Document 14104901

advertisement

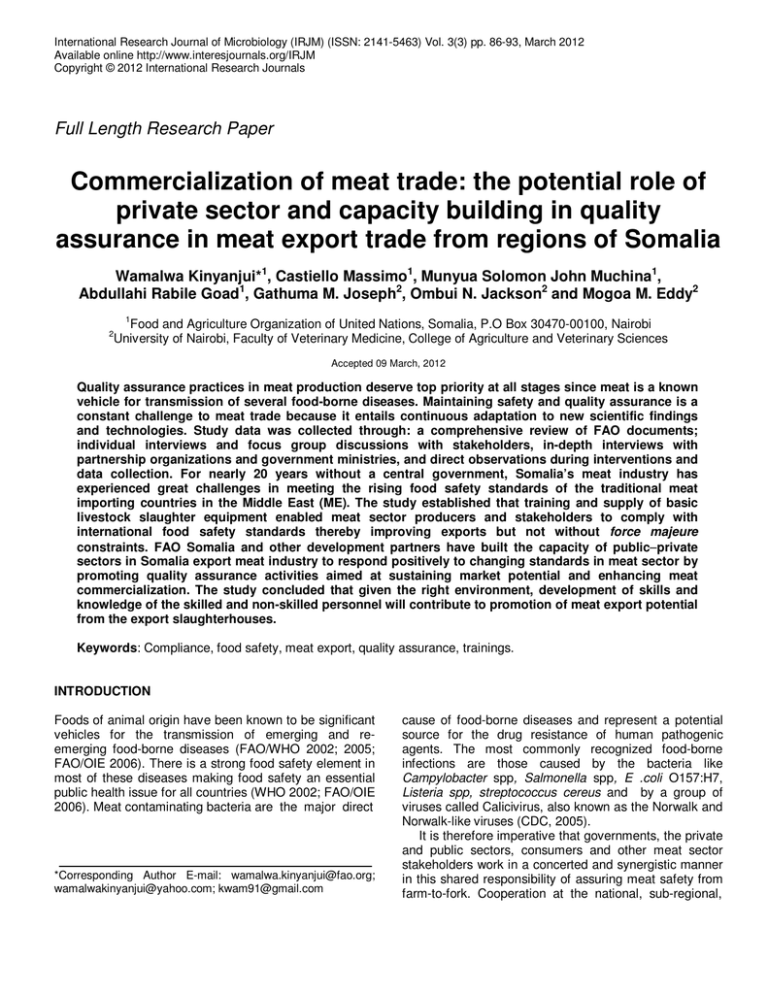

International Research Journal of Microbiology (IRJM) (ISSN: 2141-5463) Vol. 3(3) pp. 86-93, March 2012 Available online http://www.interesjournals.org/IRJM Copyright © 2012 International Research Journals Full Length Research Paper Commercialization of meat trade: the potential role of private sector and capacity building in quality assurance in meat export trade from regions of Somalia Wamalwa Kinyanjui*1, Castiello Massimo1, Munyua Solomon John Muchina1, Abdullahi Rabile Goad1, Gathuma M. Joseph2, Ombui N. Jackson2 and Mogoa M. Eddy2 1 Food and Agriculture Organization of United Nations, Somalia, P.O Box 30470-00100, Nairobi University of Nairobi, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, College of Agriculture and Veterinary Sciences 2 Accepted 09 March, 2012 Quality assurance practices in meat production deserve top priority at all stages since meat is a known vehicle for transmission of several food-borne diseases. Maintaining safety and quality assurance is a constant challenge to meat trade because it entails continuous adaptation to new scientific findings and technologies. Study data was collected through: a comprehensive review of FAO documents; individual interviews and focus group discussions with stakeholders, in-depth interviews with partnership organizations and government ministries, and direct observations during interventions and data collection. For nearly 20 years without a central government, Somalia’s meat industry has experienced great challenges in meeting the rising food safety standards of the traditional meat importing countries in the Middle East (ME). The study established that training and supply of basic livestock slaughter equipment enabled meat sector producers and stakeholders to comply with international food safety standards thereby improving exports but not without force majeure constraints. FAO Somalia and other development partners have built the capacity of public− −private sectors in Somalia export meat industry to respond positively to changing standards in meat sector by promoting quality assurance activities aimed at sustaining market potential and enhancing meat commercialization. The study concluded that given the right environment, development of skills and knowledge of the skilled and non-skilled personnel will contribute to promotion of meat export potential from the export slaughterhouses. Keywords: Compliance, food safety, meat export, quality assurance, trainings. INTRODUCTION Foods of animal origin have been known to be significant vehicles for the transmission of emerging and reemerging food-borne diseases (FAO/WHO 2002; 2005; FAO/OIE 2006). There is a strong food safety element in most of these diseases making food safety an essential public health issue for all countries (WHO 2002; FAO/OIE 2006). Meat contaminating bacteria are the major direct *Corresponding Author E-mail: wamalwa.kinyanjui@fao.org; wamalwakinyanjui@yahoo.com; kwam91@gmail.com cause of food-borne diseases and represent a potential source for the drug resistance of human pathogenic agents. The most commonly recognized food-borne infections are those caused by the bacteria like Campylobacter spp, Salmonella spp, E .coli O157:H7, Listeria spp, streptococcus cereus and by a group of viruses called Calicivirus, also known as the Norwalk and Norwalk-like viruses (CDC, 2005). It is therefore imperative that governments, the private and public sectors, consumers and other meat sector stakeholders work in a concerted and synergistic manner in this shared responsibility of assuring meat safety from farm-to-fork. Cooperation at the national, sub-regional, Kinyanjui et al. 87 regional and international levels provides opportunities for synergy and maximized benefits for improved human health and economic development both at domestic and export levels (FAO /WHO 2005). The demand for internationally high standards of animal health set by the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) (OIE 2007), food safety standards by Codex Alimentarius Commission (CAC) of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and the World Health Organization (WHO) (CAC 2005) and the Sanitary and Phytosanitary Standards (SPS) agreement by the World Trade Organization (WTO) (Weiler, 2004; Thomson et al., 2004) that are being adopted by the Gulf Cooperative Council (GCC) countries (GCC countries include Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Bahrain, Kuwait and Oman) of the Middle East (ME) which are the traditional importers of Somali chilled carcasses, present a challenge for Somalia meat sector, bearing in mind that the country has been without a functional central government since 1991. In 2009, Puntland, an autonomous state of Somalia applied for membership of Codex Alimentarius Commission, the body that regulates food safety standards (CAC 2010) In addition, export trade in live livestock had interruptions with vicious cycle of bans on perceived outbreak of transboundary animal diseases (TADs) leading to enormous losses in terms of revenue. The latest of this ban was in 2000 on perceived outbreak of Rift Valley Fever (RVF) which led to heavy economic losses yet Somalia did not have the capacity to contest the bans due to lack of a functional government (Holman 2002) . Data collected in 2008 from four of the five operating export slaughterhouses showed an export figure of 467,273 chilled small ruminant carcasses from Mogadishu Modern, Mubarak I, Mubarak II and H-foods export slaughterhouses (FAO Somalia, 2010; FSNAU, 2010) earning the slaughterhouses a profit of USD 2, 803, 638 according to profit margin of USD 6 per carcass of 6-8 kg as per livestock value chain analysis report of Muthee 2012. No data was collected from Beletweyne export slaughterhouse. To mitigate the high food safety standard requirements being adopted by GCC countries and circumvent the frequent live livestock trade bans, the private sector in Somalia established five export slaughterhouses that started exporting chilled carcasses of small ruminants which do not present risks of disease transmission to importing countries. Capacity building and training of slaughterhouse workers and management personnel of these slaughterhouses was viewed as an important aspect for production of high quality meat. According to FAO 2004, training of meat producers and livestock traders is vital to achieving production of high quality and safe meat with low levels of bacterial contamination and drug residues. Furthermore, wamalwa et al., 20011 has shown that training is an integral part of the foundation of knowledge, skills and technology transfer as it is crucial and a pre-requisite for implementation of food safety and quality assurance programmes that are designed to pragmatically mitigate the risk of substantial levels of bacterial, chemical and physical contamination of foods of animal origin. Moreover, Castiello et al., 2011 highlights that intervention through capacity building in addition to livestock disease surveillance, vaccinations, treatments, fodder production and establishment of water catchments along livestock trade routes is important for livestock to have good body conditions thereby promoting livestock exports. A good livestock body condition contributes to quality meat that is on demand in importing countries of the Middle East amidst stiff competition from other countries that export meat there. This paper describes efforts by FAO Somalia and other development partners to build the capacity of both the private and public meat sector stakeholders in North Western and North Eastern regions of Somalia to be more responsive to the changing food safety standards and demands for livestock and livestock products, of the traditional markets in the ME and other emerging markets. Study site The study was concentrated in the peaceful North Western (Somaliland) and North Eastern (Puntland) states of the expansive Somalia republic for a period of 2 years from September, 2007-September, 2009 when the slaughterhouses were fully operational. The study sites were H-foods (Burao district) and Mubarak II (Galkayo district) export slaughterhouses in Somaliland and Puntland respectively. However, some secondary data where possible was gathered from the remaining three export slaughterhouses (Mogadishu modern and Mubarak I and Beletweyne) located in Central and Southern Somalia that is embroiled in continuing civil conflict. DATA COLLECTION METHODOLOGY This involved reviewing of secondary data in FAO’s and development partners database. Primary data was collected through interviews with focus group discussions (abattoir workers), key informants, and direct observations and transect walks around the export slaughterhouses. The main stakeholders interviewed included export meat traders (SOMEAT) representatives, slaughterhouse workers, and Cooperazione Internazionale (COOPI), Veterinaires sans Frontiers Germany (VSF-G) and Ministry of Livestock staff involved in the interventions as shown in table 1 below. The questions were structured in a closed manner (yes/no) 88 Int. Res. J. Microbiol. with limited options of other and explain to maintain consistency of the outcome (Wesonga et al., 2010). RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS Questionnaire administration Data on interventions by FAO and other implementing partners was collected using a standard questionnaire. The questionnaires were administered in two parts; to the staff of the implementing partners and sub-contracted parties that carried out the trainings and other activities and to slaughterhouse managers and randomly selected slaughterhouse workers who benefitted from the trainings at the target slaughterhouses (Table 1). The questionnaires were administered in English and translated into Somali language by the local veterinarians where respondents had limited knowledge of English. The questions were designed to identify the type of Kinyanjui et al. 89 Table 1. Summary of key informants and slaughterhouse workers interviewed Implementing organization/ slaughterhouse FAO Somalia COOPI VSF-G Export slaughterhouses (H-foods & Mubarak II) Position of interviewee Kind of intervention Regional coordinator (1) and livestock consultant (1) Veterinary coordinator (1) Trainings, supply of tools/equipments, facilitation of learning tours Trainings Veterinary coordinator (1) Trainings, baseline microbiological analysis of meat swab samples Type of interventions received, by what organizations and impacts on meat quality and trade Type of training received and importance Managers (1 from each) General workers (10 from each) interventions that had been implemented by international organizations and evaluate any impact. the Export slaughterhouses Interventions and Findings Formation (SOMEAT) and support certificates. This promoted observance of high quality assurance for all export carcasses. of meat association To promote production of high quality and safe meat from slaughterhouses for export purposes from Somalia, FAO Somalia, and development partner organizations took an active role in building the capacity of the Somali Meat Trader’s Organization (SOMEAT). SOMEAT was supported by FAO and partners until it achieved the status of official registration in 2008 in Sharjah (UAE), one of the main importers of chilled small ruminant carcasses. The organization comprises of all proprietors of export slaughterhouses and major meat traders in Dubai and regions of Somalia and has offices in Dubai and owns the five export slaughterhouses in all regions of Somalia. FAO and partners supported the organization in collaboration with the Somali Government through trainings. In addition, selected members of each slaughterhouse were supported financially to undertake field study tours of the export markets in the Middle East as well as to training centres in the region (These included visits to Botswana Meat Commission, Kenya Meat Commission, and University of Nairobi; Kenya) to get practical lessons on standards of meat production. This enabled the organization to improve their meat production standards and hence better access to more GCC countries. As a result, SOMEAT enlisted the services of trained public veterinarians who provided meat inspection services and certification at all the five export slaughterhouses besides the normal inspection of all livestock destined for export before issuing export The five privately-owned operating export slaughterhouses in Somalia primarily exported chilled carcasses of sheep and goats to the Middle East, with the United Arab Emirates (UAE) being the main importer. Out of five abattoirs in the country, only three (Mubarak II, Beletweyne and H-foods) operated for eight to twelve months of 2009 during part of the study period. The Beletweyne abattoir stopped operations in September 2009 after exporting 28,020 carcasses because of insecurity incidents. H-foods similarly stopped operations because of limited demand for carcasses from the ME countries with no exports recorded in the last three months of 2009. From January 2009 to December 2009, carcass exports from Mubarak II were 44,105 and H-foods were 58,440 showing a decline of 43 percent and 61 percent respectively, compared to the same period in 2008. This decrease was attributed to increased competition over ME markets, low demand, lack of high quality animals and discontinuation of the meat transport commercial airline (DAALLO airlines) (The commercial airliner discontinued operations towards the end of 2009) from transporting meat from the operating slaughterhouse (FSNAU 2010). H-Foods export slaughterhouse exported few carcasses to ME countries using Juba airline in 2010 but discontinued shortly afterwards due to high operational costs (FSNAU 2010). Challenges Following concessions by UAE, the meat export market subsequently grew a great deal from 2006-2008, albeit 90 Int. Res. J. Microbiol. with challenges as interruptions of exports were occasioned by: • Poor quality livestock due to drought and climatic shocks (inadequate pasture and water); • Increased competition in ME markets by stronger exporters (e.g. Australia); • Low demand of carcasses especially in summer time when foreign workers are on holidays (FSAU 2009); • Under exploitation of the potential of Somali meat export market; • Stiff competition following the resumption of export of live livestock after the lifting of the trade ban in October 2009 by Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA); • Stiff competition in export of live livestock by the ports of Berbera and Bosasso following the construction and operationalization of quarantine holding grounds in the two ports by Gulf International Company from the ME; • Change of management of operations by DAALLO Airlines which was the only means of transport of chilled carcasses from all the export slaughterhouses in Somalia to ME countries; • Temporary ban of cargo from Somalia to KSA after two explosives were found on 2 planes destined for America from Yemen complicated the situation. Carcasses were air freighted to Oman then transported by refrigerated trucks to United Arab Emirates (UAE). The quality of most carcasses deteriorated by the time of reaching the destination market. Trainings, supply of basic slaughter equipments and regulations The human resource development focused on training; both technical and non-technical personnel working in the export slaughterhouses. They were trained in food safety and quality assurance programs including: Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP), Good Hygiene Practices (GHP), Standard Operating Procedures (SOP), Sanitary Standard Operating Procedures (SSOP), Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP) principles, sound slaughtering techniques, safe recovery of hides and skins and carcass traceability. FAO Somalia and implementing partners in collaboration with government authorities supported capacity building activities of technical, non-technical and management staff of the export slaughterhouses in meat safety and quality assurance practices. The technical staff trained included meat inspectors, veterinarians (public and private), electricians, municipal staff (hygiene and sanitation) and management personnel while nontechnical personnel included livestock stickers, flayers, slaughterhouse cleaners, meat transporters and general cleaners around the slaughterhouse. Between 80-92% of each export slaughterhouses’ workers were trained in their respective tasks and responsibilities from 2007 to 2009 as indicated in table 2. The target slaughterhouses were supplied with basic livestock slaughter equipments like stainless steel knives, hooks and receptacles, sharpening steels, protective gear (gumboots, white coats, overalls, aprons, caps, chin masks and gloves for meat handlers). The non-veterinary workers and the management personnel who acquired skills and knowledge in meat quality assurance programs diligently complied with international food safety standards until the slaughterhouses stopped operations due to force majeure constraints or circumstance beyond the control of the meat exporters like a commercial airline relied upon for meat export suspending operations and ban of cargo export to KSA. Below are a few sample figures (Figure 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6) taken during FAO Somalia intervention activities between 2007-2009 illustrating the meat production chain in the export oriented slaughterhouses of Somalia. Carcass exports From the carcass export figures from table 3 below, carcass exports from H-Foods export slaughterhouse increased by 210% between 2007 and 2008 when FAO Somalia and development partners initiated the intervention. It was not the same case in Mubarak II export slaughterhouse because of frequent insecurity incidents during2008; the year on intervention. The conflict, in addition to drought in the region affected delivery of good quality livestock for slaughter in the slaughterhouse (FSNAU 2010) contributing to a decline in carcass exports of 52%. Regulations To support continued and sustainable production of high quality and safe meat that meets international standards, FAO Somalia provided financial assistance and facilitated the drafting of the Meat Inspection and Control Act in 2008. The legal framework, regulations and laws once passed by respective parliaments and enforced, will instil a measure of control over the production and marketing of meat, both locally and internationally. This will promote quality assurance, safety and suitability of meat for export and domestic purposes, guaranteeing sustainable export markets once alternative meat transport means will be availed. However, meat production services are currently governed by the regulations that were established before the collapse of the former regime. Beneficiaries of the interventions The intervention activities by FAO Somalia aimed at increasing the competitiveness of the Somalia meat Kinyanjui et al. 91 Figure 1. Sheep and goats in pens ready for slaughter Figure 3. Final carcass washing Figure 5. Shrouded carcasses in chiller Figure 2. Slaughter process Figure 4. Marked inspected carcasses before shrouding Figure 6. Refrigerated meat transport truck Source: Figures; Dr. Wamalwa Kinyanjui, FAO Somalia) industry and enhanced opportunities within the pastoralist production system. Moreover production of high quality meat safeguards the health of consumers at the export markets increasing its competiveness. Furthermore, operators in the slaughterhouses under intervention benefitted from protection from public health hazards as they worked within the meat production chain. The benefits trickled down to pastoralists through better livestock selling prices and high demand. For livestock traders, it led to increased sales and better prices. The abattoir workers benefitted through job security and better terms of service, whereas meat exporters benefitted through increased sale quantities and reduced spoilage due to improved hygiene production standards. The professional animal health service providers benefitted through increased service demand and pharmaceutical drug dealers through increased sales and finally the government in terms of taxes. However, due to suspension of the only commercial air transport means of chilled carcasses to export markets in the ME, an alternative means is being sort so as to resume the exports that had tremendously 92 Int. Res. J. Microbiol. Table 2. Number of direct beneficiaries and types of trainings Slaughterhouse H-foods district) (Burao Mubarak II (Galkayo district) Type of training GMP, GHP, sound slaughtering techniques and traceability SSOP SOP GMP, GHP, sound slaughtering techniques and traceability SSOP SOP No. of workers 153 No. trained 143 % trained 126 40 50 102 26 33 81 40 50 32 40 94 Table 3. Exports of sheep and goats carcasses for the last five years Year 2010 2009 2008 2007 2006 2005 Mogadishu modern Not operational Not operational 80 240 16 717 112 912 Not operational Carcasses exported per year Mubarak I H-Foods (Nos.) Not operational 20 077 Not operational 58 440 172 739 136 269 186 049 64 900 277 250 183 350 Not operational 75 875 Mubarak II (Nos.) Not operational 44 105 78 025 118 579 (estimate) 128 537 23 619 Source: FAO Somalia 2010; FSNAU 2010; 2011) increased especially in H-foods slaughterhouse located in the peaceful North western Somalia. CONCLUSION The training of abattoir workers in food safety and quality assurance systems and support advanced to publicprivate partnership concept in the meat sector to promote quality control and certification and safeguard export market, served as an alternative remedy to live livestock export ban to ME countries. Capacity building of these parties went a long way in supporting compliance with quality assurance practices in meat production sector. This was apparent from increased carcass sales by 210% between 2007 and end of 2008 by H-foods export slaughterhouse. However, it was not the same for Mubarak II export slaughterhouse as the fruits of intervention were disrupted by the conflict in South Central Somalia that saw a lot of internally displaced persons flocking in and out of Galkayo town where the slaughterhouse is located. The rate of workers turnover at the slaughterhouse was high affecting application of skills and knowledge acquired through trainings. However, observation of quality assurance systems earlier introduced will enhance commercialization of meat trade both in domestic and offshore markets. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Disclaimer: The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the position of FAO. The designations employed do not imply FAO’s opinion concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area including the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Many actors enabled the successful accomplishment of this task; their invaluable support is very much appreciated. Investigators express their heartfelt appreciation to Luca Alinovi, the Officer incharge of FAO Somalia for accepting and allowing us total access to FAO facilities, documents and resources that proved handy in this research work. The project manager of the EU project (OSRO/SOM/004/E), Dr George Matete and the Sustainable Economic and Employment Programme (SEED) (OSRO/SOM/007/UK) manager, Dr Munyua Solomon, who sponsored the data collection, are highly acknowledged for the sponsorship. Mohammed Jama, Officer in-charge of FAO Hargeisa office, Somaliland, is highly recognized for his invaluable support. REFERENCES CAC (2010). Codex Alimentarius Commission member countries; http://www.codexalimentarius.net/web/member_info.jsp?iso3=SOM Kinyanjui et al. 93 Castiello M, Innocente S, Munyua SJM, Wamalwa K, Matete G and Njue S (2011). Sustainable Livelihood: Potential Role and Quality Assurance of Camel Export Trade in Somalia. http://www.internationalscholarsjournals.org/journal/ijas/December2011-Vol.1Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2005). National Centre for Emerging and National Zoonotic Diseases; http://www.cdc.gov/ncezid/ Codex Alimentarius Commission-(CAC) (2005. Code of Hygienic Practice for Meat; 2005.www.codexalimentarius.net/download/standards/0196/CXP058e.pdf FAO (2004). Good Practices for the Meat Industry. ftp://ftp.fao.org/docrep/fao/007/y5454e/y5454e00.pdf FAO Somalia (2010). Consultancy Report FAO/OIE (2006). Assuring Food Safety; the Complimentary Tasks and Foods of the World Organization for Animal Health and the Codex Alimentarius Commission. Rev. Sci. Tech. off. Epiz. 25 (2), 813-821. http://www.oie.int/doc/ged/D3565.PDF FAO/WHO (2002). Integrated Approaches to the Management of Food Safety throughout the Food Chain; FAO/WHO Global Forum of Food Safety Regulators, Marrakesh, Morocco, 20 - 30 Jan 2002 http://www.fao.org/docrep/meeting/004/y3680e/Y3680E07.htm FAO/WHO (2005). Assuring Food Safety and Quality in Small and Medium Size Food Enterprises; FAO/WHO Regional Conference on Food Safety for Africa, Harare, Zimbabwe, 3 -6 October 2005. ftp://ftp.fao.org/docrep/fao/meeting/010/j6022e.pdf Food Security and Nutrition Analysis (FSNAU) (2011). Post Deyr 2010/11; Technical Series Report No VI. 36; http://www.fsnau.org/downloads/FSNAU-Post-Deyr-2010-11Technical-Report.pdf Food security nutrition analysis unit (FSAU) (2009). Technical Series Report No V. 17, Issued March 4, 2009. www.fsnau.org Food security nutrition analysis unit (FSNAU) (2010). Technical Series Report No VI. 31, Issued March 3, 2010. www.fsnau.org Holman CF (2002). The socio-economic Implications of the Livestock Sector Ban in Somaliland; Consultancy report to famine early warning net/Somalia Muthee A (2012). The Somaliland Livestock Value Chain Analysis; A Proposal for Livestock Value Chain Development In Somaliland report for FAO OIE (2007). OIE Terrestrial Code; Standards on international trade in terrestrial animals and their products. http://www.oie.int/doc/ged/D6430.PDF Thomson G.R, Tambi E.N, Hargreaves S.K, Leyland T.J, Catley A.P, g.g.m. Van‘t KGGM, Penrith M (2004). Shifting paradigms in international animal health standards: the need for comprehensive standards to enable commodity-based trade. http://www.eldis.org/fulltext/shiftingparadigms.pdf Wamalwa K, Massimo C, Ombui JN, Gathuma J (2011). Capacity Building: Benchmark for Production of Meat with Low Levels of Bacterial Contamination in Local Slaughterhouses in Somaliland: Tropical Animal Health and Production: Volume 44, Issue 3 (2012), Page 427-433; http://www.springerlink.com/content/gp601134172u235m/ Weiler JHH (2004). Risk Regulation under the WTO SPS Agreement: Science as an International Normative Yardstick? http://centers.law.nyu.edu/jeanmonnet/papers/04/040201.pdf Wesonga FD, Kitala PM, Gathuma JM, Njenga MJ, Ngumi PN (2010). An assessment of tick-borne diseases constraints to livestock production in a smallholder livestock production system in Machakos District, Kenya. Livestock Res. Rural Dev. J. 22 (6) 2010. http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd22/6/weso22111.htm WHO (2002). Future Trends in Veterinary Public Health; WTO technical report series 907. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/trs/who_TRS-907.pdf