VIRGINIA JOURNAL BARZUZA

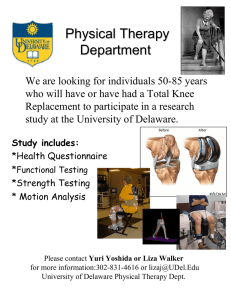

advertisement