Time as a Factor in the Development and Decline of Mental Processes

advertisement

Time as a Fa

Time asa Factorin the Development

andDeclineof Mental

Processes

Timothy A. Salthouse

The theme of this chapteris that it is meaningful

to think of time as increasing and then decreasing as a function ofage. Ofcourse I am not referring to time in an objective physical sense,

but rather functional time in the senseof the

amount neededrequired to carry out many cognitive operations.Severalyears ago Robert Kail

and I (Kail & Salthouse,1994) suggestedthat

time can be viewed as a processingresourcethat

alters with age if changes occur in the time

neededto executeoperationssince fewer operations will be able to be completedin a given period of time. In this chapterI will elaborateon

this perspective,and will summarizesome relevant empirical researchconcentratedon the

adult portion of the lifespan.

I will begin by documenting the lifespan

growth and decline of this resource-based

conceptualizationof time. For this purposeI will

use several measuresfrom tasks that are so

simple that accuracy is nearly perfect, and consequentlyvirtually all of the variation across

people can be assumedto be in terms of how

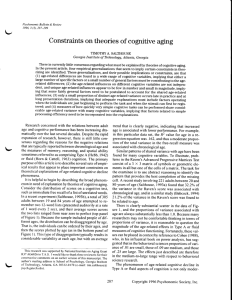

quickly the items can be performed. The first

figure portrays results of measuresfrom two

perceptual speed tasks from the WoodcockJohnsonTestof CognitiveAbilities (Woodcock

& Johnson,1989, 1990)expressedin standardized units. Notice that there is a rapid increasein

the period ofchildhood, followed by a gradual

decreaseacrossthe adult years.This phenomenon is evident with a variety of different tasks,

and strongly suggeststhat there are substantial

age-relateddifferencesin measuresthat might

be hypothesizedto reflect the time required to

executeelementarycognitive operations.

An immediate obvious question is why are

measures of time important? Many other

lifespan changespresumably have no consequencesfor cognition, such as running speed"

bicep diameter,lung capacity,and the color of

one'shair, and thus it is reasonableto ask what is

specialabout measuresreflecting speedofprocessing.

500

uro

E

o

o

(r) 500

I

;

-E

480

I 460

o

1140.

420

400

6

101s20253035404550556065702S80gS

Chronological

Age

Figure I: Mean performance between 5 and 95

years of age on two perceptual speedtests from the

standardizationsample in the Woodcock-Johnson

Psycho-EducationalBattery.

I have two responsesto this question. First, I

will argue that time is unique becauseplausible

theoretical mechanismshave been proposed by

which slower processingcan affect cognitive

functioning. And second"I will describeempirical evidence indicating that measuresof processingtime are actually involved in the age-related differences in many measuresof cognitive

functioning.The empirical evidencewill be described first because discussions of hypothesizedmechanismsare more meaningful when

the to-be-explainedrelations have been establishedto exist.

The primary empirical question of interest is

whether there is evidence for an influence of

time or speedon the relationsbetweenage and

various measuresof cognitive functioning.The

simple answerto this questionis yes, but in order to understand the reasonsfor this answer it

is important to briefly describe the types of

analyticalmethodsthat haveled to this conclusion.

Consider the general case

diator, X. In the present cont

to an index ofspeed ofproct

be virtually any variable h11

tribute to at least some of the

encesin cognition. How can r

age-relatedchangesin X mi1

for age-relatedchangesin y?

lationscould be investigare

tween age and X, betweena

rweenX andY.

But how can one determi

*'hat extent,the relationsim

contributeto the observedrcll

andY? The mere existence<

not sufficient becausea great I

relatedto age,but it is unlike

rnvolvedin the relationsberc

ablesreflecting cognitive fui

.rmple,both gray hair and po<

renrelatedto increasedage in

rn age-heterogeneoussamp

rbundto be related to eachoth

roth are associated

with incre

.''necould not concludethat g

rhe decline in memory thar o

rncreased

age becauseall of

rronsneedto be consideredsin

rs.evidenceis neededto estab

binationof relationsbetweenI

r*'een X and Y do in fact con

.erved relation betweenage ar

Three major techniquesco

restigatethe hypothesizedlinl

I t. All involve examining tbe

rge and Y after eliminatingc

:elationbetweenageand X. In

rectationis that the relation h

'.rill be greatlyreducedor elim

:r is mediatedthroughX.

One possiblestrategyconsis

:rperimental intervention to al

Ideallythe interventionwould o

:ng X in older adultsto the le\t

rnd thereby eliminate the rclar

rnd X. Experimental manipula

mostconvincingway to establi

a causalrelation becauseifX is

rhathas beenalteredthen it mr

tor the observeddifferences.Ur

vention approachesmay not t

presentcontext ifthe X variaH

over a period of many decadc

Time as a Factor in the Development and Decline of Mental Processes

ine of Mental

logical Age

x-c bctween5 and 95

rrual ipced testsfrom the

rhl \\oodcock-Johnson

c'

, to this question'First, I

rn'quebecausePlausible

i h.1\c beenProPosedbY

n! can affect cognitive

d- l ri rll describeemPiris th.rrmeasuresof ProN rnrolvedin the age-renr nr.'u.rr.esof cognitive

'r"-rlcvidencewill be dedr.cttssionsof hYPothr rnrrremeaningfulwhen

l.itr,'nshavebeenestabcal questionofinterest is

encc tbr an influence of

elrtlonsbetweenageand

ocnrtivefunctioning.The

quc.tionis Yes,but in oric'.i:onsfor this answerit

lr ,lescribethe tYPesof

ri h"r'. led to this conclu-

Consider the general case of a potential mediator, X. In the present context X corresponds

to an index ofspeed ofprocessing,but it could

be virtually any variable hypothesized to contribute to at least some of the age-relateddifferencesin cognition. How can one determine that

age-relatedchangesin X might be responsible

for age-relatedchangesinY? Severalsets ofrelations could be investigated,such as those between age and X, betweenage and Y, and between X andY.

But how can one determine whether, and to

what extent, the relations involving X actually

contribute to the observedrelations betweenage

and Y? The mere existenceof each relation is

not sufficient becausea great many variablesare

related to age, but it is unlikely that they are all

involved in the relations between age and variables reflecting cognitive functioning. For example, both gray hair and poor memory are often related to increasedage in adulthood"and in

an age-heterogeneoussample they might be

found to be related to eachother merely because

both are associatedwith increasedage.However

one could not conclude that gray hair mediates

the decline in memory that often accompanies

increasedage becauseall of the relevant relations needto be consideredsimultaneously.That

is, evidenceis neededto establishthat the combination ofrelations betweenage and X and between X and Y do in fact contribute to the observedrelation betweenage andY.

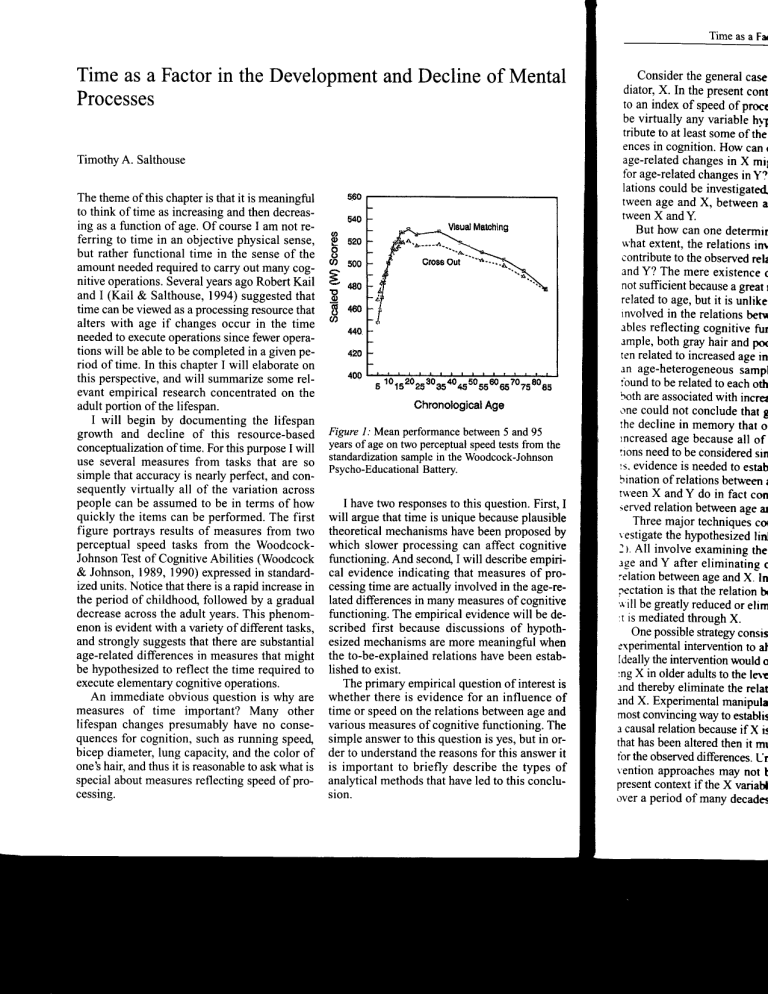

Three major techniquescould be used to investigatethe hypothesizedlinkages (see Figure

2). All involve examining the relation between

age and Y after eliminating or controlling the

relation betweenage and X. In eachcasethe expectation is that the relation between age andY

will be greatlyreducedor eliminatedif much of

it is mediated through X.

One possiblestrategyconsistsof sometype of

experimentalintervention to alter the level of X'

Ideally the intervention would operateby improving X in older adultsto the level of young adults,

and thereby eliminate the relations between age

and X. Experimental manipulation is clearly the

mostconvincingway to establishthe existenceof

a causalrelation becauseifX is the only variable

rhathas been altered then it must be responsible

tbr the observeddifferences.Unfortunately,intervention approachesmay not be feasible in the

presentcontext if the X variable changedslowly

,.rvera period of many decades.Not only might

JJ

Inbffenlbn

l v l

Ac.

-

[Q\-]

l v l

Agc

'[Gl

l Ae.

" l

Agf

Manctrrne

fr*-.1

.'.'-'

I

|

Ae.

HH,nrdu

lo

l

Ae.

Figure2: Schematicillustrationof threetechniques

thatcouldbe usedto eliminatethevariation

betweenageandsomevariableX.

interventionsbe ineffective in reversingchanges

that were slow and gradual,but ifthe changein X

occurred gradually, it may have been accompanied by numerous adaptationsthat might not be

easyto eliminateeven if it were possibleto restorethe level ofX to the earlier state.

A secondpossiblesffategyinvolves the use of

matching by attempting to find people of different ageswho have similar valuesof X. Although

seemingly straightforward this procedurealso

has at least two major limitations. First, when

trying to match on a variable that has moderate

to large relationswith age,as is expectedto be

the casewith X, the matchedsampleswill likely

be small and the range of ages probably restricted relative to the entire sample. Both of

thesefactors will lead to low statisticalpower to

detectrelationsbetweenage andY, and consequently the hypothesisof attenuatedrelations

between age and Y might be supported for artifactual reasons.The second limitation of the

matching procedureis that there is no assurance

that the matching is only on the intendedvariable X becauseseveralvariables may vary concomitantly with X, and one or more of them may

influenceY in addition to, or insteadof, X. To

the extentthat this is the case,one could not be

certain that X was the critical variable responsiblefor the changesinY.

34

Time as a Fa

Timothy A. Salthouse

The third strategythat could be usedto inves- equationmodeling to reducemeasurementerror

tigate the role of a variable X in the relations and minimize biasesin the estimatesof the magbetween age and another variable Y relies on nitude of the relations.However,the analysesare

sometype of statisticalcontrol.That is, statisti- still meaningful with observedor manifest varical control procedures could be used to equate ables,particularly ifreliabilities are availableto

people ofdifferent ageson X by partialing out allow the estimatesof the relations to be adthe linear relation betweenage and X. An advan- justed for measurementerror.

In both commonality analysesand path analytage of equating with statistical procedures

the methods are relevant to time-based interses

rather than through direct matching is that all of

if measuresof processing speed are

pretations

the

analyses,

in

be

used

the availabledata can

measuresof cognitivefunctioning

and

X,

as

used

in

statistical

reduction

is

minimal

there

thus

and

power relative to the entire sample. Statistical are usedasY. Resultsfrom theseprocedureswill

control proceduresalso allow the influence of be illustrated with perceptualcomparison speed

other measuredvariables to be examined and measuresserving asthe X variable,and measures

eliminated by similar partialing techniques.The of performance from three different cognitive

primary assumptionof statistical control proce- tasksserving as theY variable.

As mentioned earlier, perceptual speedmeadures is that the relations between age and X,

quickly eland between X and Y, are mostly linear, or that sures are assumedto reflect how

be percan

operations

cognitive

ementary

yield

linear

the variables can be transformed to

that few

so

simple

are

tasks

is,

the

That

formed.

is

determined,

relation

linear

relations. Once the

virtuit can then be used to adjust the valuesofY to people make mistakes, and consequently

is

adults

normal

across

variation

the

of

remove the influence of X, and allow examina- attyatt

tasks.

perform

the

to

needed

the

time

in

reflected

portion

and

the

tion ofthe relation between age

Administration time for the measurescan be as

ofY that is independentof X.

reliability

Becauseinterventions do not yet appearfea- brief as 60 seconds,but estimatesof

will

be deI

Although

higher.

or

sible, and since matching leadsto substantialre- are often .8

propaper-and-pencil

on

based

results

scribing

procedures

ductions in power, statistical control

patterns

similar

that

noted

be

should

it

cedures,

eliminatfor

method

practical

may be the most

and path

ing the influence of a hypothesizedmediating of results in commonality analyses

time

reaction

with

obtained

been

variable at the current time. Two different statis- analvseshave

not

do

the

conclusions

thus

and

-"usutes,

rpe"d

tical control methodscan be used"both of which

asof

method

particular

to

a

be

specific

to

seem

procearebasedon relatedtypes ofcorrelational

sPeed.

processing

sessing

dures.

Results with three different criterion meaOne method is known as commonality analywill be illushated and in eachcasethe data

sures

sis, and it is useful for determininghow much of

based on samplesof 200 or more adults

were

is

much

how

to

X,

the variance in Y is unique

from l8 to over 80 years ofage. One of

ranging

X

between

is

shared

much

how

and

age,

unique to

on the Raven's

and age. This technique is particularly helpful the criterion variablesis the score

test of

popular

is

a

which

Matrices,

Progressive

when partitioning the age-relatedvariance bein a

9

cells

8

of

in

which

reasoning

inductive

the

age-related

of

causeit can indicatehow much

the reand

patterns

geometric

contain

matrix

(Y)

is

shared

variable

the

criterion

variance in

spondentis requiredto selectthe best comple'

with the hypothesizedmediator variable(X).

A second

Various types of path analysiscan function as tion of the missing cell in the matrix'

of

number

of

the

the

sum

is

variable

criterion

because

the secondstatistical control procedure

in the

trials

five

first

the

across

recalled

items

strengths

relative

the

of

they provide estimates

Test. In this test

of paths from age to X, from X to Y, and from Rey Auditory Verbal Learning

is read aloud

words

l5

unrelated

list

of

the

same

agetoY. The latter path is especiallyinformative

to reattempting

respondent

the

with

times,

five

onY

ofage

becauseit representsthe influence

preseneach

possible

after

as

words

many

as

call

it

can

thus

and

X,

through

that is not mediated

and accuracy

be used to estimatehow much of the age-related tation. A measurereflecting time

Wechsler

the

from

test

Design

variancein Y is not explainedby the mediator on the Block

the third

is

Revised

Scale

Intelligence

Adult

con(X). Ideally the path analysesshould be

test inThis

will

describe.

I

variable

criterion

structural

and

ducted with latent constructs

volves the respondentanen

blocks to match a target panl

These three tests are obv

ent, and they are generalll.

distinctpsychometricfacton

soning,episodic or shon-tern

tial visualization).Eachof th

tablishedto havegood reliab

the teststypicallyexhibit rn

differences.The next figure

from studiesconductedin n

the scoresin eachtest con\.e

viation units from the enrrre:

comparisonsacrossvariablr

range of performance from I

oldestage groups is almostr

tions with each variable.

AgeTrends

Baven's

R€yAVLT

WAISBlod<Delgn

:'igure 3: Mean standardscores(

\latrices (Salthouse,1993),and r

ialthouse,Fristoe& Rhee, 1996

.rrth thesevariablesas criterion r

Time as a Factor in the Development and Decline of Mental Processes

iasurementerror

laresof the mag, th!'analysesare

or nianifest varis are availableto

ationsto be ads and path analYintertrnie-based

e\sing speedare

ritire functioning

e procedureswill

onrparisonspeed

rlc. and measures

flcrent cognitive

ptual speedmeaherrrquickly elns can be pero simplethat few

nscquentlYvirtunormal adults is

pcrtbrm the tasks.

easurescan be as

atcsofreliabilitY

rgh I will be derr-and-pencilPrort :irlilar Patterns

nalvsesand path

r rth reactiontime

'onclusionsdo not

ular methodof asnt criterion meaeachcasethe data

)0 or more adults

ars ofage. One of

c-rreon the Raven's

s a populartest of

r S of 9 cells in a

,rrc'rnsand the ret the best comPle: nratrix.A second

r-rfthe number of

;t tive trials in the

rg Test.In this test

r-ordsis read aloud

nr attemptingto re: alier eachPresentlntc and accuracy

ionr the Wechsler

ier ised is the third

cnbe.This test in-

volves the respondentattempting to assemble

blocks to match atarget Pattern.

These three tests are obviously quite different, and they are generally assumedto reflect

distinct psychometricfactors (i.e., inductive reasoning,episodic or short-term memory and spatial visualization).Eachofthe testshasbeenestablishedto have good reliability, and scoreson

the tests typically exhibit moderately large age

differences.The next figure illustrates results

from studies conducted in my laboratory with

the scoresin eachtest convertedto standarddeviation units from the entire sample to facilitate

comparisonsacrossvariables.Notice that the

range of performance from the youngest to the

oldest age groups is almost two standarddeviations with eachvariable.

AgeTrends

The next figure illustratesresultsu'ith commonality analyses(in the form of a pie chart depicting variance accounted for in the criterion

variable)and path analyses(in the form ofa path

diagram with estimates of the relevant coefficients). Results from both sets ofanalyses are

consistentwith the interpretation that time to

executesimple operationsis an important factor

in the age-relateddifferences in cognitive functioning. This is apparent in the commonality

analysesbecauseestimatesofthe percentagesof

the total age-relatedvariance sharedwith speed

(i.e., the ratio of sharedto the sum of sharedplus

unique-to-agemultiplied by 100)were 98.1 for

the Raven'svariable, 73.2 for the Rey Verbal

Learning variable, and 86.3 for the Block Design variable. The path analysis results are also

CommonalitYEEtimat€€

PathModels

Baven's

o

8

g,

r{l

-l

ReyAVLT

{.t

WAISBlod<Deign

I

INt

" ' ' ! 0 s $ s D F

Raven'sProgressive

Figure 3: Mean standardscores(and standarderrors) as a function of age for the

Block Design Test

Wechsler

and

Test

Learning

Verbal

M"atrices(Salthouse, 1993), and ih. R.y Auditory

path analyses

(Salthouse,Fristoe & nfree, ISSO).Also portrayed are results from commonality analysesand

with these variables as criterion variables.

36

Timothy A. Salthouse

Time as a Facrc

firfrdTrmPrinide)

tary processingoperationstake

formed, then fewer of them can

a given period. This mechanis

very important in timed tesrs

those with low levels of difficu

formance is primarily assesse

number of items completed i

time. However, the limited r

could also affect performancei

situations where a sequenceof

be performed and slow execu

operationsmeansthat later. and

order,operationsare not succes

A relevantmetaphorfor the lim

nism might be an assemblyline

operationsare not completedn

ucts at subsequentstagesmar t

Considerableevidenceindic

creasingage less processine

plished in the same amount (

ample,this phenomenonis er id

lationsof stimuluspresentatio

hoc analysesofthe level ofaccr

specifiedreactiontimes,or u'id

ing reaction time to the amou

processingor to the number ot

must be performed.

The secondmechanismb'r'rr

cessingcould leadto impairme

of cognitive functioning is knon

neity mechanism,and it ma1 og

thereare no externaltime limiu

sumptionin this mechanismis t

successfulmany higher-level ,

tions such as association.inte

stractionrequire that all of the r

tion is simultaneouslyavailab

accessiblewhen needed,then rh

not be completedsuccessfullr.:

the relevantperformanceu'ill b

eral factors probably affect the i

taneouslyavailable informatior

activatethe informationis posru

ticularly important determinan

It could be arguedthat if infc

in the samestateof availabilin

the completionof processingn

layed when the speedof actn

However,if information is lost

displacementthen therewill be

when all relevantinformation i

the duration ofthat period dep<

namicsof the speedof activatl

|

I

E

3

E

Age -+

./

Spood

,.n

2:

fln

\

Gogniton

(Sl'rrulhnc{tyRhtdcl

g

5r

\

l

/N

f,l

r I f f/J"-\onlo

iffi

rlat

./

'

nffir

bldrdl

Figure 4: Schematic illustration of two hypothesizedmechanismsthat might account for the influence of

speedon the relations between age and measuresofcognitive performance.

consistentwith the hypothesizedspeedmediation becausemoderately large coefficients were

evident for the paths from age to the speedvariable and from the speedvariable to the cognitive

variable. Moreover, in each case the direct or

unmediatedrelation betweenage and the cognitive variable was substantially smaller than the

correspondingcorrelation(e.g.,for Ravens,-.30

vs. -.57; for RAVLT, -.33 vs. -.50; and for Block

Design,r: -.23 vs. -.47).

The resultsjust describedclearly indicate that

a substantialproportion ofthe age-relatedvariance in severalcomplex cognitive measuresis

sharedwith simple measuresthat are hypothesizedto reflect how quickly simple processing

operationscan be executed.However,it is important to emphasizethat not all age-relatedeffects on complex cognitive measuresare shared

with simple speed measures.Results such as

those I havejust describedare sometimesmisinterpretedas implying that a single monolithic

factor is responsiblefor all ofthe age differences

observedin measuresof cognition. In fact, an

advantageof thesetypes of correlational proce-

dures is that they allow the relative contribution

of different types of influencesto be determined,

insteadof focusing exclusivelyon whether the

influence of a particular variable is different

from zero, as is often the casewith other analytical procedures.The results of these analyses,

and of similar analysesof other data, suggest

that measuresof simple processingefficiency

share large proportions of age-relatedvariance

with several different types of complex cognitive

variables. They are thus consistent with the interpretation that factors related to processing

speedcontribtte to some of the observedage

differences in variables representinghigher-order cognitive functioning.

Now that the relations involving processing

speedhave been establishedto exist, it is appropriate to ask about the mechanismsthat might be

responsiblefor those relations. I believe that at

least two speed-basedmechanisms,which are

schematically illustrated in the next figure, are

involved in the age-relatedeffects on cognition

(Salthouse,1996).I refer to one mechanismas

the limited time mechanismbecauseif elemen-

Time as a Factorin the Developmentand Decline of Mental Processes

\

Cognition

./

u:,: lirr theinfluenceof

rhc rr'lativecontribution

u!'nccsto be determined

:lu.rr c'lyon whetherthe

lar rrriable is different

e c.r\L'withotheranalytisuli. of theseanalyses,

\ .\j' other data, suggest

le firr)cessingefficiency

variance

i \'l .rge-related

p..r oI complex cognitive

-i c()nsistentwith the inrs rclatedto processing

' n r t r r l ' t h eo b s e r v e da g e

s r!'presentinghigher-orng

rn] lnvolvingprocessing

ishcdto exist.it is approncehlnisms that might be

elltr,rns.I believethat at

mr'chanisms,which are

rd rn the next figure, are

arcJ effectson cognition

ler to one mechanismas

nr\nr becauseif elemen-

tary processingoperationstake longer to be performe4 then fewer of them can be completed in

a given period. This mechanismis likely to be

very important in timed tests, and especially

those with low levels of difficulty in which performance is primarily assessedin terms of the

number of items completed in the specified

time. However, the limited time mechanism

could also affect performance in more complex

situations where a sequenceof operationsmust

be performed and slow executionof the early

operationsmeansthat later, and possibly higherorder,operationsare not successfullycompleted.

A relevantmetaphorfor the limited time mechanism might be an assemblyline in which if early

operations are not completed rapidly, the products at subsequentstagesmay be defective.

Considerableevidenceindicatesthat with increasing age less processing can be accomplished in the same amount of time. For example,this phenomenonis evidentwith manipulationsof stimuluspresentationtime, with posthoc analysesofthe level ofaccuracyobtainedat

specified reaction times, or with functions relating reaction time to the amount of completed

processingor to the number of operationsthat

must be performed.

The secondmechanismby which slowerprocessingcould leadto impairmentsin the quality

of cognitive functioning is known asthe simultaneity mechanism,and it may operateeven when

there are no external time limits. The critical assumption in this mechanismis that in order to be

successfulmany higher-level cognitive operations such as association,integration and abstraction require that all of the relevant information is simultaneouslyavailable.If it is not all

accessiblewhen needed,then the operationsmay

not be completedsuccessfully,and the quality of

the relevant performancewill be impaired. Several factors probably affect the amount of simultaneously available information, but the time to

activatethe information is postulatedto be a particularly important determinant.

It could be arguedthat if information remains

in the samestateof availability indefinitely then

the completionof processingwill merely be delayed when the speed of activation is slower.

However,if information is lost through decayor

displacementthen therewill be a limited period

when all relevant information is available, with

the duration ofthat period dependenton the dynamics of the speedof activation and the rate of

3 t

loss or forgetting.Moreover,becauseit is unrealistic to expect information to remain in a high

stateof availability indefinitely, speedof activation is likely to be a critical variable affecting the

amount of information that is simultaneously

available.

It might still be possibleto achievethe same

eventual level of higher-order products if the

rate of loss of information was slowed to the

sameextentas the rate of activation.However,in

order for this to occur the information must not

be lost as rapidly in older adults comparedto

young adults,and there is no evidenceto suggest

that the rate of forgetting is slower with increasedage. Instead most of the relevant research suggeststhat the rate of forgetting for

older adults is either the sameas that of young

adults, or possibly even faster, but certainly not

slower(seeSalthouse,1992).

Becauseit is difficult to obtain precisemeasuresof the time courseof information availability, very little evidencedirectly relevantto the

simultaneitymechanismis currently available.

Although this mechanismis largely speculative

at the present time, it seems plausible as a

mechanismby which slower speedof processing

could lead to lower levels of cognitive performance.

Summary and ImPlications

I will now summarizethe major points of this

chapter.First, I suggestedthat effective or functional time decreaseswith increasingage, and

that it seemslikely that this decreasehasconsequencesfor many types of cognitive functioning. Second resultsfrom two correlationalprocedureswere describedthat indicate that measuresof processingspeedare closely involved in

the relations betweenage and severaltypes of

cognitive functioning. And thir4 two mechanisms hypothesizedto contributeto the role of

speedon cognition,limited time and simultaneity, were discussed.I believethat the combination of plausible argumenttogetherwith relevant

empiricalevidencelendscredibility to the timebased interpretation of developmentaldifferences in cognition. However, much more researchis clearly neededbefore this interpretation would be completely convincing. For example, more analyticalresearchis desirableon

the mechanismsthat areresponsiblefor the speed

38

Timothy A. Salthouse

T. A. (1992).Influenceof processing

mediation that has been establishedto exist. Fi- Salthouse,

adult age differences in working

on

speed

nally, it is important to capitalize on the strengths

79, 155-170'

Psychologica,

Acta

memory.

of different methodologicalapproaches'because

T. A. (1993). Influence of working

Salthouse,

both correlational and experimental procedures

in matrixreamemoryon adultagedifferences

provide valuable information. For example,corsoning.British Journal of Psychology'84' l7l'

ielational proceduresare useful to estimate the

199.

speedtheory

strength of relevant relations, and experimental Salthouse,

T.A. (1996).Theprocessing

procedures are useful to explore the nature of

ofadult agedifferencesin cognition'Psychological Review,103,403-428.

lhe mechanismsresponsiblefor the relations.

N', & Rhee,S' H. (1996)'

T. A., Fristoe,

Salthouse,

effectson neuropHow localizedareage-related

sychologicalmeasures?Neuropsychology,10,

References

272-285.

R. W., & Johnson,M. B. (1989'1990)'

Woodcock,

speed

(1994).

Processing

T.

A.

Kail"R..& Salthouse,

BatteryPsycho-Educational

Woodcock-Johnson

S6,199asa mentalcapacity.ActaPsychologica,

Allen, TX: DLM.

Revised.

225.

Distortionsof Mr

Elizabeth F. Loftus

A famous story told by Pi

memory distortion has long

tion ofAmerican psycholog

ther research,and so it seen

chapter for a book celebrati

his birth with a reminder ol

ferring to Piaget'sclassic ch

an attemptedkidnapping tha

pened to him early in his

194511962).The false mern

stayedwith him for at least r

"... one

of my fir

date,if it were true. fi

I can still see,most cl

scene, in which I b

about fifteen. I was

which my nurse w

Champs Elys6es, n'l

kidnap me. I was helr

tened round me whil

tried to stand betwec

She receivedvarious

still see vaguely tlx

When I was about fil

ceived a letter from r

shewantedto confess

in particular to retun

been given as a re$an

up the whole story ..

have hear4 as a child

story, which my par

projected into the pa

visual memory."

Piaget'sstory illustrates t

.:eate a vivid memory in tl

.hich is why I found it use

:":rly analysis of the controrn

-cmories (Loftus, 1993).k

: r. false memory appearsto

-:ough a story told at that

::rrugh subsequentfamil,vn

: -estion about the extent ft

:r.ne to forming vivid but u

: rgs that happenedin our p

:-.. who also have used the I