Creating Capabilities

advertisement

Creating Capabilities

James Heckman

University of Chicago

and Human Capital and Economic Opportunity Working Group,

Institute For New Economic Thinking

RIETI

October 8th, 2014

This draft, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

2 / 122

.45

.5

Figure 1: Trends in Family Income Inequality in Japan

nsfers

d Tra

an

Taxes

.35

.4

Before

sfers

.25

.3

After Taxes and Tran

1985

1990

1995

Before Taxes and Transfers

After Taxes and Transfers

Year

2000

2005

2010

OLS Slope=0.005, p-value=0.000

OLS Slope=0.001, p-value=0.043

Source: Bradley J. Setzler (2014)

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

3 / 122

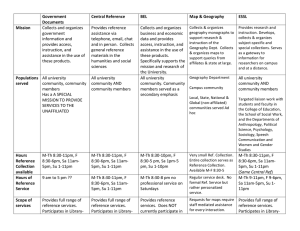

Measures of Wealth Inequality (NSFIE)

0.66

Equalized Net Financial Wealth (GINI)

0.64

0.62

0.6

0.58

0.56

0.54

0.52

1984

1989

1994

1999

2004

Source: Lise etal., 2014

Data: National Survey of Family Income and Expenditure (NSFIE)

Source: Lise et al., 2010

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

4 / 122

Poverty Rates in Japan

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

1985

1988

Poverty rate (%)

1991

1994

Child poverty rate (%)

1997

2000

2003

2006

2009

2012

Poverty Rate Single Parent (18-65) with Children Under 17

Source: Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions

Note: Poverty rate is calculated according to OECD guideline ( The poverty rate is the ratio of the number of people who fall below the poverty

line and the total population; the poverty line is here taken as half the median household income)

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

5 / 122

Figure 2: Percentage distribution of the number of Japanese households

by self-assessed living-conditions, for all the households and specific

households; Figure

2010

19: Percentage distribution of the number of households by self-assessed living-conditions, for all

the households and specific households

2010

Very comfortable

Very difficult

All households

Difficult

(59.4%)

Somewhat difficult

27.1

Somewhat comfortable

Normal

32.3

4.1

35.8

0.7

(51.5%)

Aged households

21.3

4.0

30.2

44.0

0.5

(65.7%)

Households with

children

3.8

31.0

34.7

0.3

30.1

(85.6%)

Mother-child

households

0.5

50.5

0%

10%

20%

35.1

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

13.9

80%

90%

100%

Source: FromFrom

Ministry of Health,

Labour, and Welfare

Source

Ministry

of Health, Labour, and Welfare.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

6 / 122

A Basic Fact on Gender Inequality in Hourly Wage in Japan

Table 1: Gender Inequality in Employment Status and Hourly Wage

(2006 Wage Census in Japan)

Source Yamaguchi (2014).

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

7 / 122

Intergenerational Mobility and Inequality:

The “Gatsby Curve”

IGE: ln Y1 = α + βln Y0 + ε

|{z}

|{z}

Income of

parents

Italy

UK

USA

France

Japan

Germany

NZ

Sweden

Canada

Australia

Norway

Finland

Denmark

0

Intergen. Elasticity of Earnings (IGE)

.1

.2

.3

.4

.5

Income in current

generation

.2

.25

.3

Gini Coefficient, After Taxes and Transfers

Corak's Chosen IGE

.35

OLS Slope=2.05, p-value=.001

Source: Bradley J. Setzler (2014)

Note:

Inequality is measured after taxes and transfers.

Gini index defined on household income.

IGE measured by pre-tax and transfer income of individual fathers and sons.

•

•

•

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

8 / 122

.5

Figure 3: Changing to Pretax Family Income

USA

Intergen. Elasticity of Earnings (IGE)

.1

.2

.3

.4

Italy

UK

France

Japan

NZ

Canada

Norway

Germany

Australia

Sweden

Finland

0

Denmark

.34

.38

.42

Gini Coefficient, Before Taxes and Transfers

Corak's Chosen IGE

.46

OLS Slope=1.36, p-value=.093

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

9 / 122

The traditional approach to inequality is “alms to the poor”

or “redistribution.”

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

10 / 122

Skills are Major Determinants of Inequality

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

11 / 122

• A Strategy Based on Creating Capabilities:

Capabilities are “Capacities” or “Skills”

• Capabilities: The Capacities to Act and to Create

Future Capacities

Capabilities are defined as the real f reedoms people have

to achieve and the beings and doings that they value and

have reason to value

Sen, 1979, 1985, 1992; Nussbaum and Sen, 1993.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

13 / 122

Eight Broad Lessons from the Recent Research Literature on

Creating Capabilities

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

14 / 122

1. Multiple Skills

Multiple skills vitally affect performance in life across a variety of

dimensions. A large body of evidence shows that cognitive and

noncognitive skills affect labor market outcomes, the likelihood of

marrying and divorcing, the likelihood of receiving welfare, voting,

and health.

2. Gaps in Skills

Gaps in skills between individuals and across socioeconomic groups

open up at early ages for both cognitive and noncognitive skills.

Many measures show near-parallelism during the school years across

children of parents from different socioeconomic backgrounds, even

though schooling quality is very unequal.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

16 / 122

3. Capabilities Can Be Created by Investment

The early emergence of skill gaps might be interpreted as the

manifestation of genetics: Smart parents earn more, achieve more,

and have smarter children. A body of strong experimental evidence

shows the powerful role of parenting and environments, including

mentors and teachers in shaping skills.

Genes are important, but skills are not solely genetically determined.

The role of heritability is exaggerated in many studies and in

popular discussions. Genes need sufficiently rich environments to

fully express themselves. There is mounting evidence that gene

expression is itself mediated by environments. Epigenetics informs us

that environmental influences are partly heritable.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

17 / 122

4. Critical and Sensitive Periods in the Technology of Skill

Formation

There is compelling evidence for critical and sensitive periods in the

development of a child. Different capacities are malleable at

different stages of the life cycle. For example, IQ is rank stable after

age 10, whereas personality skills are malleable through adolescence

and into early adulthood. A substantial body of evidence from

numerous disciplines shows the persistence of early life disadvantage

in shaping later life outcomes. Early life environments are important

for explaining a variety of diverse outcomes, such as crime, health,

education, occupation, social engagement, trust, and voting.

5. Family Investments

Gaps in skills by age across different socioeconomic groups have

counterparts in gaps in family investments and environments.

Children from disadvantaged environments are exposed to a

substantially less rich vocabulary than children from more

advantaged families. At age three, children from professional

families speak 50% more words than children from working-class

families and more than twice as many compared to children from

welfare families. There is a substantial literature showing that

disadvantaged children have compromised early environments as

measured on a variety of dimensions. Recent evidence documents

the lack of parenting knowledge among disadvantaged parents.

Parenting styles in disadvantaged families are much less supportive

of learning and encouraging child exploration.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

19 / 122

6. Resilience and Targeted Investment

Although early life conditions are important, there is considerable

evidence of resilience and subsequent partial recovery. To our

knowledge, there is no evidence of full recovery from initial

disadvantage. The most effective adolescent interventions target the

formation of personality, socioemotional, and character skills through

mentoring and guidance, including providing information. This

evidence is consistent with the greater malleability of personality and

character skills into adolescence and young adulthood. The body of

evidence to date shows that, as currently implemented, many later

life remediation efforts are not effective in improving capacities and

life outcomes of children from disadvantaged environments. As a

general rule, the economic returns to these programs are smaller

compared to those policies aimed at closing gaps earlier.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

20 / 122

However, workplace-based adolescent intervention programs and

apprenticeship programs with mentoring, surrogate parenting, and

guidance show promising results. They appear to foster character

skills, such as increasing self-confidence, teamwork ability,

autonomy, and discipline, which are often lacking in disadvantaged

youth. In recent programs with only short-term follow-ups,

mentoring programs in schools that provide students with

information that improves their use of capacities have also been

shown to be effective.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

21 / 122

7. Parent-child/Mentor-child Interactions Play Key Roles in

Promoting Child Learning

A recurrent finding from the family influence and intervention

literatures is the crucial role of child-parent/child-mentor

relationships that “scaffold” the child (i.e., track the child closely,

encourage the child to take feasible next steps forward in his or her

“proximal zone of development,” and do not bore or discourage the

child). Successful interventions across the life cycle share this

feature. The child as an “emergent” system.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

22 / 122

8. High Returns to Early Investment

Despite the generally low returns to interventions targeted toward

the cognitive skills of disadvantaged adolescents, the empirical

literature shows high economic returns for investments in young

disadvantaged children. There is compelling evidence that

high-quality interventions targeted to the early years are effective in

promoting skills. This is a manifestation of “dynamic

complementarity”.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

23 / 122

Predistribution, Not Just Redistribution

A Comprehensive Understanding of Capability Formation

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

25 / 122

• To effectively produce capabilities, we should take a more

comprehensive approach to understanding the economics of

skill development.

• Need to formulate policies that clearly recognize what skills

matter, how they are produced and at what stage of the life

cycle it is most productive to invest, and how we should

prioritize public policy toward producing skills.

• Doing so avoids fragmented and often ineffective approaches to

public policy that miss the pervasive importance of skills.

• The skills problem is at the core of many social and economic

problems that plague societies around the world.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

26 / 122

Fragmented solutions are often not effective.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

27 / 122

Fragmented Solutions

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

28 / 122

Prevention, not just remediation.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

29 / 122

The Ingredients of Effective Capability Formation Strategies

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

30 / 122

Modern Understanding of Human Development

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

31 / 122

• The family lives of children are the major producers of

cognitive and socio-emotional skills.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

32 / 122

• Supplementing the family and its resources, engaging it in

enriching the life of the child, in supporting the child in school,

and in giving sound advice to children, are effective policies. So

are policies that enhance the skills of parents to be parents.

(i) If society intervenes early enough and in a consistent fashion

over the life cycle of a child, it can promote cognitive and

socioemotional capabilities, as well as the health and wellbeing

of children born into disadvantage.

(ii) Through multiple channels, these effects percolate across the

life cycle and across generations.

(iii) For example, high-quality early interventions reduce inequality

by promoting schooling, reducing crime, and reducing teenage

pregnancy.

(iv) They promote health and healthy behaviors.

(v) They also foster workforce productivity.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

33 / 122

(vi) These interventions have high benefit-cost ratios and rates of

return. They pass efficiency criteria that any social program

should be asked to pass.

(vii) Quality early childhood policies are among the rare social

policies that face no equality-efficiency tradeoff.

(viii) What is fair is also economically efficient.

(ix) Early interventions that build the capability base of children

have much higher economic returns than later remediation and

prevention programs, such as public job training, convict

rehabilitation programs, adult literacy programs, tuition

subsidies, or expenditure on police to reduce crime.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

34 / 122

• Universal ingredient of all successful interventions–by

families, schools, and mentors in the work place

• “Scaffolding”

• Monitoring and mentoring the child, taking stock of

where they are and taking them to the next step.

Interactions and interplay are at the heart of all

successful skill development approaches.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

35 / 122

The Importance of Cognitive and Character Skills

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

36 / 122

Table 2: The Big Five Domains and Their Facets: OCEAN

Big Five Personality Factor

Facets (and correlated trait adjective)

Openness to experience

Fantasy (imaginative)

Aesthetic (artistic)

Feelings (excitable)

Actions (wide interests)

Ideas (curious)

Values (unconventional)

Competence (efficient)

Order (organized)

Dutifulness (not careless)

Achievement striving (ambitious)

Self-discipline (not lazy)

Deliberation (not impulsive)

Warmth (friendly)

Gregariousness (sociable)

Assertiveness (self-confident)

Activity (energetic)

Excitement seeking (adventurous)

Positive emotions (enthusiastic)

Trust (forgiving)

Straight-forwardness (not demanding)

Altruism (warm)

Compliance (not stubborn)

Modesty (not show-off)

Tender-mindedness (sympathetic)

Anxiety (worrying)

Hostility (irritable)

Depression (not contented)

Self-consciousness (shy)

Impulsiveness (moody)

Vulnerability to stress (not self-confident)

Conscientiousness

Extraversion

Agreeableness

Neuroticism/Emotional Stability

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

37 / 122

Ever Been in Jail by Age 30, by Ability (Males)

Ever been in jail by age 30, by ability (males)

olarization

.15

rgument

kills

.10

ritical and

ensitive

eriods

Probability

vidence

.05

nvironment

ntuitive

stimates

lustration

.00

0 – 20

21 – 40

41 – 60

61 – 80

81 – 100

Percentile

ummary

Cognitive

Noncognitive

Note: This figure plots the probability of a given behavior associated with moving up in one ability distribution for someone after

integrating out the other distribution. For example, the lines with markers show the effect of increasing noncognitive ability after

integrating the cognitive ability.

Note: This figure plots the probability of a given behavior associated with moving up in one

ability distribution for someone after integrating out the other distribution. For example, the

lines with markers

the Stixrud,

effect and

of increasing

Source:show

Heckman,

Urzua (2006).noncognitive ability after integrating the

cognitive ability.

Source: Heckman, Stixrud, and Urzua (2006).

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

38 / 122

Probability of Being Single With Children

(Females)

Probability of being single with children

olarization

.10

gument

kills

.08

itical and

ensitive

eriods

nvironment

Probability

vidence

.06

.04

tuitive

stimates

ustration

.02

0 – 20

21 – 40

41 – 60

61 – 80

81 – 100

Percentile

ummary

Cognitive

Noncognitive

Note: This figure plots the probability of a given behavior associated with moving up in one ability distribution for someone after

integrating out the other distribution. For example, the lines with markers show the effect of increasing noncognitive ability after

integrating the cognitive ability.

Note: This figure plots the probability of a given behavior associated with moving up in one

ability distribution for someone after integrating out the other distribution. For example, the

lines with markers

theStixrud,

effectand

of Urzua

increasing

Source:show

Heckman,

(2006).noncognitive ability after integrating the

cognitive ability.

Source: Heckman, Stixrud, and Urzua (2006).

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

39 / 122

Probability of being a 4-year college graduate by age 30

Probability and

Confidence Interval (2.5-97.5%)

ii. By Decile of Cognitive Factor

iii. By Decile of Personality

1

1

0.8

0.8

0.6

0.6

0.4

0.4

0.2

0.2

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

Decile

7

8

9

10

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Decile

Notes: The data are simulated from the estimates of the model and our NLSY79 sample. We use the standard convention that higher deciles are associated with higher values of the variable.

The confidence intervals are computed using bootstrapping (200 draws).

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

40 / 122

The GED illustrates the power of non-cognitive skills

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

41 / 122

Figure 4: Distribution of Cognitive Ability by Educational Status (No

College Sample, All Ethnic Groups)

Dropout

GED

Secondary Graduate

Source: Reproduced from Heckman et al. (2011), based on data from the National

Longitudinal Survey of Youth, 1979 (NLSY79).

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

42 / 122

Figure 5: Hourly Wage Differences of GED Recipients and Traditional

Graduates Compared to Uncertified Dropouts—Ages 20–39

(b) Hourly Wage

0

2

4

6

8

10

Annual Earnings

Abil

5−29

Raw Abil

Raw Abil

Raw Abil

Raw Abil

Raw Abil

Raw Abil

30−34

35−39

20−24

25−29

30−34

35−39

.15

) Hours Worked

GED

(d) Employment

H.S.

+/− S.E.

0

.05

.1

Source: Reproduced from Heckman et al. (2014), which uses data from the National

Longitudinal Survey of Youth, 1979 (NLSY79).

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

43 / 122

Figure 6: Distribution of Non-Cognitive Skills by Education Group

Non-Cognitive Skill

Dropout

GED

Secondary Graduate

Source: Reproduced from Heckman et al. (2011), which uses data from the National

Longitudinal Survey of Youth, 1979 (NLSY79).

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

44 / 122

Evidence on Noncognitive Skills for Japan

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

45 / 122

Figure 7: Standardized Regression Coefficient associated with Years of

Schooling in Japan

Source: LEE SunYoun and OHTAKE Fumio, RIETI Discussion Paper Series 14-E-023, May

2014

Note: The figure displays standardized regression coefficient from multivariate of years of

schooling completed on the personality trait and parental education, controlling for age and

age-squared and gender. The darker rectangular bars are the estimates with the control of

parental educational background and the line bars represent robust standard errors.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

46 / 122

Figure 8: Standardized Regression Coefficient associated with Earnings in

Japan

Source: LEE SunYoun and OHTAKE Fumio, RIETI Discussion Paper Series 14-E-023, May

2014

Note: The figure displays standardized regression coefficient from multivariate of annual

income on the personality trait and ones own educational attainment, controlling for potential

experience and its squared, gender, occupation, type of employment, industry, company size,

and years of work experience at the current work place. The darker rectangular bars are the

estimates with the control of parental educational background and the line bars represent

robust standard errors.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

47 / 122

Figure 9: Adjusted R-2 associated with Earnings in Japan and the US

Source: LEE SunYoun and OHTAKE Fumio, RIETI Discussion Paper Series 14-E-023, May

2014

Note: Adjusted R 2 s for linear regressions for annual income (log). Total indicates the

Adjusted R 2 when Big 5, total years of schooling, and behavioral characteristics are all

included into the wage equation.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

48 / 122

• Can these traits be reliably measured?

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

49 / 122

Developing a More Comprehensive Measurement Systems:

A Task-Based Framework for Identifying and Measuring

Skills

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

50 / 122

Personality traits are the relatively enduring patterns of

thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that reflect the tendency

to respond in certain ways under certain circumstances.

(Roberts, 2009, 140)

• All psychological measures are performance on tasks

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

52 / 122

Figure 10: Determinants of Task Performance

Incentives

Effort

Character

Skills

Task

Performance

Cognitive

Skills

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

53 / 122

Figure 11: Decomposing Variance Explained for Achievement Tests and

Grades into IQ and Non-Cognitive Skills: Stella Maris Secondary School,

Maastricht, Holland

Source: Borghans et al. (2011).

Note: Grit is a measure of persistence on tasks (Duckworth et al., 2007).

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

54 / 122

Gaps Open Up Early

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

55 / 122

0

.5

Mean cognitive score

1

Trend in mean by age for cognitive score by maternal education

3

5

College grad

8

18

Age (years)

Some college

HS Grad

Less than HS

Each score standardized within observed sample. Using all observations and assuming data

missing at random. Source: Brooks-Gunn et al. (2006).

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

56 / 122

Rank onbehavior

Anti-Social

AverageAverage

percentilePercentile

rank on anti-social

score, by income

Behavior

Score,

by

Income

Quartile

quartile

ation

55

ent

and

ve

nment

Score Percentile

ce

50

45

40

35

30

e

25

tes

20

tion

4 Yrs

6 Yrs

8 Yrs

Age

ary

Lowest Income Quartile

Second Income Quartile

Third Income Quartile

Highest Income Quartile

10 Yrs

12 Yrs

Lexical Ability of Children by Annual Household Income

35

30

Vocabulary Scores

25

20

15

10

5

3 year olds

4 year olds

< 5million yen

5 to 9 million yen

5 year olds

>9 million yen

Source: recreated from Hamano 2010

Note: Lexical Ability is measured by Picture Vocabulary Test (PVT). PVT measure the

degree of development of language comprehension, in particular, basic “vocabulary

comprehension.” The test is used internationally and asks children to perform such tasks as

choosing the most appropriate picture from a set of four for a word given by the examiner.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

58 / 122

Figure 12: Mother’s educational attainment and level of academic ability,

Mathematics

Source: Akabayashi et al. (2013).

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

59 / 122

Figure 13: Family income and academic ability, Mathematics

Source: Akabayashi et al. (2013).

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

60 / 122

How to Interpret This Evidence

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

61 / 122

• Evidence on the early emergence of gaps leaves open the

question of which aspects of families are responsible for

producing these gaps.

• Is it due to genes?

• Family environments? Neighborhood and community effects?

• Parenting and family investment decisions?

• The evidence from a large body of research demonstrates an

important role for investments and family and community

environments in determining adult capacities above and beyond

the role of the family in transmitting genes.

• The quality of home environments by family type is highly

predictive of child success.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

62 / 122

“It is said that heaven does not create one man above or below

another man. Any existing distinction between the wise and the

stupid, between the rich and the poor, comes down to a matter of

education.” – Fukuzawa Yukichi

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

63 / 122

Variation in Family Environments

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

64 / 122

Mothers’ Speech and Child Vocabulary: Hart & Risley, 1995

Children enter school with “meaningful differences” in vocabulary

knowledge.

1. Emergence of the Problem

In a typical hour, the average child hears:

Family

Status

Welfare

Working Class

Professional

Actual Differences in Quantity

of Words Heard

616 words

1,251 words

2,153 words

Actual Differences in Quality

of Words Heard

5 affirmatives, 11 prohibitions

12 affirmatives, 7 prohibitions

32 affirmatives, 5 prohibitions

2. Cumulative Vocabulary at Age 3

Cumulative Vocabulary at Age 3

Children from welfare families:

Children from working class families:

Children from professional families:

500 words

700 words

1,100 words

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

65 / 122

Relation between the Mother's Education Beckground and her

Educational Awareness and Behavior (%)

Junior or Senior High School Graduate

Vocational College or Junior College

University or Graduate School

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Reads picture Takes the child

Provides

Talks to the Many books at Mother reads

story books to

to visit

breakfast for child about the

home

books

child

museums

the child every

news

day

Mother visits

museums

Parents are

aware that

children should

be exposed to

foreign cultures

Source: Hamano 2010

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

66 / 122

0.05

Proportion of Children in Family Type

0.10

0.15

0.20

0.25

0.30

Children Under 18 Living in Single Parent Households by Marital Status of Parent

1976

1980

1984

1988

Divorced

Widowed

1992

1996

Year

2000

2004

2008

2012

Married, Spouse Absent/Separated

Never Married/Single

Source: IPUMS March CPS 1976‐2012

Note: Parents are defined as the head of the household. Children are defined as individuals under 18, living in the household, and the child of the head of household. Children who have been married or are not living with their parents are excluded from the calculation. Separated parents are included in “Married, Spouse Absent” Category

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

67 / 122

Children Under 20 Living in Single Parent Households by Marital

Status of Single Mother (Japan)

8

7

6

Perventage

5

4

3

2

1

0

1998

2001

2004

Divorced

2007

Widowed

2010

2013

Unmarried

Source: Comprehensive Survey of Living Condition

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

68 / 122

Single Parent Households Among Households with Children under 20 in

Japan

8

7

6

Percentage

5

4

3

2

1

0

1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013

single mother

single father

Source: Comprehensive Survey of Living Condition

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

69 / 122

• Interpreting effects of family income: U.S. / Japan / Denmark

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

70 / 122

College attendance by AFQT and Family Income Quartiles (1997)

Source: Belley and Lochner (2007).

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

71 / 122

Figure 14: In Japan: Family income plays a key role in determining

students’ path following high school graduation

Percent of High School Graduates

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

72 / 122

An Informative Comparison: US vs. Denmark

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

73 / 122

High School Completion and College Attendance by Mother's Education Denmark and US

High School Completion

College Attendance

0.7

0.9

0.8

0.6

0.7

0.5

0.6

0.5

0.4

0.4

0.3

0.3

0.2

0.2

0.1

0.1

0

0

No High School

High School

Denmark

College

No High School

US

High School

Denmark

College

US

Source: Rasmus Landers

Note: Observation Denmark 33,954; CNLSY 3,268

Source:

James Heckman and Rasmus Landersø (2014).

Note: Observation Landersø Denmark 33,954; CNLSY 3,268.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

74 / 122

Figure 15: High school completion by mother’s education

Source: Rasmus Landersø (2014).

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

75 / 122

Figure 16: College attendance by mother’s education

Source: Rasmus Landersø (2014).

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

76 / 122

• What is the role for capabilities in explaining gaps?

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

77 / 122

Figure 17: Cognitive skills at age 15-16 and parental income / wealth

(a) CNLSY

(b) Denmark

Source: James Heckman and Rasmus Landersø (2014).

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

78 / 122

Figure 18: College attendance and parental income / wealth

(a) CNLSY

(b) Denmark

Source: James Heckman and Rasmus Landersø (2014).

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

79 / 122

Figure 19: High school completion by parental income and wealth — θC ,

θN,C

(a) CNLSY

(b) Denmark

Source: James Heckman and Rasmus Landersø (2014).

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

80 / 122

Figure 20: College attendance by parental income and wealth — θC ,

θN,C

(a) CNLSY

(b) Denmark

Source: James Heckman and Rasmus Landersø (2014).

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

81 / 122

Genes, Biological Embedding of Experience,

and Gene-Environment Interactions

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

82 / 122

DNA methylation and histone acetylation patterns in young and old twins

Methylation patterns in young and old twins

Manel Esteller

Source: Fraga, Ballestar et al. (2005).

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

83 / 122

Interventions

Early childhood interventions targeted to disadvantaged children are

effective in overcoming these gaps.

• They provide evidence against a purely genetic argument.

• These provide supplementary parenting for disadvantaged

children.

• A primary avenue through which they operate is personality and

noncognitive skills.

• Did not boost IQ.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

84 / 122

Cognitive Evolution through Time, Perry Males

Male Cognitive Dynamics

105

Treatment

100

95

IQ

90

85

Control

80

75

Treatment

79.2

94.9

95.4

91.5

91.1

88.3

88.4

83.7

Control

77.8

83.1

84.8

85.8

87.7

89.1

89.0

86.0

Entry

4

5

6

7

8

9

Age

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

10

85 / 122

Yet the Perry Program has a statistically significant annual rate of

return of around 6%–10% per annum—for both boys and girls—in

the range of the post–World War II stock market returns to equity

in the U.S. labor market, estimated to be 6.9%.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

86 / 122

• It worked primarily through noncognitive and character

channels.

Early interventions reducing problem behavior lower the probability

of engaging in unhealthy behaviors in adulthood.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

87 / 122

.8

.4

.6

density

.6

.4

.2

.2

0

0

density

.8

1

1

Figure 21: Mechanisms: Externalizing Behavior, Males

2

2.5

3

3.5

(a) Control

4

4.5

5

2

®

2.5

3

3.5

4

(b) Treatment

4.5

5

®

Data: Perry Preschool Program.

Source: Heckman, Pinto, Savelyev (2013).

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

88 / 122

Figure 1: Decompositions of Treatment Effects,

Males of Treatment Effects, Males

Decomposition

zation

ment

CAT total*, age 14(+)

Employed, age 19 (+)

Monthly Income, age 27 (+)

nce

No tobacco use, age 27 (+)

al and

tive

ds

# of adult arrests, age 27 (-)

onment

ve

ates

ation

mary

Jobless for more than 2 years, age 40 (-)

Ever on welfare (-)

Total charges of viol.crimes with victim costs, age 40, (-)

Total charges of all crimes, age 40 (-)

Total # of lifetime arrests, age 40 (-)

Total # of adult arrests, age 40 (-)

Total # of misdemeanor arrests, age 40 (-)

Total charges of all crimes with victim costs, age 40 (-)

Any charges of a crime with victim cost, age 40 (-)

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

Cognitive Factors

Socio-Emotional State

Personal Behavior

Other Factors

70

80

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

90

100%

89 / 122

Long-Term Health Effects of Perry: Males

The Abecedarian Intervention

Source: Campbell, Conti, Heckman, Moon, Pinto, and Pungello (2014)

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

91 / 122

ABC Health Effects Mid 30s: Males

Data: Abecedarian Program. Source: Campbell et al. (2014)

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

92 / 122

ABC Mechanisms: IQ

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

93 / 122

Attachment, Engagement

Toward a Deeper Understanding of Parenting and Learning

• In both Perry and ABC (and many other interventions) a main

channel of influence is on parent-child interactions.

• Enhanced attachment and engagement of parents.

• This has important implications for how we model family

influence.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

94 / 122

Dewey:

“Successful schools do what successful parents do”

—Dewey (1915)

Recent analyses would change this paraphrase to:

“Successful interventions to promote capabilities at any

age do what successful parents and mentors do”

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

95 / 122

Mechanisms—producing effects

(a) Information

(b) Changing preferences of parents

(c) Parental response to child’s curiosity and interest induced by

participation in the program

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

96 / 122

Figure 22: Parental Warmth, Perry Preschool

.

.4

Density

.3

.2

.1

0

-2

-1

0

1

Parental Warmth

2

3

Pooled

Control

Treatment

Note: This figure presents the densities –pooled and by treatment status– for a single factor summarizing a set of questions in

the Perry questionnaire attempting to measure how much affection the child gets from the parent(s).

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

97 / 122

Figure 23: Family Conflict, Perry Preschool

.

.8

Density

.6

.4

.2

0

-2

0

2

4

Family Conflict

Pooled

Control

Treatment

Note: this figure presents the densities –pooled and by treatment status– for a single factor summarizing a set of questions in

the Perry questionnaire attempting to measure family conflict in the household.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

98 / 122

Figure 24: Parental Authority, Perry

.

.4

Density

.3

.2

.1

0

-4

-2

0

2

Parental Authority

Pooled

Control

Treatment

Note: this figure presents the densities –pooled and by treatment status– for a single factor summarizing a set of questions in

the Perry questionnaire attempting to measure how much discipline the child is subject to from the parent(s).

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

99 / 122

Figure 25: Spending per student on pre-primary education was low in

Japan in 2009

Note: The bars show public (bottom part) and private (top part) education spending in US

dollars, adjusted for price level differences across countries, for children too young for primary

school. Annual spending is based on the number of students, calculated on a full-time basis.

Source: OECD (2012f), OECD Education at a Glance 2012.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

100 / 122

Understanding the Dynamics of Skill Formation:

Skills Beget Skills

Synergisms: Skills Enhance Each Other

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

102 / 122

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

103 / 122

Figure 26: Framework for Understanding Skill Development

Prenatal

Inherited

Traits

Prenatal Investments

Skills

Birth

Skills

Childhood

Skills

Adulthood

Parenting,

Environment, School

Parenting,

Environment, School

Higher Education

Earnings

Crime

Health

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

104 / 122

Static complementarity: Having higher level of a skill boosts

productivity of other skills in investment and performance

Dynamic complementarity: Investing today boosts the skill base

for tomorrow

Dynamic complementarity increases with age

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

106 / 122

Critical and sensitive periods

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

107 / 122

But Early Life Conditions Are Not the Full Story:

Resilience, Recovery, and Repair

Many Later Remediation Efforts Targeted to the Less Able

are Costly and Often Ineffective

But Some Adolescent Policies are Effective Mentoring and

Information has a Powerful Effect

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

110 / 122

The policies that are effective for adolescents provide

mentoring and integrate schooling and work. At the core of

effective mentoring is what is at the core of effective

parenting: attachment, interaction, and trust. Effective

policies focus on developing social and emotional skills,

teaching conscientiousness.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

111 / 122

Mentoring can be effective—workplace-based intervention

shape noncognitive skills.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

112 / 122

What about promoting education?

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

113 / 122

Early development is as important as education in promoting

wages, employment, and health.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

114 / 122

Disparities by Education (Post-compulsory Education)

• Education, Wages, Employment, and Health

Note: Conti and Heckman (2010). Author’s calculations using British Cohort Study, 1970.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

115 / 122

Schooling promotes cognitive and noncognitive abilities

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

116 / 122

Expected value of te

0

Expected value of test

Expected value of test

Expected value of te

0

0

0

Figure

27: Causal Effect of Schooling−.5 on ASVAB Measures of Cognition

−.5

−.5

Less than 12

12

13 −15

16 or more

Less than 12

12

13 −15

16 or more

Years of completed schooling at test date

Years of completed schooling at test date

0.5

0

−0.5

Expected value of test score, covariates fixed at mean

1

1.5

1

.5

0

−.5

Less than

12 than 12

Less

12

Years ofYears

completed

schooling

at test date

of completed

schooling

at test date

of test score, covariates fixed at mean

(c) (c)

1.5

1.5

1

1

.5

0.5

0

0

−.5

−0.5

13 −15 13 −1516 or more

16 or more

12

f test score, covariates fixed at mean

(b) Math

(b) Knowledge

(b)

1.5

Mean value of test score, covariates fixed at mean

Mean value of test score, covariates fixed at mean

1.5

Expected value of test score, covariates fixed at mean

(a) Paragraph (a)

Comprehension

(a)

−.5

13 −15

16 or more

Less than 12

12

13 −15

16 or more

Less than 12

12

Years of completed schooling at test date

Years of completed schooling at test date

13 −1513 −15 16 or 16

12 12

more

or more

Years of

completed

schooling

at testatdate

Years

of completed

schooling

test date

Less than

Less12

than 12

(d) (d)

1.5

Source: Heckman et al. (2006).

Notes: Mean effect of schooling on components of the ASVAB. The first four

1

1

components are averaged to

create

males with average ability. We standardize

the test scores to have within-sample mean zero and variance one. The model is

estimated using the NLSY79

sample. Solid lines depict average test scores, and

.5

.5

dashed lines, 2.5%–97.5% confidence intervals. Regressors are fixed at means.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

117 / 122

Expected value of test score

.2

Figure 28: Causal Effect of Schooling on Two0 Measures of

Non-Cognitive Skill

−.2

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

−0.2

Less than 12

12

13 or more

Years of completed schooling at test date

Less than 12

12

13 or more

Years of completed schooling at test date

(d) Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale

(a)

Expected value of test score, covariates fixed at mean

Expected value of test score, covariates fixed at mean

(c) Rotter Locus of Control Scale

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

−0.2

Less than 12

12

13 or more

Years of completed schooling at test date

f test score, covariates fixed at mean

Source: Heckman et al. (2006). (a)

Notes: Effect of.8 schooling on socioemotional scales for males with average ability, with 95% confidence bands. The locus of

control scale is based on the four-item abbreviated version of the Rotter Internal-External Locus of Control Scale. This scale

is designed to measure the extent to which individuals believe they have control over their lives through self-motivation or

.6

self-determination (internal control), as opposed to the extent to which individuals believe that the environment controls their

lives (external control). The self-esteem scale is based on the 10-item Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. This scale describes a

degree of approval

.4 or disapproval toward oneself. In both cases, we standardize the test scores to have within-sample mean

zero and variance one, after taking averages over the respective sets of scales. The model is estimated using the NLSY79

sample. Solid lines depict average test scores, and dashed lines, 2.5%–97.5% confidence intervals. Regressors are fixed at

.2

means.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

118 / 122

Summary

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

119 / 122

Returns to a Unit Yen Invested

Rate of Return to Investment in Human Capital

Prenatal programs

0

Programs targetted toward the earliest years

Preschool programs

Schooling

Job Training

Prenatal

0–3

4–5

School

Post-Schooll

• For the disadvantaged, spending in most societies is almost in

reverse order.

• This diagram and its policy message have to be carefully

digested.

• It presents the rate of return to a unit of investment in

parenting at the beginning of the life of the child.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

121 / 122

• Predistribution, not just redistribution.

• Prevention, not just remediation.

Creating Capabilities, September 23, 2014 5:11pm

122 / 122