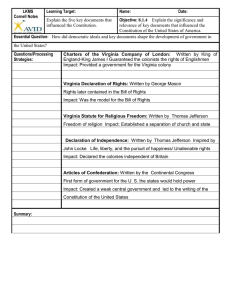

constitutional scholar: iDEas anD initiativEs

advertisement