Document 14092771

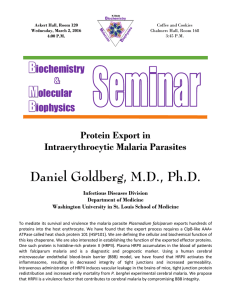

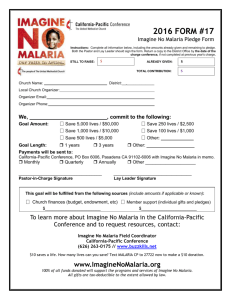

advertisement