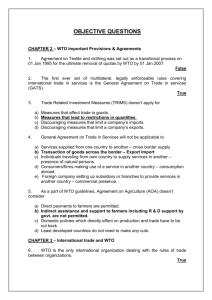

Trade-FDI-Technology Linkages in East Asia

advertisement