Ross Notes 2015-2016 Our Town

advertisement

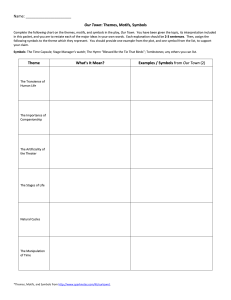

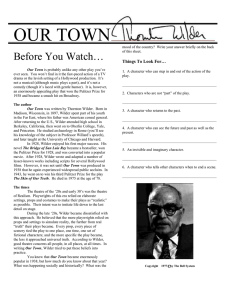

Ross Notes 2015-2016 Our Town Background: Wilder himself lived all over the country and traveled all over the world. He was a highly educated, massively innovative literary genius with insight into the human condition that was virtually unparalleled in playwrights of his era. Perched between two wars, the world was in a precarious position in 1938 with the rise of Nazi Germany. The United States was nine years into the Great Depression. When people spent money on theatre, they generally wanted to escape from their depressing lives. The theatre of the time found great success in staging lavish productions that whisked people away into other worlds, other eras, and other people’s lives. Wilder did the opposite. He stripped the stage bare and put ordinary life on display, inviting his audience, not to escape from their lives, but to enter into them more fully. He found enough significance in mundane, daily life events to engage his audience in celebrating what we already have during a period of uncertainty that the audience understood, having lived through the Great War. Wilder also likes to juxtapose the very large—from archeological finds from the distant past to the “Mind of God” in eternity—with those small, seemingly insignificant moments that make up that vast expanse. He uses the scope of time as both his backdrop and his canvas, and it’s plenty large enough for each. Wilder’s Stage Manager is a kind of Greek chorus, drawing the audience’s attention to characters, the imaginary set, and most of all, theme, because it is theme that we take back into our daily lives; it is theme that changes us. Our Town is one of the most brilliantly nuanced literary masterpieces I’ve ever studied. Look for the nuances, notice the little things, pay attention to patterns, examine the people pantomiming actions, and invest your attention into figuring out what they are doing. There is so much “under the radar” in this play that if you don’t pay attention, as in life, you’ll find that you’ve missed it all. Wilder has a reason for every detail he includes. I’ve found some of them, but I find more each year I study this beautifully simple, profound tribute to ordinary life. His call to us is to stop for a moment, for about three acts’ worth or so, and savor the simple, notice the small, and celebrate the unlikely miracle that each of our lives really is. Act I The audience in 1938 would have been freaked out entering an auditorium with a bare stage, seeing some guy up there setting up tables and chairs as if he were a crew member, and then talking straight to the audience. “This play is called Our Town.” Well, yes, that’s what it would say on their ticket stub. The introduction of the characters using letters of the alphabet—I think—was probably intended as a sort of run through of the credits, which in old movies generally happened in the beginning of the movie. They are in the form of variables, able to be changed for each different production. I’m not sure why he includes the coordinates, but I’ve been told that they aren’t precisely in New Hampshire. “The morning star always gets wonderful bright the minute before it has to go, doesn’t it?” There are 3 people in the play who are characterized as “bright”—not intelligent, not smart, not scholarly, but bright—Joe Crowell, Emily, and Wally. Look to see what happened to Joe Crowell. He died young in the war before he could ever use the prestigious education he’d earned from MIT. His star is awfully “bright” and his star “has to go, doesn’t it?” Uh oh. What do the following lines mean in reference to women of that time period? Had things changed by 1938? “…I think if a person starts out to be a teacher, she ought to stay one.” (9) “Women vote indirect.” (23) War: When Wilder has the Stage Manager casually mention Joe Crowell’s death in the war after all of the education he was never able to use, what message do you think he’s presenting about war? It’s worth thinking about. Funny that the hobbies of both dads in the play have to do with war—Dr. Gibbs is apparently a great expert in the Civil War while Mr. Webb’s interest lies in Napoleon, the great French general who had been dubbed “The Monster” during his reign. For both gentlemen, it’s merely a pastime, but for Joe Crowell, who during the scope of Act I seems to have a long and productive life ahead of him, war proves to be the end of all of his dreams. Look for other references to war in Act III. The town’s name is Grover’s Corners, plural. It’s significant, tying in with a beautiful line in Act III. The Gibbs and Webb families are quite similar and their names are easily confusable. This is deliberate. We are very much like our neighbors in certain ways. Look for them. Take a look at the different things Wilder uses in Mr. Webb’s response to the woman who asks about the cultural sentiment in Grover’s Corners. Handel’s “Largo” is not nearly as well-known as Handel’s “Messiah”—that’s the one with “The Hallelujah Chorus” at the end—but Wilder chooses the “Largo”—which means “slow.” Perhaps that’s how we are to live our lives, slowly so we don’t miss anything. Whistler’s “Mother” isn’t “The Mona Lisa” or the Madonna or a queen—it’s the artist’s mom in a rocking chair! The time capsule in the cornerstone of the new bank going up in Grover’s Corners has some interesting things planned for it. The Stage Manager says they will include The New York Times as well as the Grover’s Corners Sentinel. He also has a copy of the entire canon of Shakespearean plays as well as the play Our Town. [Mentioning the play as part of the play, a device known as ‘metadrama’, blurs the lines between the audience and the actors, between our lives and what we see on stage.] Notice that the Stage manager first mentions a big, important newspaper and then a small local one; he mentions the dramas of the premier playwright in the English language and then Wilder's humble offering. Each is equally important now, and presumably will still be in one or two thousand years. All of the ideas for the cornerstone (think about what the symbol means) are documents, and all but one tell stories. There’s both non-fiction and fiction, but the one thing that the Stage Manager clearly thinks will contain the most pointed truths about life is Our Town. Notice he says that the people who dig it up will know more than the Treaty of Versailles and the Lindbergh flight. I don’t know that more is meant strictly in the sense of something additional. Here it could mean more significant because it reflects the more common elements of ordinary people’s lives. Lindbergh’s reference—The entire audience would associate that reference not only with the first solo trans-Atlantic flight, but also with the horror of the Lindbergh kidnapping. One minute he’s there and the next he isn’t. They kiss him goodnight, the nanny takes him upstairs and puts him to bed, and they never see him again. No amount of superstardom or grandiose accomplishments can restore him to his family. Appreciate what we have while we can. I’d bet Lindbergh would’ve traded his all of his fame and glory to have his son back, but that isn’t an option. Pay attention. We do not know what the future holds. Notice how Mrs. Gibbs longs to travel, especially to see Paris. This is so unlike her homebody, workaholic husband who gives excuses not to take a break from his practice (except to indulge his own hobby, the Civil War). It’s probably unlike a lot of Grover’s Corners, which, as a small town, may be considered provincial. Notice, though, that Rebecca Gibbs is NOT one of the young people who settles down there after she graduates. We can’t tell how she meets her husband, but regardless of where he starts out, he winds up in Canton, Ohio. The Stage Manager tells us that Mrs. Gibbs goes out to visit her. He doesn’t say that she and her husband go out. It’s likely that Dr. Gibbs gave his wife a kiss goodbye, put her on the train to Canton, and never saw her again. Sounds a little like Lindbergh, doesn’t it? Remember that his wife died of pneumonia. It’s not clear if Dr. Gibbs could have saved her, but it’s a moot point anyway since he never went with her. Notice the preoccupation with the moon. Notice that Mrs. Gibbs tries to use the moonlight to soften up her husband to get him to agree to take a break. It doesn’t work. Emily stays up in the moonlight thinking about, oh, who knows, but it seems to make her happy… The Stage Manager mentions death right away in his monologue, even specifying the disposition of Mrs. Gibbs’ body—it’s in the grave up on the hill. I wonder why. Question: What do these things have in common? The only thing to do is not to notice it. Leave it alone Look the other way. Answer: They are all reactions to Simon Stimson’s scandalous drinking, by Mrs. Gibbs, Dr. Gibbs, and Constable Warren. We know that there isn’t much drinking in the town—that’s been set up by Editor Webb’s answer to the Woman in the Balcony—so Simon Stimson’s behavior is bound to stand out. Mr. Webb is the only one who offers any kind of non-judgmental friendship that we can see. Mrs. Webb actually lies about the severity of his drinking in order to shut down Mrs. Soames’ gossip on the way home from choir practice. It is also interesting that we associate “troubles” with Simon Stimson as the catalyst for his heavy drinking. Right after Mr. Webb encounters the troubled Simon Stimson, he notices that his daughter is awake and wants to make sure that she doesn’t have any troubles on her mind. She’s all dreamy in the moonlight—no troubles—but her dad just needs to make sure. Then he lets her stay up as long as her mother doesn’t catch her at it, and he walks inside whistling “Blessed Be the Tie That Binds.” They have a good relationship, and Mr. Webb keeps those ties strong. I love “Art Thou Weary? Art Thou Languid?” as a hymn choice from Simon Stimson. He seems very much both, so it works contrary to the irony of “Blessed Be the Tie That Binds.” You do need to remember that hymn in relation to how Simon Stimson will “end.” It’s macabre genius. How many of these topics does Wilder touch on in Act I alone? birth education high school graduation marriage hobbies livelihood crime politics death Now, the first act is about a typical day-in-the-life, so why would he touch on all of these huge topics? Just saying…