Guide to Effective Interprofessional Education Experiences in Nursing Education

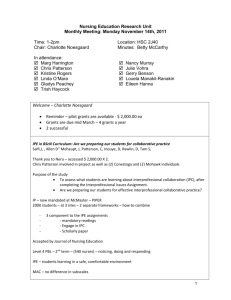

advertisement