on Memory of Age and Experience The Effects Music

advertisement

Copyight

Juwl of Gcrcntology:PSYCHOIDGICALSCIENCES

t998.vol. 538. No. l. P6GP69

194,8by The Cconblogical

Society olAwrica

onMemory

TheEffectsof AgeandExperience

Music

for VisuallyPresented

ElizabethJ. Meinz and Timothy A. Salthouse

Georgia Institute of Technology,Atlant4 GA.

pri'

Increasedage is ofien associatedwith lower levek of perfornance in testsof nenory lor spatial informatbry Th-e

relevant

*ry qurrfrn in the current study waswhether thi- relationship could be moderatedas a function of one's

ardlor knowledge. Stimutusnuterials consistedof short (7-11 note), visual$ presentedmusital melodies,rpiirre

ageand

oid ,tn rn otty equivaleni nonmusical stimulLfanictpanti (N = l2E) wererecruitedfrom a wide range of

no

expericncetevils.iAhougn there werestrong nain efiectsof age and erperience-onmemorytor music,there was

to

moderote

jor

with

individuak

were

smaller

stimuli

these

inlnemory

lor

ililferences

that

the

age-relaed

evlidence

large amou* of experiencewith music-

of age in visual searchof pathology slides.Howeveq signifi1/-\NE importantquestionin the agingliteraturethathasyet

\.-f to resultin a definiteanswerconcemstherelationsamong cantly lower performancewith increasedage has been found

tasks' in the spatial abilities of architects, despite a large correlation

on domain-relevant

andperformance

age,experience,

between age and presumably relevant job experience

in

performance

Althoughageeffectsin the directionof lower

(Salthouse,Babcock, Skovronek,Mitchell, & Palmon, 1990).

older adultshavebeenreportedon manytypesof memory

little evidencefor an

tasks(seeSmith,1996;Craik& Jennings,1992,fotreviews) Salthouseand Mitchell (1990) also found

of spatial ability in

measures

in

interaction

X

Experience

and other cognitivetasks(seeCraik & Salthouse,1992; Age

adults.

unselected

of

a

sample

positive

ef& Hess,1996,for reviews),the

Blanchard-Fields

In ihe domain of music, Krampe and Ericsson (1996)

fectsof experienceon domain-relevanttasksmight be exrecently reported a study in which the effects of age

relations.A findingof

pectedto moderatetheseage-memory

(younger/older) and piano expertisegroup (amateur/expert)

this type would suggestthat normalagedifferencesmay be

were investigated on several musical and nonmusical tasks.

taskswith high

minimizedor eliminatedon domain-relevant

The results oi their study were mixed as to whether expertise

levelsof experiencein thatdomain.

performance. On two

Prior researchinvestigatingrelationsof ageandexperience can attenuateage differences in musical

of age, experinteraction

a

significant

tasks,

motoric

results' speeded

memoryhasyieldedinconsistent

on domain-specific

was found

(musical/nonmusical)

type

group,

task

and

tise

For instance,in a study of memory for chesspositions'

age

with

smaller

associated

was

greater

expertise

suctrthat

skill

and

of

age

Charness( 1981a) found significanteffects

task'

nonmusical

on

the

differencei on the musical but not

(andpresumablyexperience)andan interactionof ageand

However, on performance force variation and musical interper

recalled

chunks

of

number

mean

of

the

a

measure

on

skill

"critical factors that repretation, two measuresclaimed to be

position,but ttreinteractionwasnot significanton thepropordegree" (p. 334)' no intertion of chesspiecesrecalled.Experiencedid not eliminateage ilect musical knowledge to a high

were reported. A

group

expertise

and

age

of

actions

recalling

or

narratives,

differencesin pilots recallingaviation

expectedon these

been

have

might

significant interaction

route,altitude,speed,andfrequencycommands,but therewas

to musical

sensitive

presumably

are

they

because

miasutes

an attenuationof agedifferenceswith experiencefor pilots redomain-relevant

more

have

been

may

thus

and

knowledge

calling air traffic control messageheading commands

than the motoric tasks. Becauseof this inconsistent pattern'

(Monow,Leirer,& Altieri, 1992;Monow, Leirer,Altieri' &

no strong conclusions can be reachedfrom the Krampe and

Fitzsimmons,1994).

Ericssorr(1996)study regardingthe role of expertisein miniStudiesincluding tasksotherthanrecall havealsobeeninmizing age differences in musical performance.

consistentwith respectto whetherrelevantexperiencecanreThJeffects of musical expertiseand agehavealso been studexolder

instance,

For

ducethemagnitudeof agedifferences'

ied on cognitive musical tasks' Halpern, Bartleq and Dowling

periencedtypistsareableto maintaina high levelof overall

( 1995) studied the effects of experience(musician/nonmusiiyping speedalthoughthey areslowerin tappingratesand

age (younger/older), and tonality (tonaVatonal)on the

cian),

choicereactiontimesthanyoungertypistsof thesamenet typreiogniiion of transposedmelodies. In only one of

auditory

maintenance

This

1984;Bosman'1993).

ing speed(Salthouse,

interaction of age

a

ofskill acrossagemaybe a resultofpreservedability to exe- four experiments did they find significant

differences in

age

of

smaller

the

direction

and experiencein

despiteagedifferencesin the

movements

cutetyping-related

no

evidencefor

was

there

and

nonmusicians,

than

musicians

of typing(Bosman,1994).Clancyand

translationcomponent

an old/new

on

with

experience

effects

age

of

the

attenuation

and

Hoyer(1994)alsoreporteda significantinteractionofage

weak evidencein their

was

only

there

Thus,

task.

recognition

effects

negative

the

attenuated

experiencesuchthatexperience

P60

AGEAND EXPERIENCEON MEMORY

P6l

studyfor experience-based

attenuation

of agedifferenceson

background

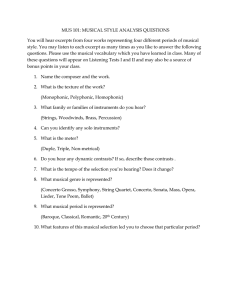

ofconcentriccircles(seeFigurel). In bothcases,

therecognitionof musicalmelodies.

memorywasassessed

by immediatewrittenreproductionof

It is possiblethatfailureto find an ageby experience

inter_ thestimuluspattemsaftereachof four brief (5_seiond)presen_

actionin theHalperneral. (1995)anaotneistudiesis a result tations.

containinga wide varietyof itemsconQuestionnaires

of differinglevelsof domain-relevancy

in the tasks.Morrow

cernedwith fypeandfrequencyof experiencewith musicwere

andhis.colleagues

(Morrowet al., lgd4) havesuggested

that

alsoadministered

to all participants

"expertise(domain

in thepreliminarystudies.

knowledge)cancompensate

hylothesized

majorresultin bothstudieswasa significantlnteraction

-The

agedeclinesin thecognitiveresources

nec"ssaryto perform of experience

andstimulustypesuchthattheeffectsof musi_

pilot taskswhenbothmaterialsandprocedures

aretrigirlyrete_ cal experienceweremuchlargerin thememoryfor musical

vantto p_iloting"

(p.la5). Therefore,althoughthemaierials stimuli thanfor nonmusical

stimuli.Moderatepoiitive correla_

use-d

by Halpernandhercolleagues

(i.e.,aurallypresented tionsbetweentheindexof musicalexperience

andmemoryfor

melodies)werepresumably

domain-relevant,

themusicrans_ musicalstimuli(i.e.,r = .56in preliminaryStudyl, andr =

positionrecognitiontaskmay not havebeenhighly relevantto

.47in PreliminaryStudy2) butnotfor nonmusical

stimuli(i.e..

experiencewith music.

r = in PreliminaryStudy| = .28,andr = .22in preliminary

In particular,their recognitiontask may not havebeen Study2)

werealsofoundin bothstudies.In addition,in thl

highly domain-relevant

because

it did not drawheavilyon

secondpreliminarystudy,a brief testof musicalnotation

knowledgeacquiredthroughexperience.

Onepieceofevi_

performance

knowledgewasadministered.

on thistestwas

dencet}tat supportsthis conclusionis the absenceof an

highly correlatedwith experience

(r - .gO),andadditional

Experiencex{bnalify interactionon recognitionperformance analyses

indicatedthattheeffectsof musicalexperience

on re_

in thatstudy.If musicalexperienceleadsloa greaterknowl_ call were

largelymediatedthroughthis measursofknowledee.

edgeof thetonalstructureof Westernmusic,thenexperienced This finding,

alongwith theinteractions

of experien"."id

musiciansmightbe expectedto outperformlessexperienced stimulus

typeandthestrongcorrelations

betweenexperience

musicianson the tonalmelodies.that is, an Experiencex

andmemoryfor musicalstimuli,suggested

thatthecombina_

StimulusTypeinteractionwouldbe predictedsuchthatexperi_ tion

of thesestimuliandtheimmediate

recall

taskwerehighly

encedparticipantsareableto usetheirknowledgeof muiical

domain-relevant.

Thesematerialsandsimilarprocedures

weri

structureto recognizethoseexcerptsconsistentwith their

thereforeusedin the studyto bereportedin which a moder_

knowledge,

butarelesssuccessful

airecognizingexcelptsthat

atelylargesampleof adultswererecruitedwith a wide ranse

areinconsistent

with theirknowledge.

Thi absence

of thisin_

ofageandmusicalexperience.

teractionin theHalpemet al. (1995)studymakesit difificultto

Althoughmostmemorytasksinvolvea singlerecallattempt

eliminatethepossibilitythatthemusicailyexperienced

were with eachstimulus,threesuccessive

attemptJwere

allowedin

relying solely on their experiencewith aurally presented the

currentstudy.Onereasonfor allowingmultiplerecallat_

music,ratherthanon an acquiredknowledgeof thetonalsfiuctemptswasa desireto obtainsensitivemeasures

of perfor_

tureof Westemmusic.Thus,althoughthJrewereexperience mance,

andwe wereconcernedthattheaveragelevelof per_

effectson this task,thegreateramountsof expenencemay not

formancemight be very low on the first recall attemDt.

havebeenaccompanied

by increased

levelsoidomainknowl_ especiallyin thoseparticipants

with little musicalexperienie.

edgenecessary

to compensate

for thenegativeeffectsof age. The secondreasonfor requiringthree

successive

iecall at_

Alternatively,experienced

participantsmayhavepossessed

the

temptswith the samestimuli wasto investigatepossibleinterrelevantdomainknowledge,but the constrainisof thetask actions

of attemprwith ageor experience.

fni jis potentially

mighthavebeensuchthatit wasnotnecessary

to useit to per_ informativebecause,

for exampli,if olderadultsaresimply

form thetask.

slower-at

encodingtheinformation,thenonemightexpectth!

Oneof themostconvincingwaysto establishthatstimulus agedifferences

in memoryperformanceto deireaseacross

materialsandexperimentaltasksarerelevantto a particulardo_ successive-recall

attemptsbecauseof theadditionalopportuni_

mainis to demonstratea relationbetweenperformanceon the

tiesfor effecriveencoding.Alternatively,the agediiflrences

criticalraskandexperiencein thatdomainwhile demonstrating might increase

acrossattemptsas in i stuayUy Charness

little relationbet'ween

experience

andperformance

on tasksnot

(1981b)in whichthereweregreaterage-relateidi-fferences

in

relevantto thedomain.Two preliminarystudiesweretherefore recallperformance

with increasedstudvtime.

conductedto investigatepossibleexperientialeffectson a task

To summarize,participantsof a wide ageandexperience

involvingmemoryfor visuallypresented

musicalmelodiesand

ftrngewerestudiedto investigatethemoderatingeffeits of ex_

formally similarnonmusicalslimuli (seeMeinz, l996,for a

perienceon therelationsbetweenageandspatialmemoryper_

morecompletedescriptionof thestudies).Themusicalstimuli

formance.Of particularinterestwasa posiibleinteractionof

aredomain-relevant

because

with a few exceptions,

exposure ageandexperience

on therecallof muiical stimuli,suchthat

to printedmusicis involvedin almostall musicalexperiences, experienced

individualswouldshowlittle or no asediffer_

and the task might be considereddomain_relevant

because enceson thesestimuli,whereasin keepingwith repois of ageshort-termmemoryfor visuallypresented

musicis mostlikely

relatedspatialmemorydecline(Cherry& park, 1993;pik,

a componentin musicalsight-reading.

Cherry,Smith& Lafronza.,1990;

Salthouse,

1995),in&viduals

in theseinitial studieswerecollegestudents with little or no experiencewould

. All participants

show

substantial

age_related

because

thegoalwasto examinerelationsof experielnce

to perdifferences.A three-wayinteractionof musicalexperience,

formanceon the experimentaltasks.The musicalstimuii in

age,andstimulustypemight alsobeexpectedif experienceat_

eachstudywerevisuallypresented

7- to I l_notemelodies,

and

tenuatedthe effectsof ageon memoryfor musicalbut not for

thenonmusical

stimuliconsisted

of meaningless

symbolson a

nonmusical

stimuli.

MEINZAND SALTHOUSE

P62

all participants

Becausetime limitationswereanticipated,

andonly

testing,

portion

the

of

stimuli

the

musical

completed

thosefinishingin sufficienttime alsoperformedthe recalltask

on comwith nonmusicalstimuli.Thetaskswereadministered

putersto providegreatercontrolof the testingenvironment

scoringandanalyses.

andto facilitatesubsequent

40.8,SD= 13.0)thanthesubgroupcompletingonly themusicaltask(M = 49.8,Sn= 16.2).In addition,noneof thecorrelationsbetweenageandthevariableswassignificantlydifferentbetweenthesubgrouPs.

Materials

to

by analyzingresponses

wasassessed

Musicalexperience

with

the

frequestions

concerned

containing

a questionnaire

Mmroo

with music.A newlydevised

quincyandtypeof experience

to

wasalsoadministered

knowledge

notation

musical

tlst

of

Panicipants

of

knowledge

to

assess

was

designed

This

test

participants.

all

However,

tested.

participants

were

Onehundredforty-one

of

writtenmusic,with portionsof thetestqueryingknowledge

thedatafrom 13participantswerenot analyzedbecauseof intest

was

in

The

chords.

and

signatures,

pitch,

key

rhythm,

completedataattributableto failure to follow directions,failfrom

were

answers

correct

selected

is,

the

that

form,

matching

ure to completethe session,or computer malfunctions.

andhada maximum

a setof between5 and l0 alternatives,

to be describedarebasedon 128parTherefore,theanalyses

thenamesof

to

identify

were

asked

42.

Participants

of

general

score

through

were

recruited

participants

ticipants.The

identifythe

to

treble

staves;

newspaper

ads,throughspecialrecruitingat schoolsof music musicalnoteson thebassand

to idensymbols;

note

different

by

indicated

beats

numberof

andmusicretailstores,andttrough a local musicians'union.

diminminor,

major,

identify

and

to

key

signatures;

major

tify

rangedin agefrom l8 to 83,andtheir self-reParticipants

comthe

test,

of

The

reliability

chords.

augmented

and

ished,

a

on

activities

in

musical

participating

years

portednumberof

alpha,was.98.Descriptivestatisticson

putedby Cronbach's

primary instntmentrangedfrom 0 to 60. Specialefforts were

itemsandthemusicalnotation

ihe individualquestionnaire

the visualmemorytaskwas

madeto recruitpianistsbecause

2.

Thble

in

listed

test

are

presumedto be similarto bothsight-readingandmemorizaAll musicalstimuliweremelodiesbetween7 andI I notes

tion,bothof whichmaybe especiallyimportantto thedeveldescribedby

andwereadaptedfrom 7-notesequences

long,

participants

listed

percent

of

the

pianist.

Fifty

opmentof a

"tonallystrongitems

were

(1991).

melodies

These

Dowling

pianoastheir primary instrument,with the primary instruconstitutedclearly

mentsof the remainingparticipantslistedas eitherbrass, that startedandendedon thetonic,that

'melodious'in thesense

were

and

that

key,

pattems

in

the

tonal

Background

instruments.

woodwind,string,or percussive

Kershner,

of usingrelativelysmallpitchintervals"(Pechstedt,

characteristicsof the participantsperformingthe musical

7-l

I note

The

l99l).

in

Dowling,

1989,cited

memorytask,andof the53 participantswho alsoperformed & Kinsbourne,

key

within

the

notes

adding

by

were

constructed

melodies

in Thble1.A sethenonmusicalmemorytash aresummarized

work

and

Dowling

the

from

taken

to

the

melodies

perstructure

riesof t-testswereconductedto comparethesubsample

pitches.

No

measure

to

the

values

=

by

assigning

rhythm

(N

adding

with

53)

tasks

nonmusical

and

forming boththe musical

hadfewerthantwo or greaterthansix notes.Melodieswerein

only performingthe musicaltask(N= 75) on

the subsample

the variableslisted in Table 1. There were no significant commontime andweredrawnfrom all possiblemajorkeys.

Rhythmswererandomlyassignedfrom all possiblecombi(p<.01)differencesbetweenthe groupsexcepton age,such

=

(M

of a specifiednumberof notes'Thepossiblenotevalnations

younger

was

tasks

both

that the subgroupcompleting

CompleteSampleandSamplewith NonmusicData

Tablel. ParticipantCharacteristics:

Participants with Nonmusic Data

Entire Sample

SD

n

Age

VoFemale

Education

Healthrating

Vocabulary

Yearsof musicalactivityprimary instrument

Hours/weekmusicalactivitycunently

Hours/weekmusicalactivitymost activetime

Self-ratedmusicalability

Musical notationknowledgetest

128

46.r

66.4

t5;7

Age r

15.6

r.9

t3.4

t2.5

2.9

0.9

5.0

r5.l

4.6

8.7

t4.g

2.7

19.3

-0.16

-0.06

0.l3

0.15

Mean

53

40.8

ffi.4

t6.4

2.0

SD

Age r

13.0

;

t.0

-o.r+

t2.o

r3.6

0.21

0.34

0.14

4.18

6-4

10.7

-o.14

15.8

4.24*

16;l

l9.l

-o.18

1.3

14.5

4.26x

4.2r

2.8

20,7

1.4

14.4

-o.30

4.21

I J.J

5.1

from I = excellent to 5 - poor' The vocabuNole: Education refers to years of formal education, and health rating is a self-assessment on a scale ranging

choice tests. Self-rated musical ability is

multiple

=-20)

and

antonym

synonym

(maximum

".-..

responses

of

correct

number

lary scorc is the sum of the

based on a I (poor) to 5 (excellent) scale.

*P <.ol

AGEAND EXPERIENCEON MEMORY

uesincludeddonedhalf (3 beats),half (2 beats),dottedquarter

(1rlzbeats),quarter(l beat),eighth(r/zbeag,andsixteenth('/l

beat).Noneof themelodieswereassigned

th" ,"-" sequence

of rhythms.Theorderof notevalueswasassignedin iuch a

way that thecombinationof melodyandrhythm seemedtypi_

cal of Westernmusic,asjudged by two individualswith

greaterthanl0 yearsof musicexperience

each.Key andtime

signatures

aswell asclef wereprovidedto theparticipant.

Thenonmusicalbackgroundwasconstructed

to bssimilarin

all of its components

to themusicalstaff.Themusicalstaffcon_

sistsof fivelinesdividedinto two measures,

andthenonmusical backgroundwasfive concentriccirclesdividedinto two

equalhalves.Thesymbolswerealsoconstructed

to be similar

to musicalnotation,butnot recognizable

asmusic.Therewasa

nonmusicalstimuluspairedwith eachmusicalstimulus,such

thata l:l mappingcouldplacesymbolson boththestaffand

circle.Extrasymbolswereincludedon thecircleto parallelttre

key andtime signanues

on themusicalstimuli.Thenonmusical

stimuli were,however,arrangedaccordingto a differentpitch

orderthanthemusic.For example,theD in a musicalstimulus

corresponded

to anE in thenonmusicalstimulus.Thepattem

in which thenonmusicalstimuli werearrangedwascomposed

soasto reducethepossibilityof encodingby anytonalmusic

strategy.

An exampleof a musicalstimulusandthecorrespond_

ing nonmusicalstimulusareshownin Fieurel.

Design and Prccedure

In the single sessionlasting benveen2 and 2.5 hours, partici_

pants completed a consent form, a demographicinformation

sheet,two brief vocabulary measures(rnultiple_choice syn_

onym and antonym testsdescribedin Salthouse,1993),the mu_

sical notation test,and the musical experiencequestionnaire.

They then received supervised practice using the computer in_

terface to reproducethe musical melodies. There were three

practice melodies, with the first provided to the participant on a

piece ofpaper so that he or she could practiceusing ihe inter_

face without relying on memory. Informal comments collected

by participants indicated that threepractice trials were sufficient

to be comfortable in using the interface. Two blocks of six

melodies each followed the practice trials, and an additional

block of six nonmusical stimuli on the circular, nonmusical

background was administered if time permitted. The stimuli in

this last block were formally identicalio those in the fint block

of musical stimuli, but convertedto nonmusical stimuli. The

presentationorder was always practice(music), music, music,

practice (nonmusic),nonmusic.Two setsof melodieswere

used,each with equal numbersof melodies of differing lengths.

Set one was usedin the first music condition and the nonmusi_

cal condition, and settwo in the secondmusic condition.

Participantsviewed the stimulus presentedon a computer

screenfor 5 seconds,and then attemptedto reproducethe ob_

Table2. DescriptiveStatisticson ExperienceMeasures(N = | 2g)

Experience Measure

SD

Range

7o minimum

responses

Component Loading

CI

C2

c3

0.38

0.32

0.39

0.3r

0.s3

0.36

o.29

0.53

4.57

-.0.07

-0.63

-0.07

4.27

o.t2

-o.63

4.20

0.24

0.26

0.r0

o.27

-0.30

o.tz

0.55

4.25

0.r0

0.49

0.14

-0.40

0.20

-o.30

0.28

4.20

0.14

4.24

0.35

-o.30

-0.03

4.27

8.37

0.42

2.99

0.r5

r.60

0.08

Correlation with age

Correlation with corrctly placed musical stimuli (third attempr)

Correlation with correctly placed nonmusiial srimuli (third attempt)

4.12

*0.63

0.04

0.04

0.21

-0.20

Correlations with subjective overall similarity rating

*0.65

0.21

0.00

0.03

*0.75

0.19

0.05

0.02

Years of musical activity-primary instrument

Years of musical activity-secondary instrument

Yearsof private study-primary instrument

Years of private study-secondaryinstrument

Number of paid performances

Number of solo recital performances

Number of accompanying performances

Number of ensembleperformances

Hours/week alone practice-currently

Hours/week alone practice-most active time

Hours/week deliberate alone practice-cunently

HourVweek deliberate alone practice-most active time

HourVweek total musical activity-currently

Hours/week total musical activity-most active time

HourVweek sight reading-currently

HourVweek sight reading-most active time

Hours/week memorization-currently

HourVweek memorization-most active time

Self-rated musical ability

Self-rated sight reading ability

12.5

A 1

4.8

t.2

245.7

12.8

47.7

238.6

2.1

9.3

1.5

l-3

4.6

t4.9

0.8

J-l

0.7

3.0

2.7

2.5

1 5I.

8.8

5.6

2;1

774.2

26.9

163.9

620.1

4.5

9.9

3.9

8.9

8.7

15.9

2.2

4.4

t.o

+.)

t.3

t-J

M0.0

G41.0

u24.0

0-t6.0

0-5000.0

0-150.0

0-1300.0

0-3500.0

0-30.0

o-45.0

0-30.0

042.0

0-45.0

0-70.0

0-20.0

u24.0

0-10.0

0-20.0

1.0-5.0

1.0-5.0

t2.5

44.5

28.|

64.8

tu.8

35.9

6't.2

35.2

64.1

r3.3

68.0

15.6

53.9

I t.7

67.2

27.3

77.3

34.4

22.7

38.3

Eigenvalues

Proportion of variance accounted for

Musical notation knowledge test - Descriptives and

correlations with the components

* p< . o l

19.3

l4.S

M2.O

t2.5

0.66

0.60

0.59

0.48

0.46

0.43

0.48

0.s0

0.73

0.82

0.66

0.78

0.78

0.87

0.61

0.57

0.57

0.67

0.73

030

{r.J/

{J.ll

-o.16

4.44

0.28

0.06

0.r3

0.39

0.61

-O.15

0.01

4.23

0.06

-{.28

0.1I

-O.03

0.00

-0.00

0.17

0.t9

-.X.15

-0.09

0.15 -{.10

0.u

0.03

0.03 {.03

P64

MEINZAND SALTHOUSE

servedpatternon a musical staff or nonmusicalbackground

that appearedon the computer screen.The recall attempts were

produced by pressingarrow keys to position the desired note

on the staff, and then using the arrow keys to identify which

type of note (i.e., quarter,half, eighth) was to be placed in the

chosenposition.An exampleof the computerinterfaceis illustrated in Figure 2. After the participants had placed all of the

"Enter" key was pressedto

notes they could remember,the

view the stimulus again for five seconds.The secondstimulus

presentationwas followed by a secondrecall attemptin which

the previouslyplacednoteswere displayedandcould be added

to, changed,or deleted.A total ofthree presentationsand recall

attemptswere administeredin this mannerfor each stimulus.

Participantswere thoroughly debriefed following the testing.

Scoring

Each symbol placedon the staff was assignedone of four

scoretypes: correct,colrect placement,correct symbol, or incorrect. Correct scores were those that were correct both in

placementas well as in symbol type.A colrect placementscore

was assignedto responsesin which the vertical position on the

musical staff or nonmusical background was colrect, but the

symbol chosenwas incorrect.Those correct symbols with in-

MusicalSymbolson Staff

correct vertical or horizontal positioning were designatedas

conect symbol, and those with incorrect symbol type and

placementwere designatedas incorrect.Although it was possible for participants to correct their incorrect responsesacross

repeatedrecall attempts,no significant decreasesin the number of errors across attempts occurred for any elTor type.

Additionally, the frequencyof errorswas quite low in all cases

(i.e., meansof lessthan l.l ), and thusthe error analyseswill

not be discussedfurther.

Two criteria were usedto scorethe reproductionresponses.

The conservativecriterion began scoring eachresponsesymbol at the beginning of the melody, matching sequentially,so

that, for example, the third symbol in the responsemelody was

scoredagainstthe third symbol in the stimulus.This criterion

is conservativebecauseit does not accountfor possibleinsertions or omissions.

The liberal criterion also beganscoringeachresponsesymbol at the beginning of the melody, however, when it reacheda

symbol that was incorrect (i.e., not matching on symbol or

placement), a serial searchwas performed uritil an item matching on either symbol type or vertical position was found. Once

a match was found, the searchcontinuedwith the next symbol

from the stimulus note that was last matched.If no match was

MusicalStimuliInterface

ftosr <ENTEF> t'h.n dq|e erturiE not$.

Prg€s O lo r€mve a notg.

E:IJ J . ) f) b

flr r r P ?

.-

-'

o

a

Circles

Symbolson Concentric

Nonmusical

Arrow keys rno\D ct sor. Place w/ lspee] .

StimuliInterface

Nonmusical

Press <ENTEF> r,han cbm €nio|ilg swnbols

PrgesD io fdr|o\re a sYrbd

. @ .

\

6, /

B .

\ \ \

d

/

/

f

Arow ksys pcition box. Place w/ lsPacel.

Figure i. Example of a musical stimulus and the corresponding nonmusical stimulus.

Figure 2. Illustration of musical and nonmusical stimuli computer

interface.

AGEAND EXPERIENCEON MEMORY

found,ttresymbolwasscoredasincorrect,andthe scoringre_

sumedat thenextsymbol.This scoringcriterionis moretib_

eral thanthe conservativecriterion becauseit takesinsertions

andomissionsinto accounton thescoring.However,thecorrelationbetweenthesetwo criteriawasvery high (r = .99),and

consequently

all subsequent

analyseswereperformedusing

theconservative

criterion.

A subjectivescoringmethodwasalsousedwith themusical

stimuli to evaluatepossiblequalitativedimensionsof recall

performance.

Thefinalresponse

attemptfor eachof the 1536

(i.e.,128X 12)response

parternswasindependently

ratedon

four criteriaby a musicianwith over 15yearsof musicalexpe_

rience:tonalify, rhythm,contour,andoverall similari$ to ihe

stimulusmglody.Theratingsrangedfrom I lcompletetydis_

similar)to 5 (identical).Inter-raterreliability,assessed

by com_

paringtheratingson a subsetof 96 stimuli with a secondinde_

pendentrater,washigh (r = .94,.95,.97, and.96for overall

similarity,rhythra contour,andtonality,respectively).

. As onemight expect,thecorrelationsamongtheratingsfor

theseattributeswerehigh (i.e.,r > .84).Conelationsbetlween

thefour rating scalesandthe computer-derived

scoreswere

alsoquite high. To illustrate,the correlationsbetweennumber

of symbolscorrectlyplaced(conservative

criterion)andrat_

ingsof overallsimilarity,rhythm,contour,andtonalitywere

.97,.93,.88,and.93,respectively.

Because

thesehighc-onelationsimply thatthedifferenttypesof scoresrver"uJry similar,

all subsequent

analyseswerebasedon thecomputer-derived

(conservative)

scor€s.

F9r thefollowing analyses,

correctscoresfrom eachattempt

on themusicalstimuli wereaveragedacrossthe l2 stimulus

pattems,andthe correctscoresfrom eachattempton the non_

musicalstimuliwereaveraged

acrossthe6 stimuluspattems.

Reliability of the musicalrecall, computedby using the

Spearman-Brown

formulato boostthecorrelationbetweenthe

averagecorrectscoreson the final attemptfor thetwo blocks,

wasgreaterthan.99.

Rrsulrs

Musicalexperience

A principalcomponentsanalysiswasperformedon the experiencequestionnaireitemsto transformthem into a few.

moregeneralvariablesthat could parsimoniouslyaccountfor

the variancein the original questionnaireitems.Eachcompo_

nentrepresents

a weightedlinearcompositeof thequestion_

naireitemsandaccountsfor thegreatestpossibleproportionof

thevariancein the itemsthatis distinctfrom thevarianceal_

P65

readyexplainedby theprecedingcomponents.

l,oadingsofthe

questionnaireitemson thefour componentswittr eigenvalues

greaterthan1.0arelistedin Table2.

The first principalcomponent,Cl, waschosenasthepri_

marymeasureof musicalexperience

becauseit wasassociited

with a largeproportionof the total variance(42Vo),andbe_

causeall of thequestionnaire

itemshadfairly high loadingson

this componenr

(> 0.4).Althougheachof theremaining-om_

ponentshadsomeitemswith high loadings,theywerenot eas_

ily interpretableandmayhavebeenindicatorsof professional

musicalexperience

(i.e.,accompanying,

ensembleperfor_

mance,and paid performances).

In addition,eachof these

components

accountedfor considerablysmalleramountsof

variancethanthe first(l5Voor less)andnoneconelatedsienificantly with musicalrecall. Correlationsof the experiJnce

componentswith age,musicalnotationknowledge,andrecall

on thetwo stimulustypesarcreportedin Thble2.

Domain-Relevance

Stimulustypeeffects.- Beforeproceedingto morecomplex analyses,it wasfirst necessary

to confirm thattheperformancemeasurein this taskwasrelevantto musicalexperi_

ence.One way to do this was to determinewhethei the

ExperienceX StimulusTypeinteractionwassignificant.Only

thoseparticipantswho completedthe recall taskwith botlr

stimulustypeswereincludedin thisanalysis.Characteristics

of thissubsample

(N = 53) arecontained

in Thblel, andcorrelationsamongexperience,

musicalknowledge,age,andrecall

for this samplearelisted in Table3. Note that althoughthe

subsample

wassomewhatyoungerthanthetotal sample,the

subsample

still hada wide rangeof ageandwascomparable

wjth thetotal sampleon mostrelevantcharacteristics.

Usingonly thesubsample's

datafor bothmusicalandnon_

musicalstimuli,regression

analyseswereconductedwith stimulus type and experienceas predictorsof recall accuracy.

Recall attemptswerelargely cumulative,and the rangeof

scoreswaslargerwith successive

attempts,andthus,this analysis wasperformedon thefinal recallattemptonly.Therewere

significantmaineffecrsof stimulustype,F(1,51)= 133.72,

(Ms [and.SDs]

= 4.7(2.6),and1.9(1.4)for musicalandnonmusicalstimuli,respectively),

andexperience,

F(1,51)=29.M,

but theseeffectswerequalifiedby an interactionof stimulus

typeandexperience,

F(I,5 I ) = 70.80.As expected,

thisinteractionwasattributableto significanteffectsof experience

on

themusicalstimuli(i.e.,F'(1,51)=64.96,B =.75) butnoton

thenonmusical

stimuli(i.e.,l'(1,51)= .07,g =.M).

Table3. CorrelationsAmongExperience,

MusicalNotationKnowledge,Memoryperformance,

andAge

r

l. Age

2. Experienceu

3. Musicalnotationknowledgetest

4. Musicalmemory

5. Nonmusicalmemory

-0.1I

4.21

-o.31

-o.35

2

3

4.r2

4.17

0.75*

0.85*

0.75*

0.04

0.87*

0.l8

4

4.43*

0.63*

*

0.81

o.34

Note" Above the diagonal are correlations for all subjects (N = 128). B,elow the diagonal

are correlations for only those with nonmusical aata 1lv = 53f

'Experience refers to the first principal

component from the analysis of the experiericequestionnaire.

*P < .ol.

A,IEINZANDSALTHOUSE

P66

Musicallmowledge.- Anotherindicationthatperformance

is sensitivityto domainknowlmeasrues

aredomain-relevant

that the absenceof an

was

earlier

Indeed,

it

argued

edge.

Experiencex Tonaliryinteractionin theHalpemet al. (1995)

reto weakexperience-knowledge

studycouldbeattributable

lations.Thus,it is our argumentthatexperiencealoneis not

relations;

sufficientto producestrongexperience-performance

possess

levelsof

must

higher

individuals

experienced

rather,

relevantknowledge,presumablyacquiredthroughrelevantexperience,andtheperformancemeasuremustbe sensitiveto

domain-relevant.

thisknowledgeto be considered

Therefore,anotheranalysiswasperformedpredictingrecall

performanceon the final attempt,this time with knowledge

(i.e.,scoreon themusicalnotationtest)andstimulustypeas

predictors.Therewasa significantmaineffectof knowledge,

f(1,51)= 70.73,butnotof stimulustype,F(1,51)= .13.Most

importantly,theinteractionof stimulustypeandknowledge

to sigF(1,51)=99.63,whichwasattributable

wassignificant,

nificantmaineffectsof knowledgeon themusicalstimuli,

stimuli,

f(1,51) = 162.68,9= .87,butnoton thenonmusical

f(1,51)-- l;79,P = .18.

Thesetwo setsof resultsclearlyindicatethatthemeasures

of musicalmemoryin thecurrentstudyarcsensitiveto experiencewith musicandto knowledgeaboutmusicalnotationthat

analyses,

Subsequent

acquiredwith experience.

is presumably

experience

age

and

of

the

interrelations

focused

on

therefore,

on thesemeasures.

periencereflecteda tendencyfor therelationsbetweenexperienceandmemoryperformanceto be strongerwith greater

Althoughthenonlinearpatternwas

amountsof experience.

with the

significant,the proportionof varianceassociated

with the

quadratictrendwassmallrelativeto thatassociated

nonlinthe

(i.e.,

vs

and

consequently

.04

.40),

Rz=

lineartrend

analyses.

earrelationswereignoredin subsequent

Age x Experiencex Anempt.-Table 4 containsthemean

numberof symbolscolrectlyrecalledasa functionof experiencelevel,agedecade,andattemptnumber.A repeatedmeaon thesedatawith

analysiswasconducted

suresregression

andattemptnumberaspredictorsof musical

age,experience,

attemptswerelargelycumulative

recall.Scoreson successive

from Attempt I wereinthe

symbols

for example,

because,

2 unlesssymbolswere

Attempt

from

in

the

score

cluded

deletedby the participant.The main effects of attempt,

F(2,248)= 164.48,age,F(|,124) = 29.33,andexperience,

of attempt

F(l,124) = 30.59,werequalifiedby interactions

=

F(2,248)=

and

experience,

attempt

35.26,

andage,F(2,248)

andage,F(|,124) =7.65.Thethree12.20,andexperience

andattemptwasnot signifway interactionof age,experience,

icant,F(2,248)= 2.50,P = .09.

Examinationof themeansinvolvedin theserelationsrevealedthatparticipantsplacedsignificantlymorecorrectnotes

trial (Ms andSDs= I .4(l.l ), 2.9(2'l), and

on eachsuccessive

respectively),

4.0(2.5)for thefirst,second,andthird attempts,

wasgreaterfor exandthatthis increasein correctplacements

participants

andlesserfor older

perienced

thaninexperienced

AgeandExpeienceEfects

Thediscoverythatthebenefits

thanfor youngerparticipants.

weregreaterfor experiencedand

of repeatedpresentations

wereconductedto

Nonlinearrelations.- Initial analyses

youngindividualssuggeststhat the poorerperformanceof

determinethe magnitudeof anynonlineareffectsof ageand

experienceon the musicalrecall measure(final attempt). older and inexperiencedindividualswas not simply atHierarchicalregressionanalyseswereusedfor this purpose tributableto a sloweror lesseffectiveinitial encodingof the

stimuli,becausetherewasno tendencyfor thedeficitsto be reterminroduced

with thequadraticageor quadraticexperience

Becauseanalysesremediatedwith repeatedpresentations.

afterfint controllingfor thelineareffectsof that variable.The

patterns

each

attempt,andbecause

of

results

on

resultsdid not reveala significantquadraticeffectof age, vealedsimilar

analysubsequent

all

were

cumulative,

largely

=

attempts

=

recall

linear

F(|,I25) .26,I .24, aftercontrolfor thesignificant

performance

the

final

anempt

from

performed

using

were

quadratic

ses

effect

was

a

significant

there

age;

however,

effectof

asthemeasureof recall.

F( 1,I 25)= 14.99,I = -.37, aftercontrolof the

of experience,

The significantinteractionof experienceandagewasnot in

linearexperienceeffect.The significantquadraticeffectof exby Age Decade,ExperienceLevel,andAttemptNumber

Thble4. MeanNumberof MusicalSymbolsConectlyPlacedPresented

Age Decade

30

M S D

4A

M S D

2.6

4.0

0.4

0.9

1.8

l0

0.9 0.4

1.9 0.9

2.9 1.1

t6

0.8 o.4

1 . 7 0.8

2.6 1.0

l4

2.5

5.1

7.0

l.l

2.1

2.0

13

1.9 1.2

4.0 2.4

5.6 2;7

15

2.3

4.4

6.0

20

M S D

Inexperienced

N

Attempt I

Anempt 2

Attempt 3

Experiencedu

N

Attemptl

Attempt 2

Attempt 3

9

l.J

l.l

2.O

2.2

50

M S D

l6

0.8 0.5

1.6 1 . 0

2.4 1 . 6

8

2.5

4.6

5.9

60

M S D

ll

0.6 0.4

1.0 0;7

r . 3 0.9

70

M S D

5

0.8 0.9

1.5 1.8

2.3 2.8

l0

1.5

2.3

2.1

t-z

0.8

l-J

3-t

l.)

r.3 0.9

1.6 0.8

2.t 1.3

Note: Ttrc mean number of symbols acrossthe l2 melodies was 8.83, and thus, this is the maximum possible in each cell.

.Experience level was obtainld by dichotomizing experience by the median score on the first principal cornponent from the experiencequestionnaire.

AGEAND EXPERIENCEON MEMORY

the predicted direction becauseexperiencedmusicians did not

show smaller age differenceson recall of the musical stimuli

than inexperienced participants. Instead, the opposite appears

to be tnre, in that there were smaller age differenies among inexperiencedthan among experiencedmusicians, most likelv

becauseoffloor effects in the older, inexperiencedparticipana.

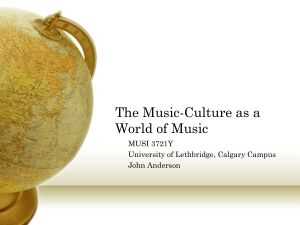

Figure 3 illustrates this trend with data from the final attempt,

with experiencedichotomized by dividing the sample into high

and low groups at the median of the composite index of expi_

rience. The low experience group in this illustration corre_

spondsto a mean of 2.6(SD = 2.8) years of musical activity on

a primary instrument, a mean of 0.3(SD = 0.9) hours per week

of current musical activity, and a mean of 0. I (SD = b.6) current hours per week of practice alone. The high experience

group correspondsto meansof 22.3(SD = 15.9), 9.0(SD =

10.6),and 4.I(SD = 5.6) on theseactivities,respectively.

Additional Arwlyses Conductedfor Interpretation of the Age X

Expeience Interaction

Other mcasuresof expeience. -Although the results sum_

marized in Table 2 indicate that most of the experienceques_

tionnaire items had moderateto high loadings on ttre Rrst prin_

cipal component, separateanalyseswere conducted usingiach

F

(L

llJ

F

F

o

!!8

:c

F

z

o

o

-+-high

:il';'.'.

'

'"'t

TU

O

o

t'

",'

'

J

F

c

.-

-

n

"

t

o-I

o

o.o_oo

E ,

o

(n

D

o o o

oa

5

6

(L

o

trJ

(r

-0.23

- €-'lollr @erience

y*4.90.05*ege

R'=0.18

B"

{o

J

o

(I)

o _ oi

t r t ' o }- q- \

a

"

U

LEr LLI N-- U

%-nq \ " _

a 2

t].

o

o

-a?H

\!

aoX

L

aozntr

t r t r -n - O

\ -\

t

uJ

o

e

e l l

z o

m

4

o

6

0

8

0

AGE (YEARS)

(dichotomized

by medianscoreon the

- Figure3. TheAge X Experience

first principalcomponentfrom an experience

questionnaire)

interactionfor

musicalstimuli. Maximum meannumberof symbolscorrectlyplaced=

8.83.The meanagewx 47.9 (SD = 14.1;for the low experiencioanicipantsand 44.2(SD = 16.8)for the high experience

panicipants,with

rangesof 22-79and I 8-33 years,respectively.

P67

individual item as the experiencemeasure.Individual experi_

enceitem conelationswith musicalmemon'varied from.l6

to .60, but with none of the experiencemq$ures was the interaction of age and experience significant in the direction of

smaller age diftbrencesin the more experiencedparticipans.

Modcration versusmediation. -Theprimarv

focus in this

study was on the moderating effects of experienceon the rela_

tions betrveenage and memory but small negativecorrelations

between age and some experience measures(seeTables I and

2) raise the possibility that lower levels of experiencein the

older sample might have actually mediated some of the nqga_

tive age relations. If this were the case, the age differenies

should be substantially attenuatedafter statistical control of

musical experience.Although the effects of age on musical recall were reducedafter conEolling for experience,i.e.,.P= .19

for age alone and . 14 after control of the first experiencecomponent,the residualeffect ofage was still significantly greater

than.zero. Repeating the regression analyseswith a sample

consistingofonly the upper halfofthe experiencedistribution

also revealedno evidencefor moderation of age effects with

experience,F(1,60) = 3.15,p > .07, or for a r.ill", "ge .oo.lation with musical recall (r = -.48). Thus, the age differences

observed in musical recall were most likely not attributable to

lower levels of experiencein the older participants.

Recencyof expeience. - Becauseof the rather high correlation betweenage and years since musical activity ceased

(i.e., r = .44), it was possiblethat the lack of the predictedage

by experienceinteraction was due to variationsin re."ncy of

experience.Indeed, Ericsson and Charness(1994), in discussingthe existenceof age-relateddecline acrossexperience

levels, have suggestedthat "much of the age-relateddecline in

performance may reflect the reduction or termination of pracnce" (p.744). Moreover, Krarnpe and Ericsson (lg6) reported

that an important predictor of altemate hand tapping speedin

pianists was the amount of deliberate practice in whiih a pianist was engagedduring the past l0 years.Thus, maintenance

of domain-relevantskills may dependon the degreeto which

relevant deliberatepractice is continued in later years.

Given this interpretation, one might expect a significant

three-way interaction of age, experience, and recency of experience in the direction oflarger experience-basedmoderation

of the age relations for individuals with greater amounts of recent experience.However, regressionanalysesrevealedthat

the interaction of age, experience,and recency of experience

(the number of years since musical activity ceased)was not

significant,F = 1.78,p = .19, and furthermore,therewas still a

negative correlation between age and correct recall (i.e., r =

-.53) when the sample was limited to only recently active participants (i.e., those with musical activity within the past 3

years,N = 61,M*= 45.9(15.1). Therefore,the resultsof these

analysesdo not provide support for a moderation of experience effects by recency ofexperience. Additionally, it doesnot

appearthat older adults change their patternsof musical engag€mentsuch that they spend most of their time playing familiar pieces rather than sight-reading, becausewhen the sample was restricted to include only those participants who

reportedthat they currently spent time sight-readingin an av-

P68

MEINZAND SAI:THOUSE

erageweek,thecorrelationbetweenageandcorrectmusicrenegative(i.e.,r= -.54).

call wasstill significantly

Instrumentanalyses.-Although specialeffortsweremade

to recruit pianistsfor this study,thoselisting pianoasa priinstrumentcomprisedonly 67Voof thesammaryor secondary

ple; therefore,theresultsmight havebeenmoderatedby instnrmenteffects.If instrumenteffectsmoderatedthe effectsof

experienceon recall,thenan interactionof experienceandinstrumentmight be expectedwhenpredictingmusicalrecall

experience,

and

from primaryinstrument(piano/nonpiano),

age.In addition,if instrumenteffectsmoderatedthe effectsof

ageon recall,thenan interactionof ageandexperiencemight

be expected.However,therewasno evidenceto suggestthat

therewasan effectof instrumenton correctrecallof musical

effectsweremoderstimuli, F(I,120) = .06,that experience

F(1,120)= 1.39,or thatageeffects

atedby typeof instrument,

F(1,120)= .06.The

weremoderated

by typeof instrument,

three-wayinteractionof age,experience,andinstrumenttype

wasalsononsignificant,

F(1,120)=2.47.

possibility,similaranalyseswereperformedusingonly those

participants

who scoredabove19on the notationknowledge

test.Evenwhenusingthismoreselectsample(N= 59),however,the samepattemof resultsemergedin that therewasno

significanteffectof musicalexperienceon musicalrecallafter

controllingfor knowledge,F( 1,56)= . I 3. Furthermore,the

patternof ageeffectson musicalrecallin this samplewassimilar to thatof theentiresample,wittr a significantnegativecorrelationbetweenageandmusicalrecall(r = -.60).

DrscussloN

Themajorresultof this projectwasthe failure to find an attenuationof thenegativeeffectsof ageon memoryfor domainAlthoughthererelevantstimuli with increasedexperience.

asto whether

inconsistent

been

have

ofprevious

studies

sults

experiencecan reduceagedifferenceson domain-relevant

tasks,attenuationwaspredictedbecausethe currenttaskwas

on thebasisof thesigbelievedto be highly domain-relevant

nificantrelationsbetweenexperienceandrecall performance

in thepreliminarystudiesandin theprimarystudy.Additional

evidencefor therelevanceof thestimuli wasin theform of a

Response

bias.- Becausetherewasa significantcorrela- significantKnowledgeX StimulusTypeinteractionon recall,

which is importantgiventhe argumentthat experienceeffects

tion betweenageandthe averagenumberof symbolsplacedin

-.34),

=

(r

alonemaynot be a sufficientconditionfor establishingtherelthere

might

of accuracy

the final attemptregardless

evanceof a taskto a domain.

response

biasin ttratrelativeto young

havebeenan age-related

Despitesffongeffectsof experienceandof knowledgeon

adults,olderadultscouldhavebeenlessinclinedto guess

recall of the musicalstimuli, andstrongage-relatedeffectson

whenthetotalnumberof symwhenuncertain.Nonetheless,

memoryfor bothmusicalandnonmusicalstimuli,therewas

bolsplaced(correctandincorrect)wasusedasa covariatein

pattern

no evidencein this studythat greateramountsof experience

X

of

results

in

this

the

Age

Experience

analysis,

the

moderatedtheeffectsof ageon performancein a domain-releAlso, it

analysiswasidenticalto thatof theinitial analysis.

for this findingwere

vanttask.Severalpossibleexplanations

moreon

doesnot appearthat certainindividualsconcentrated

of thepredictedAge X Experience

explored,but theabsence

pitch values(verticalposition)thanrhythms(notetype),bewith correctpitchvalueswereused interactioncouldnot be accountedfor by recencyof expericausewhenall responses

biases,or

activity,response

ence,reductionsin sight-reading

asthe dependentmeasure,the pattemof resultswassimilar to

with theexceptionof a nonsignifi- instrumenteffects.Moreover,althoughthe brief exposurepethatof theinitial analyses

for the older

riod (5 seconds)might havebeena disadvantage

(i.e.,F(\,124)= l.9l).

cantinteraction

of ageandexperience

adults,thepresenceof anAge X Attemptinteraction,in which

agedifferenceswereactuallylargerwith moreattempts,indiRelatioruBetweenExperienceandKnowledge

catesthat older adultswerenot ableto capitalizeon the reTo furtherexplorethe relationshipbetweendomainexperipeatedexposuresto the stimuli. Finally, thepossibilitythat

enceandknowledge,andto investigatethepossibilitythat the

effectsof experienceon taskswithin a domainaremediated someof the negativeeffectsof agemight havebeenmediated

wasexplored,but there

amountsof experience

throughknowledgeaboutthai domain,theeffectsof experi- by decreased

encewereexaminedbeforeandaftercontrolof themusical waslittle attenuationof age-relatedeffectsafter conhol of the

notationknowledgemeasure.Hierarchicalregressionanalyses availablemeasureof experience.

A discoveryof a significantAge X Experienceinteraction

with experienceandscoreon thenotationtestaspredictorsof

on

musicalrecall wouldhavebeenconsistentwith the view

were

no

signifirevealed

that

there

additional

musicalrecall

thatolderadultswereableto maintainhigh levelsof perforcanteffectsof experienceon recall performanceafterperforspatialmemorytaskdespitelower

mancein a domain-relevant

manceon themusicalnotationtestwasheldconstant.TheF

142.95and.40, levelsof perfonnanceon generalspatialmemorytasksbewith experiencewere

andR2valuesassociated

causeof the positiveeffectsof experience.In otherwords,berespectively,whenexperiencewastheonly predictor,but only

causepeopleoftencontinueto engagein musicalactivitieslate

.74 md.00 aftercontrolof theknowledgevariable.This patthattheeffectsof musicalexperience into life, theymighthavebeenexpectedto somehowcircumternof resultssuggests

on this taskwerealmostentirelymediatedthroughthemea- ventdecliningabilitiesto maintainhigh levelsof performance

in tasksrelevantto their experience.However,despitethe use

sureof musicalnotationknowledge.

is

of a taskin which moderatelylargeexperienceeffectshave

recall

task

musical

argued

current

It could be

that the

experiencewith music(up

evenconsiderable

beenestablished,

qualitativelydifferentfor thosewho haveno musicalbackfor the age-relateddifgroundbecausefor thoseindividualsthestimuli wouldconsist to 60 years)wasunableto compensate

on this particulartask.

of unfamiliarstimuli,whereas ferencesin memoryperformance

configurations

of meaningless

Onefactorthat may havecontributedto the observedage

individualswith a backgroundin musicwouldbe ableto code

differencesin this studywasthatthecomputerinterfacecould

the musicalsymbolsasmeaningfulnotes.To investigatethis

AGEAND EXPERIENCEON MEMORY

have placed a large burden on the working memory of participants.Age-relatedworking memory limiAtions havebeen welldocumented(e.g.,Salttrouse,1994),and thus the useof an unfamiliar computer interface could have contributed to the poor

performanceof older adults. Severalefforts were made to minimize the influence of this factor. First, the interface was relatively simple and included the use of only six different keys

with no time pressure.Second,extensiveguided practice was

given, usually lasting around 15 minutes, and feedbackfrom

the participants indicated that they were comforrable with the

interfaceby the end ofthe third practicetrial. Nonetheless,although the samepattern of experiential relations was found in

preliminary studies with undergraduate participants using

paper-and-pencilversionsof this task, we cannot rule out the

possibility that older adults were differentially penalized by ttre

computerized nature of this task. That is, older adults might

have found the conversionof ttre stored stimulus information to

a novel interface difhcult becauseof working memory limitations. Also, becauseof this slower conversion,older adults

might have had a longer interval between the presentationof

the stimulus and the time taken to recall the stimuli. which

would necessitateholding the presented stimuli in working

memory for a longer period of time. One meansby which this

interpretation might be investigatedwould involve repeating

ttre study with a different type of responsemode, such as recognition or actualreproduction of the melody on an instrument.

The results of this study are also relevant to the issue of how

experienceexerts its effects on cognitive performance.That is,

an interpretation suggestedby the current results is that the effects of experienceon a task might be explained by the specific knowledge and skills gained ttrough experience.The discovery that most of the effects of experience on the present

task were mediatedthrough the measureof musical notation

knowledge is clearly consistent with this view. However, we

suspectthat other types of knowledge or skills would be

neededto account for the effects of experience on more complex musical activities. For example, the recall of longer, more

complex melodies might draw on more detailed knowledge of

musical notation or of relations among musical notes.

In conclusion, this project capitalized on the breadth of musical experience,musical knowledge, and age in the general

population in illustrating the skilled memory effect in music,

documenting relations among experience,knowledge, and domain-relevant memory and in examining the effects of experience on the relations between age and domain-relevant recall

performance. Becauseno attenuation of the age differences

with increasedamounts of experience was found in this study,

the challenge remains to characterize tasks in which there are

little or no age-relateddifferences and to identify the processes

that allow older adults to maintain high levels of performance

despitelower levels of functioning in many cognitive abilities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This researchwas supportedby MA Training Grant AG00175 to the first

author and NIA Grant 6826 to the second author. An earlier version of this

manuscript received an award for completed researchat the Master's thesis

level from the Retirement Research Foundation and Division 20 of the

American Psychological Association.

We wish to acknowledge the assistanceof Jerry Bowling and Kristen Lukas

in collecting and scoring data, and the assistanceof George Manning in providing the subjective ratings of the data. We also would like to thank John

P69

Haskinsfor programmingthe study,JayDowlingfor theuseof his stimuli,

andRandyEngleandthreeanonymousreviewersfor helpfulcommentson

earlierversionsof this manuscript.

Conespondence

concerningthis articleshouldbe addressed

to ElizabethJ.

Meinz,Schoolof Psychology,

GeorgiaInstiote of Technology,

Atlanta,GA

30332.E-mail:gt4956b@acme.gatech.edu

RgrengNcrs

Blanchard-Fields,

F., & Hess,T. M. (1996).Perspectives

on cognitivechange

in adulthoodandaging.NY: McGraw-Hill.

Bosman,E. A. ( 193). Age-relateddiferencesin motoricaspectsof transcrip

tion typing skill. PsycftologyandAging,8, 87-102.

Bosman,E. A. (1994).Age andskill differences

in typingrelatedandunrelatedreactiontime tasks.Agingand Cognition 1, 31V322.

Charness,

N. (1981a).Aging and skilled problemsolving.Journal of

ExperbnennlPsychology:General,I 10,2l-38.

N. (l98lb). Visualshort-termmemoryandagingin chessplayers.

Charness,

Journalof Gemnnlogy,j 6, 6 1fu 19.

Cherry,K. E., & Pa*, D. C. (1993).Individualdifferenceandcontextualvariablesinfluencespatialmemoryin youngerandolderadults.Psychology

andAging,8, 517-526.

Clancy,S. M., & Hoyer,W. J. (1994).Age and skill in visualsearch.

DevelopmenalPsyclnbgy, 30,545-552.

Craik,F.I. M., & Jennings,

J. M. (1992).Humanmemory.In F.I. M. Craik&

(Fds.),fhcfundbookof agingandcognition(pp.5l-l l0).

T.A. Salthouse

Hillsdale,NJ: Erlbaum.

Craik,F.I. M., & Salthouse,

T. A. (1992).Thehandbookofagingand cogninon.Hillsdale,NJ: F.rlbaum.

Dowling,W. J. (l99l). Tonalstrengthandmelodyrecognitionafterlongand

shortdelays.PerceptionandPsycltophysics,

50,3M-313.

Ericsson,K. A., & Chamess,N. (1994).Expertperformance:Its structureand

acquisition.Arzerican Psychologkt,49,725-747.

Halpem,A. R., Bartlen,J. C.,& Dowling,W. J. ( 1995).Agingandexperience

in therecognitionof musicaltranspositions.

Psychology

andAging, 10,

325:342.

Krampe,R. Th., & K. A. Ericsson.(1996).Maintainingexcellence:

Deliberate

practiceandelite performancein youngandolder pianists.Journalof

Eryerinenal Psychology:General I 25,331-359.

Meinz, E. l. (196). Musical experience,musicallotowledge,and ageefects

on mcmoryfor mzsic.Unpublishedmaster'sthesis,GeorgiaInstituteof

Technology,

Atlanta.

Morroq D. G., leirer, V. O., & Altieri, P.A. ( 192). Aging, expertise,andnarrativeprocessing

. PsycltologyandAging, 7,37G388.

Morrow,D., I*irer, V., Altieri, P.,& Fitzsimmons,C. (1994).Whenexpeftise

reducesage differencesin performance.Psychologyand Aging, 9,

134-148.

Park,D. C., Cherry,K. E., Smith,A. D., & L,afronzaV. N. (1990).Effectsof

distinctivecontexton memoryfonobjectsandtheir locationsin youngand

elderlyadults.Psycb logyandAging,5, 250-255.

Pechstedt,

P.H., KershneqJ.,& Kinsboume,

M. (1989).Musicaltrainingimprovesprocessingof tonality in the left hemispherc.Music Perception,6,

27t298.

Salthouse,T. A. (1984). Effects of age and skill on typing. Journal of

Eryerimennl Psycholog!: General,I 3, 345-37I.

Salthouse,

T. A. (1993).Speedandknowledgeasdeterminants

ofadult age

differencesin verbal tasks.Journal of Gerontology:Psychological

Sciences.48.Y29-V36.

Salthouse,

T. A. (1994).Theagingof workingmemory.Neuropsychology,

8,

535-543.

Salthouse,

T. A. (195). Dtrerential age-rclated

influenceson memoryfor verbal-symbolicinformationand visual-spatialinformation.Journal of

Gercntology

: Psycholagical

Science,508, l9r20l.

Salthouse,

T.A., Baboch R. L., Skovronek,E , Mitchell,D. R. D., & Palmon,

R. (1990). Age and experienceeffects in spatial visualization.

Developmcnnl Psychology,

26, 12U136.

Salthouse,T. A., & Mitchell, D. R. (1990)Effectsof ageandnaturallyoccurring experienceon spatialvisualizationpcrformance.Developmental

Psychology,26,8r''fr54.

Smith,A. D. (1996).Memory.In J. E. Birrcn, & K. W. Schaie(Eds.),

Handbookof the Psychologyof Aging (4th ed.,pp.23G250). SanDego,

CA:AcademicPress.

ReceivedDecember2, I 996

AcceptedMay15,197