from Gini Index and 80/20 Consumption, using weights empirically determined by factor analysis. ab Gini coefficient of the distribution of per capita consumpotion expenditures. Possible values are between 0.25 zerotoand 0.47one with, zero indicating perfect equality an ab 80/20 Consumption Inclusive Democracy c Political and Civil Liberties d Democratic Institutions Ratio of the share of consumption expenditures of the top to bottom quintile. Composite scores predicted from Political and Civil Liberties and Democratic Institutions, using the weights empirically determined by factor analysis. Simple average of the scores of political rights and civil liberites, each ranging from one to zeven. While the original data were in descending order, the reconstructed scales have positive order with one signifying the lowest score and seven signifying the highest or ideal score. Scores on democratic institutions ranging from zero to 10 with zero indicating the absolute dictatorship and 10 indicating the ideal form of democracy. e Electoral Participation ab Poverty Incidence b Real GDP Per Capita 2.00 to 5.50 Voter turnout as indicated by the percentage of the voting age population who actually voted. 31.5 to 83.7 Percentage of the population that was poor using the international poverty line of $1/day purchasing power parity 3.82 to 49.63 146 to 921 Trade including import and export as a percentage of GDP. b 12.50 to 88.64 Total population. a 3.69 to 9.10 0 to 1 0 to 9 Gross domestic product per capita in 2000 US$. b International Trade Population Value range 0 to 1 b 14.6 to 1064.4 c d e Sources: WIDER (2005); World Bank (2006); Freedom House (2005a); Polity IV Project (2005); IIDEA (2006) Tables Table 1. Measures of Democracy Period Political and Civil Liberties 1980s 1990s 2000-2003 Democratic Institutions 1980s 1990s 2000-2003 Inclusive Democracy 1980s 1990s 2000-2003 Bangladesh Pakistan Sri Lanka Country a Average Population b Average India Nepal 3.35 4.80 4.25 5.50 4.75 5.50 4.30 4.65 4.13 3.35 3.55 2.50 4.40 3.85 4.63 4.18 4.32 4.20 5.06 4.63 5.02 0.00 5.40 6.00 8.00 8.50 9.00 1.80 5.20 4.00 1.60 7.00 0.00 6.00 6.00 6.75 3.48 6.42 5.15 6.49 7.96 7.64 0.217 0.713 0.653 0.951 0.855 1.000 0.457 0.687 0.536 0.295 0.589 0.080 0.677 0.589 0.750 0.520 0.685 0.604 0.807 0.809 0.857 Note: a Simple (unweighted) average across five countries b Average weighted by the pouplation in different countries 31 Table 2. Measures of Inequality Period Bangladesh Gini Index (Coefficient) 1980s 1990s 2000-2003 80/20 Consumption Ratio 1980s 1990s 2000-2003 Economic Inequality 1980s 1990s 2000-2003 India Nepal Pakistan Sri Lanka Country Averagea Population Averageb 0.268 0.321 0.319 0.312 0.311 0.360 0.300 0.426 0.472 0.326 0.320 0.306 0.341 0.332 0.276 0.305 0.327 0.347 0.309 0.325 0.351 3.78 4.83 4.60 4.60 4.45 5.78 4.34 7.63 9.10 6.33 5.58 4.33 5.35 5.07 4.05 4.73 5.26 5.57 4.62 4.70 5.55 0.024 0.238 0.228 0.222 0.292 0.433 0.233 0.673 0.948 0.443 0.302 0.176 0.336 0.271 0.073 0.251 0.355 0.372 0.225 0.297 0.389 Note: a Simple (unweighted) average across five countries b Average weighted by the pouplation in different countries Table 3. Fixed Effects Regressions of Democracy (N=120) Variables Economic inequality Democracy I 0.226 Democracy II Liberties Institutions * (0.108) Gini 80/20 consumption 10.126 ** 28.848 ** 112.978 ** (1.413) (5.303) (16.269) -0.321 ** (0.050) Poverty incidence 0.008 ** (0.003) Real GDP PC 0.001 ** (0.000) Constant -0.041 0.018 ** (0.003) 0.001 ** (0.000) -1.861 ** -1.002 ** (0.189) (0.580) 0.065 ** (0.011) 0.002 0.147 ** (0.032) * (0.001) -2.636 -3.292 ** 0.009 ** (0.002) * -22.979 ** (0.156) (0.290) (1.090) (3.342) R 0.057 Note: 1) Values in parentheses are standard errors 2) * p<0.05, ** p<0.01 0.408 0.310 0.443 2 32 Table 4. Fixed Effects Regressions of Inequality (N=120) Variables Inequality I Inclusive democracy squared Inequality II 80/20 Gini 0.109 (0.162) Political and civil liberties -0.088 (0.119) 0.026 0.076 (0.017) (0.037) (0.001) 0.001 0.006 0.051 0.001 (0.006) (0.006) (0.015) (0.001) Electoral participation -0.001 * (0.000) Trade Constant R -0.009 (0.077) Democratic Institutions Real GDP PC -0.361 ** 0.020 ** -0.001 0.015 (0.004) * -0.006 ** (0.000) (0.001) * 0.081 ** (0.012) 0.004 ** <-0.001 ** (0.000) 0.003 ** (0.005) (.006) -0.037 0.079 (0.266) (0.287) (0.741) (0.026) 0.347 0.384 0.191 0.274 2 * 2.598 ** (0.000) 0.258 ** Note: 1) Values in parentheses are standard errors 2) * p<0.05, ** p<0.01 33 Table 5. Three Stage Least Square Regressions of Democracy and Inequality (N=120) Unweighted I Variables Economic inequality Democracy Inequality 0.476 ** Weighted I Democracy 0.428 (0.150) Inequality Unweighted II Democracy Weighted II Inequality Democracy Inequality * (0.212) Inclusive democracy squared 0.185 ** 0.031 (0.060) (0.039) Gini 10.111 ** 8.613 ** (1.358) 80/20 consumption (1.755) -0.315 ** -0.250 ** (0.048) (0.059) Political and civil liberties -0.050 ** -0.018 (0.019) Democratic Institutions (0.012) 0.018 ** 0.002 (0.006) Electoral participation 0.002 0.010 ** (0.002) Poverty incidence 0.007 * 0.009 ** (0.003) Real GDP PC 0.001 ** (0.000) Trade (0.000) 0.001 (0.000) 0.016 ** <-0.001 ** (0.000) 0.012 ** (0.004) 0.017 ** (0.003) (0.003) 0.001 ** (0.000) -0.001 ** (0.000) 0.016 ** (0.002) * (0.002) 0.017 ** (0.004) -0.001 ** 0.006 (0.002) (0.004) 0.001 * <-0.001 ** (0.000) 0.015 ** (0.002) (0.000) 0.015 ** (0.002) (0.002) Countries (Ref. = Bangladesh): India 0.242 ** (0.071) Nepal Pakistan 0.190 ** (0.028) 0.087 -0.031 -0.125 -0.088 -0.125 (0.063) (0.152) (0.067) (0.062) -0.375 ** -0.015 0.218 ** (0.086) -0.378 ** (0.086) -0.334 ** (0.077) 0.100 (0.135) 0.280 ** (0.056) -0.648 ** (0.071) -0.149 (0.046) * * (0.069) 0.234 ** (0.088) -1.887 ** 0.098 (0.061) 0.203 ** (0.031) -0.074 -0.151 -0.106 (0.060) (0.126) (0.067) 0.259 ** (0.072) -0.370 ** (0.084) -0.110 -0.174 * (0.080) 0.252 * (0.127) -1.666 ** 0.319 ** (0.053) -0.650 ** (0.072) -0.013 -0.148 0.005 (0.137) (0.122) (0.183) (0.114) (0.272) (0.122) (0.338) (0.096) 0.494 0.649 0.662 R Note: 1) Values in parentheses are standard errors 2) * p<0.05, ** p<0.01 3) For weighted models: Weighting variable = Total populaiton 0.770 0.662 0.694 0.720 0.780 2 -0.718 ** 0.202 ** (0.062) -0.086 (0.102) Constant 0.213 ** (0.062) (0.084) (0.079) Sri Lanka 0.159 ** (0.049) -0.759 ** 34