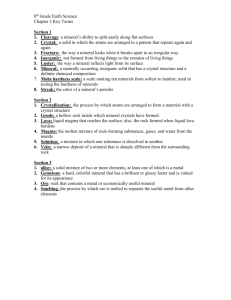

STABLE SUPPLY OF MINERAL RESOURCES

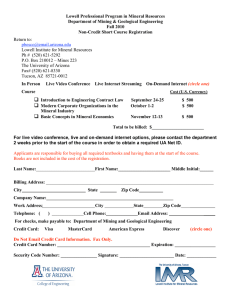

advertisement