National Poverty Center Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy, University of Michigan Non-Standard Work and Health: Who is at Risk and Who... www.npc.umich.edu

National

Poverty

Center

Gerald

R.

Ford

School

of

Public

Policy,

University

of

Michigan

www.npc.umich.edu

Non-Standard Work and Health: Who is at Risk and Who Benefits?

Richard H.

Price, University of Michigan

Sarah Burgard, University of Michigan

This paper was delivered at a National Poverty Center conference.

Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the National Poverty Center or any sponsoring agency.

Nonstandard Work and Health: Who is at Risk and Who Benefits?

Richard H. Price

Department of Psychology

Social Environment and Health Program

Institute for Social Research

University of Michigan

Sarah A. Burgard

Department of Sociology

Population Studies Center

Institute for Social Research

University of Michigan

Paper presented at the conference, “Health Effects of Non-Health Policy”

Bethesda, Maryland

February 9 & 10, 2006

Sponsored by the National Poverty Center

University of Michigan

Ann Arbor, Michigan

1

The last half century has seen a dramatic series of changes in the nature of work in America

(Cooper, 1998; Price, in press). Improvements in the technology to support work promised to ease the burden of jobs, but may at the same time have increased inequality in income (Danziger& Gottschalk,1995) and reduced job security (Rifkin, 1995). A new wave of union management struggles in the1970s and

1980s resulted in lower levels of union membership (Tausig et al, 2004; Murphy, et al, in press) and reduced benefits for American workers. The “enterprise culture” of the 1980s encouraged strong movement for deregulation of American business and privatization of government services. Economic downturns in the 1980s and 1990s produced a wave of downsizing in the manufacturing sector (Baumol et al 2003) and at the turn of the century, we see an increase in the influence of globalization on the American workplace and the “off shoring” of American jobs. Women have entered the American workforce in rapidly increasing numbers (Tausig et al 2004) and families have had to deal with the conflicting and stressful demands of combining family and household responsibilities and work (Guerts & Demerouta, 2003; Hochschild, 1997).

In what follows we briefly consider changes in the nature of work in America that are potentially consequential for the health and well being of working men and women. We then focus on the potential health effects of nonstandard work, offer analyses assessing the way health is related to nonstandard work using the American’s Changing Lives longitudinal survey, and finally consider the policy implications of the rise of nonstandard work for the health of the American workers.

Women in the workforce, job insecurity and a changed employment contract

Women have been entering the workforce in increasing numbers and the consequent changes in work and family life have implications for the health of American workers and their families. A recent national survey of American workers indicates that high workloads and work-family conflict are strong predictors of worker stress (Murphy, in press). Dual earner couples not only must manage two jobs, but household and care-giving responsibilities as well (Geurts and Demerouti, 2003). Bond and colleagues

(1998) report results of a national survey in which 30% of workers experienced a major conflict between work demands and family responsibilities. The evidence suggests that conflict between family

2

responsibilities and work is associated with higher levels of health complaints including backache, headache, and other somatic symptoms, particularly for women (Guerts et al 1999). Allen and colleagues

(2000) also report elevated physical symptoms and distress in couples experiencing work-family conflicts as well as psychological strain and depression. For some women and their families, entry into the workforce will involve increased strain on family and personal resources, while for others paid employment may be a source of satisfaction and fulfillment that outweighs these strains.

Along with demographic changes, downsizing has shifted the composition of the American workforce and increased job insecurity (Baumol, Blinder and Wolfe, 2003). There is evidence that involuntary job loss is associated with declines in the health of workers and their families, including increases in depression, alcohol abuse, anxiety, child abuse and marital conflict (Catalano et al., 1993 a,

1993 b; Price, 1992, 2002; Vinokur et al., 1996). The economic strain accompanying job loss is associated with increases in depression (Kessler et al., 1987, Price et al, 2002; Vinokur et al., 1996) and produces a variety of secondary stressors (Price et al., 1998). In addition, Baumol, Blinder and Wolfe (2003) conclude that downsizing appears to have produced a fall in wages per unit of productivity. While downsizing has been largely confined to manufacturing, employment in other sectors such as the service and retail industries has actually grown in the last two decades. Downsizing might more correctly be thought of as industrial restructuring, as the US economy shifts from full time manufacturing jobs to lower paying, less secure, often part time service and retail jobs.

In addition to the increase in women participating in paid employment, and increases in job insecurity associated with downsizing, employers have changed the nature of the employment contract

(Cooper, 1998; Rousseau, 1995). Rousseau (1995) observes that employer-employee relations have changed from long term, more informal, relationally-oriented exchanges to shorter term, contractual-based arrangements. Standard jobs that promised the exchange of regular pay and benefits for full time work are being replaced by lower-paying part time or other nonstandard jobs with fewer or no benefits, fewer health and safety protections, and less job security (Kalleberg, 2000). In response to increased competitive pressures, to accommodate absences, and to increase workforce flexibility, employers have adopted a

3

number of practices to restructure standard employment into part time and contingent jobs (Houseman,

1999). This “just in time” workforce strategy is an important contributor to the working conditions that nonstandard workers often face and is a new and important feature of American working life, with important implications for the health and well being of workers and their families.

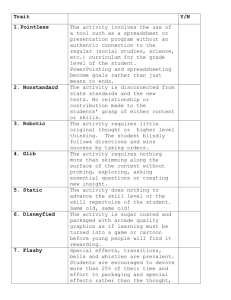

Nonstandard work, “bad jobs”, and health

In the past several decades firms have increasingly pursued more flexibility in their employment relationships, separating employees into a core group with standard, continuous and secure jobs, and a peripheral group employed in involuntary and at-will “nonstandard” jobs (Tilly 1996). A commonly-used definition of standard work characterizes it as full-time, typically on a fixed schedule, with the expectation of continued employment, and at the employer’s place of business under the employer’s direction

(Kalleberg 2000). Nonstandard work then encompasses alternate employment relationships that vary on these bases, including on-call work and day labor, temporary-help agency employment, employment with contract companies, independent contracting, other self-employment, and part-time employment in otherwise “conventional” jobs (Kalleberg, Reskin and Hudson 2000). By one measure, these categories taken together made up almost 30% of the U.S. workforce in 1995 (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 1997).

Nonstandard arrangements were common until World War Two, declined in the growth years of the 1950s through the mid-1970s, then reemerged in the late 1970s and appear to have been growing in importance since then (Blank 1998; Polivka and Nardone 1989). Increased global competition and pressures for cost reduction clearly played a role in increases in nonstandard work arrangements. In particular, temporary employment has grown about 11% per year since the early 1970s (Segal and Sullivan

1997), and part-time employment rose from about 16 to 18% of the labor force between 1970 and 1990, mostly due to growth in involuntary part-time work (Tilly 1996). The growth of temporary jobs has increased more than fourfold since the early 1980s, from 0.5% to 2.3%, while the level of self-employment has stayed stable or declined (Hudson 1999). What appears to make the contemporary situation unique is

4

the proportion of newly-created jobs that are nonstandard (Cappelli et al. 1997), many of which are in the service sector.

Two explanations have been forwarded for the increase in nonstandard work. The first highlights employers’ use of these kinds of arrangements in response to the requirements of lean production in a globalizing economy, where nonstandard workers can be easily hired and cut in response to demand. An alternate explanation is that employers are accommodating worker preferences as the labor force becomes increasingly female and workers juggle other, often caretaking, responsibilities. Both sides of the argument offer some evidence; on the one hand, high proportions of temporary help agency employees would prefer a standard contract, and are thus involuntary nonstandard workers (Kalleberg et al. 1997). Coupled with the relatively high growth in this form of nonstandard work, the evidence suggests that employers’ preferences are responsible for the increase in temporary agency work, not worker preferences (Goldman and

Appelbaum 1992; Kalleberg, Reskin and Hudson 2000). Furthermore, in some studies businesses have cited the cost savings of not providing benefits as a reason for using nonstandard workers (Houseman

2001), indicating that nonstandard work could be good for employers but bad for employees.

On the other hand, studies have shown that two types of nonstandard workers, self-employed people and independent contractors, are less likely to have fringe benefits but earn more than workers in standard jobs and on average, prefer their arrangements to a standard job (Kalleberg et al. 1997; Polivka

1996). Preferences for nonstandard work contracts may be also higher among young families, people nearing or past the legal retirement age (Christensen 1990; Wenger and Appelbaum 2004), and people with disabilities (Schur 2003), and these populations may be healthier under such arrangements (Isaksson and

Bellagh 2002). Nonetheless, there is considerable debate about how much individual choice nonstandard workers, and women in particular, exercise in accepting nonstandard work contracts, and how much they are channeled into these forms of work due to the constraints of a stratified labor force (Walsh 1999).

It is clear that there is considerable heterogeneity in the characteristics of nonstandard jobs and their incumbents; one study finds that while there are high- and low-wage jobs available to contract

5

workers and the self-employed, temporary-help agency employment, on-call/day labor, and part-time work tend to be associated with worse characteristics both in terms of working conditions and available benefits than are standard full-time jobs (Kalleberg, Reskin and Hudson 2000). Furthermore, nonstandard work is concentrated among women (Amott and Matthaei 1991), and within the nonstandard work arena, women are particularly likely to be in part-time jobs (Kalleberg et al. 1997; Nollen 1996), while minority women and those of low economic standing are overrepresented in the poorest nonstandard work arrangements

(Nollen 1996). The diversity of nonstandard work arrangements and their uneven distribution across the working population suggest that the health-related consequences of nonstandard working arrangements are likely to be complex.

Despite the fact that nonstandard work accounts for an increasing fraction of the occupational opportunities in this country, we know relatively little about the potential consequences for health and existing evidence is not unequivocal. In some studies, nonstandard employees reported greater psychological distress and to a lesser extent, poorer physical health than standard employees (Benach et al.

2004; Dooley and Prause 2004; Friedland and Price 2003; Virtanen et al. 2005a). Nonstandard workers have also shown a higher risk of mortality than permanent employees, but lower risk than the unemployed, while those who moved from a temporary to permanent position had the lowest risk of mortality, even controlling for socioeconomic differences (Kivimaki et al. 2003). Nonstandard employees are at risk of deterioration in occupational health and safety in terms of injury rates, disease risk, and hazard exposures

(Quinlan, Mayhew and Bohle 2001), even net of controls for worker’s personal characteristics, family status, occupation and industry (Kalleberg, Reskin and Hudson 2000). Nonetheless, there are important health variations across different types of nonstandard workers between, for example, on-call or substitute workers versus those on temporary but full time contracts that otherwise resemble permanent jobs

(Virtanen et al. 2003b; Virtanen et al. 2005b). Other studies find that individuals in nonstandard contracts are as physically healthy or healthier than their peers who work under standard arrangements (Bardasi and

Francesconi 2004; Virtanen et al. 2003a; Virtanen et al. 2002), though they may report greater job dissatisfaction, fatigue, backache and muscular pains (Benavides et al. 2000). Part-time work has even

6

appeared to be protective for women in some studies (Bardasi and Francesconi 2004; Nylen, Voss and

Floderus 2001).

The lack of clear consensus on the health effects of nonstandard work could result from the variety of circumstances under which people accept and perform nonstandard work. First, various forms of selection may influence the empirical results, aside from the impact of working arrangements themselves.

Nonstandard workers may have poorer subsequent health because they differ from standard workers on set of baseline characteristics and resources than predict health independently of working conditions (Benach et al. 2002; Benach et al. 2000). For example, women, racial/ethnic minority group members, and people of low socioeconomic position have traditionally been more likely to work under nonstandard arrangements

(Hipple 2001), and these groups often report poorer health than white men and people of higher social status. In addition, people in poorer health to begin with may be more likely to be hired for a nonstandard position than a standard job (Schur 2003), and their subsequent health outcomes will be poorer at least in part because of earlier health deficits. Second, some people are compelled to take nonstandard jobs for lack of other opportunities, due to deficiencies in the qualifications employers demand, such as education or relevant skills; for these individuals we would expect the negative health consequences of nonstandard work to be greatest.

Workers with few options on the labor market may be compelled to take nonstandard jobs characterized by both relatively low control and high demands (Karasek, 1979; Taylor and Repetti (1997), conditions that produce chronic stress and trigger health problems. These are often jobs involving irregular hours, split shifts, and necessitating rapid rearrangement of family life schedules (Zeytinoglu et al, 2004).

Some workers may also be compelled to combine two or more nonstandard jobs to increase earnings.

Third, the lack of available benefits can play a role in health outcomes for nonstandard workers; nonstandard workers and their families have much lower rates of health coverage than workers with standard jobs (Distler et al 2005). Lack of health insurance can be risky when neglect of acute health problems can lead to chronic complications (Institute of Medicine, 2001). Finally, and in contrast to workers who would prefer standard work but are unable to obtain it, some workers may prefer nonstandard

7

arrangements and suffer few health consequences. For example, some nonstandard workers may have access to protective resources, such as a partner with higher earnings and benefits, which could buffer the potential resource deficits associated with nonstandard jobs. In addition, some nonstandard workers are younger people combining work with school or other responsibilities, and are resilient because of their age.

Nonstandard working arrangements and health: An Empirical Examination

Here we present a brief description and analysis using a nationally-representative sample of

American workers to illustrate relationships between nonstandard working arrangements and health among men and women, to consider the importance of stated preferences for nonstandard work, and to illustrate the importance of considering selection into different types of work on the basis of health and other characteristics. The data we employ here from the Americans’ Changing Lives (ACL) study are highly suited to the present analysis because we can observe workers in different nonstandard employment arrangements over long periods of follow-up, we can distinguish workers who report that they prefer parttime employment from those who would rather work full-time, and because we have information on several health outcomes as well as health “shocks” that occur between survey waves. These features of the data make our study unique, as careful assessment of selection as well as stated preferences for nonstandard work are not typically included in existing studies.

Data and Methods

The ACL study is a longitudinal cohort comprised of a stratified, multi-stage area probability sample of non-institutionalized adults 25 years and older, with over-sampling of adults 60 and older and of African

Americans. Weights have been designed to make the ACL respondents representative of the noninstitutionalized population in the contiguous United States in 1986. In the baseline survey in 1986, face-toface interviews were conducted with 3,617 men and women (representing 70% of sampled households and

68% of sampled individuals), and these individuals were followed up with subsequent waves of data collection in 1989, 1994 and 2001/2 with a response rate among survivors of about 78% at the last wave.

The ACL was designed to collect longitudinal information about the independent and combined effects of a

8

wide range of psychosocial risk factors on health and on social disparities in health. Further information about the longitudinal study design for the ACL can be found elsewhere (House et al. 1990; House et al.

1994).

The central indicator in the analysis is employment type, which distinguishes between respondents doing standard work (35 or more hours per week) and those doing nonstandard work, categorized as (a) voluntary part time workers, who prefer to (and do) work less than 35 hours per week, (b) involuntary part time workers, who work part time but would prefer to work more hours, and (c) respondents who report that they are self employed (regardless of number of hours worked per week).

1

At baseline in the ACL study, about 63% of working women hold a standard job, while about 16% are voluntary part time workers,

7% are involuntarily working part time, and about 14% are self employed. Among working men, just over three-quarters are working in standard jobs and another 19% are self employed, while only 2% are voluntary part time workers, and about 3% are involuntarily working part time. This gender difference reflects the much longer history and social acceptability of female part time employment. We would prefer to include a more diverse array of nonstandard work types, some of which would include larger groups of men, but focus here on the key categories distinguishable in these data and on women, who dominate nonstandard work arrangements (Virtanen et al. 2005b).

2

We estimate prospective models of employment type and health; first we create a “stacked” data set with up to three person-spell observations per respondent.

3

The first potential person-spell, for example, contains information about background characteristics and health in 1986 and employment type and health in 1989, as well as health shocks that occur in the interim. The second and third person-spells include the

1

An analysis using Current Population Survey data has shown that classifying workers as “involuntary part time” on the basis of their reported hours and reasons for not working at least 35 hours per week does reflect “involuntary” part time work (Stratton 1996). In the present analysis an employment type indicator was created for each survey wave using answers to questions about the number of hours the individual was currently working, whether she would prefer to work more hours, and the sector of employment (private,

2 public, or self employed).

We consider self employment as well as the part time employment categories for men in our analysis, but the small numbers in part-time work reduces our ability to ascertain statistically significant differences from standard workers.

3

Breaking the information into multiple observations per individual allows us to take advantage of all the information on work and health that is available, even if a respondent leaves the sample at some point over follow-up.

9

equivalent information for the 1989–1994 and 1994–2001/2 periods. Using this analytic sample of personspells, we estimate multinomial logistic regression models predicting employment type as a function of earlier sociodemographic, work and health characteristics.

4

We then estimate OLS regression models of self rated overall health, depressive symptoms, and body mass index as a function of earlier employment status and health. Models are estimated using Stata 9.0SE, adjusted for the multiple observations per individual.

5

All models also include an indicator (not shown) for the number of years in the person-spell under observation.

Descriptive Results

Descriptive data for selected measures used in the analysis are presented in Table 1, separately by sex and by the type of employment reported by the respondent at baseline. Like other studies, we find significant differences in the average age, racial group, marital status, educational attainment, annual income, and number of hours spent caring for children among respondents reporting different types of employment. To highlight some of the differences, voluntary part time and self employed workers are older than others, while black men and women are less likely than non-blacks to be self employed. For women, the amount of childcare is higher among part time workers, while among men, part time and self employed workers report less childcare than those in standard work. Among women, average schooling is lowest among the involuntary part time workers and highest among standard workers. Men voluntarily working part time have the lowest average educational attainment in this sample, with self employed men reporting the most education. Regardless of sex, involuntary part time workers report the lowest annual household incomes. Turning to job characteristics, many women work in service industries, with the highest fraction among voluntary part time workers. Voluntary part time male workers are also most likely to work in a service industry, while those in standard employment arrangements are least likely to do so. Job

4

We only use person spells from 1986-1989 and 1989-1994 for these models, as questions about preferred

5 hours of work were not asked in 2001.

We tested for potential effects of selection out of the analytic sample due to survey non-response or death by estimating a series of multinomial logistic regression models of health that included alternate categories for survey non-response and death. We found that employment type was not a statistically significant predictor of non-response or death when we included the covariates in the OLS models of health presented here.

10

dissatisfaction (1 = lowest, 5 = highest) is highest among involuntary part time women and lowest among the self employed, while differences across employment types are not statistically significant among men.

Baseline health differences are a potentially important source of differences in health over follow up. Respondents were asked to rate their overall health at the time of the survey with the typical five category item for self-rated health, with values ranging from excellent (1) to poor (5). While there are no significant differences in average self-rated health across employment types among women in 1986, men voluntarily or involuntarily working part time have significantly worse self-rated health than others.

Depressive symptoms are measured using an 11-item subset of the Center for Epidemiological Studies

Depression Scale or CES-D (Radloff 1977). For both women and men, involuntary part time and standard workers showed more depressive symptoms than voluntary part time and self employed workers in 1986.

As a final measure of health we consider body mass index (BMI), calculated as an individual’s weight in kilograms divided by their squared height in meters. There are no significant differences in baseline BMI for men or women in the ACL sample, but all groups fall into the “overweight” category, or just below it.

Finally, Table 1 shows the proportion of respondents who reported in 1989 that they had experienced a negative health shock or an involuntary job loss since 1986.

6

There are no significant differences in the frequency of health shocks across groups for this period, but among men involuntary job losses in the three years after baseline were significantly more common for involuntary part time workers.

Who Does Nonstandard Work?

We turn from these cross-sectional relationships to a prospective examination of the predictors of nonstandard work arrangements. Table 2 shows unstandardized coefficients associated with predictors from multinomial logistic regression models of employment type, separately for women and men. In these prospective models, many of the same relationships between predictors and type of employment arrangement that were apparent in the cross section (in Table 1) persist. We highlight only a few of the results here; first, black women are less likely than white women to be working part time voluntarily, even

6

The definition of a “serious” or “life-threatening” life event was left to the respondent, so there may be some variation in the objective severity of the event; however, in the present analysis we assume that any self-reported serious or life-threatening event could potentially impact an individual’s employment type or subsequent health.

11

net of other predictors. Married women are more likely to work part time (either voluntarily or involuntarily) than unmarried women, while married men are significantly less likely to involuntarily work part time. Women reporting more annual childcare hours are more likely to subsequently work part time, with no such effect among men. Men who weren’t working at the baseline of the person-spell under consideration are considerably more likely to be working part time than to be in a standard job at follow-up.

In these models we do not find any significant effects of baseline health or health shocks over follow-up on employment type, though in simpler models poorer baseline health increased the likelihood of working part time at follow-up. Finally, having lost a job involuntarily in the past three years is associated with a significantly greater likelihood of involuntary part time work at follow-up among men.

The cross-sectional relationships from Table 1 and the prospective results from Table 2 show that there are important differences in characteristics across different work types. Self employed workers appear to be similar to standard workers in terms of their resources and well-being, while involuntary part time workers are considerably worse off. Voluntary part time work is a relatively common choice for women, and is associated with higher baseline household incomes and greater satisfaction at work than among standard workers, though voluntary part time workers are older than standard workers. Among men, voluntary part time work appears to be the domain of men nearing retirement, who are in worse overall health at baseline because of their age, but report higher job satisfaction and lower depressive symptoms than standard workers.

Does Nonstandard Work Influence Subsequent Health?

We now turn to models that estimate the impact of employment type on subsequent health. Tables

3 through 5 show the results of OLS regression models of overall self-rated health, depressive symptoms, and BMI, separately for women and men. We only summarize the results of these models here, but all effects are presented in Tables 3 through 5. Table 3 shows results for models of overall self-rated health; we find that self employed women have significantly better self-rated health than standard workers, while men who voluntarily work part time have significantly worse self-rated health than their counterparts in standard employment arrangements. Differences across groups of workers in sociodemographic

12

characteristics account for some of the health advantage of self employed women and the health disadvantage of voluntary part time men, while further controls for work characteristics in Model 3 do not further affect the results. Adding controls for baseline health and health events over follow up in Model 4 considerably weakens the health advantage of self employed women, though it is still significant, while these factors explain the remaining differences across male employment groups.

Turning to a measure of psychological health, Model 1 in Table 4 shows that women voluntarily working part time have significantly lower depressive symptoms than standard workers. Among men, involuntary part time workers report more depressive symptoms than standard workers, though the difference is only marginally statistically significant. Differences in sociodemographic characteristics don’t explain much of the health advantage of voluntary part time women, but account for much of the disadvantage of involuntary part time men. Differences in work characteristics don’t account for the lower depressive symptoms of voluntary part time women, but the difference is significantly reduced when we consider depression at the baseline of the person-spell and health shocks over follow-up.

Finally, Table 5 shows results for models of body mass index; here the only significant effects we observe occur among women. Model 1 shows that women voluntarily working part time and self employed women have significantly lower body mass indexes than their counterparts in standard employment relationships. With adjustments for sociodemographic characteristics in Model 2, the differences are reduced and self employed women no longer significantly differ from standard workers. Sociodemographic differences explain a small portion of the BMI advantage of voluntary part time workers, but a much larger fraction of the difference is explained by baseline BMI and health shocks over follow-up. Nonetheless, women voluntarily working part time show increases in body mass index over follow-up about one-half point lower than the increase among women working under standard arrangements, a non-trivial difference.

We also tested a series of interactions (not shown) to further explore potential differences within categories of nonstandard workers. Focusing on women, we found that the lower depressive symptoms shown by voluntary part-time workers were restricted to those women who reported childcare

13

responsibilities; the greater the number of annual childcare hours, the more strongly part-time work was associated with better mental health. In addition, the interaction models revealed that women with childcare responsibilities had better self-rated health if they worked part time voluntarily rather than working a standard job, an effect obscured in the full model. We also found that the lower BMI of self-employed workers was limited to unmarried women, those with low household incomes, and/or those in blue collar positions. For more socially-advantaged and married women, self-employment was not associated with lower body mass index. Finally, there were suggestive indications that voluntary part-time work was associated with lower depressive symptoms among married, but not unmarried women, and that involuntary part-time work was not as strongly associated with depressive symptoms among lower-income women, compared to those with higher household incomes. These differences across groups of nonstandard workers highlight the variation in circumstances that produce health-enhancing or health-damaging conditions, and suggest the importance of overall socioeconomic and family characteristics as the context for nonstandard work.

Overall, our brief analysis has shown that nonstandard work arrangements can have effects on subsequent health, even when we take into account the differences across groups of workers at baseline.

Self-employed women report better self-rated health than standard workers in our full models. It is also important to consider an individual’s stated preference for work hours; here, we find that women working fewer than 35 hours per week have lower depressive symptoms and lower body mass indexes than standard workers, but only if they prefer to work part time. Relatively few men work in part-time arrangements and the differences we observe in their subsequent health are fully explained by their baseline social and health disadvantages. However, this analysis supports other work suggesting that are important differences even within groups of nonstandard workers (Virtanen et al. 2005b); for example, we found that the health advantages observed for women voluntarily working part time were restricted largely to those with childcare responsibilities.

We briefly explored some potential explanatory mechanisms for relationships between nonstandard work and subsequent health. One often-cited mechanism is the perceived job insecurity faced

14

by many nonstandard workers; we found that self-reports of job insecurity were associated with subsequent health but did not explain the impact of nonstandard work. We also examined detailed job titles of workers in different employment type categories to see whether there were large differences in the work done by voluntary part time and self employed women that set them apart from standard workers. In general, it does not appear that standard workers or voluntary part time workers have clearly superior jobs in terms of prestige or working conditions. However, self employed women were more distinctive, with large fractions working as managers or administrators, private child care workers, hairdressers and dressmakers. These job titles suggest a considerable amount of control over working conditions and possible ownership of a business.

However, what we are unable to examine in the present analysis may also be interesting. We do not have indicators of important mechanisms like health care insurance coverage, but can infer that a substantial fraction of these nonstandard workers don’t have health coverage. We do, however, have indicators in our models of negative health events over follow up, and the models show quite clearly that these have a major influence on health decline over follow-up. Whether they are the consequence of nonstandard work arrangements or are unrelated events, such shocks would be a much greater burden for those without health care benefits. Along with baseline health, these shocks greatly reduce the observed health advantages for women who choose to work part time and for self-employed women. Taken together with our other findings, this suggests that a worker’s family circumstances and health history strongly condition the effects of nonstandard work on subsequent health, and that these complexities need to be considered as policies are developed to fit the changing workforce.

Policy Reforms to Protect Nonstandard Worker’s Health: Old assumptions, new reality.

Facing increasing global competition and pressures for economic efficiency, employers have responded in a number of ways. One adaptation has been to change the composition of their labor force, employing more nonstandard workers, which reduces the cost of paying benefits to employees (Houseman,

15

1999). Although both nondiscrimination laws in the tax code and the Employee Retirement Income

Security Act of 1974 are intended to cover a wide range of working arrangements, these legal requirements can be avoided in many cases by hiring nonstandard workers who are not explicitly covered under the laws.

Nonstandard work arrangements are becoming more common in the United States and the prospects are that the number of these kinds of jobs will continue to grow. These are jobs that may be of limited duration, can offer lower pay, and seldom provide mobility to full time employment with better pay and benefits. On the other hand, some groups in society will benefit from these more flexible arrangements.

Below we will briefly consider policy implications for the health and well being of both those potentially disadvantaged by nonstandard work arrangements and some potential beneficiaries.

Women have entered the workplace and traditional gender based work and family roles have changed. Women have entered the workforce in increasing numbers in both standard and nonstandard work arrangements, but nonstandard work arrangements are dominated by women. Some groups of women, particularly those with childcare responsibilities, those who report that they prefer nonstandard arrangements, and those who are self-employed, appear to benefit from their working arrangements. At the same time, the lowest paying part time nonstandard jobs employ 58 % of all nonstandard workers and 81% of all women in nonstandard work (Kalleberg, et al 1997).

Ackers (2003) observes that family roles and responsibilities are structurally connected to patterns of paid employment, but whether this is explicitly acknowledged or not depends on the perspective of the employer or employee and the national policy context. For example, Acker observes that three patterns of policy orientation prevail in Western Europe. First, in the Scandinavian countries, employment and family policies are already "intertwined" and have wide acceptance. Second, in other countries there is already a policy agenda emerging that focuses on improving work life balance through flexible scheduling, parental leave and childcare. Still other countries regard family policy and employment policy as entirely separate domains of policy development. The current policy climate in the United States appears to resemble the second pattern, with employers beginning to establish work family programs.

16

Work family programs initiated by employers have become much more prevalent in the United

States over the last twenty years (Murphy & Sauter 2004). They may emphasize flexible work schedules, childcare provisions, job sharing, or provisions for eldercare, and employers regard such programs as effective recruitment tools. However a key unresolved issue is how effectively the programs are actually implemented (Geurts & Demerouti, 2003), and whether they will be made available to nonstandard workers who may need them as much as, or more than standard workers, especially if they are holding more than one part time job to maintain a workable family income.

Nonstandard work arrangements may be preferred by some groups and have no negative impact on health and well being. Our analyses suggest that part time nonstandard work arrangements may be preferred by some groups with family responsibilities and may even provide some benefits to health and well being. In addition, we note that many workers in nonstandard work arrangements may have had health problems in the past. Indeed, nonstandard work may be particularly well suited to persons with disabilities.

Schur (2003) reports that workers with disabilities in the United States are about twice as likely as nondisabled workers to be in nonstandard work arrangements, including contingent and part time jobs. This overrepresentation of disabled workers in nonstandard jobs might be explained either by labor market barriers for disabled workers, such as reluctance of employers to hire disabled workers in full time jobs, or because of earning limits placed on the disabled by public disability income programs. On the other hand, the overrepresentation of disabled workers could be explained by the fact that nonstandard jobs can provide opportunities to disabled people by accommodating health problems and other personal concerns.

Analyses of the Current Population Survey (CPS), the Survey of Income and Program

Participation (SIPP) and a special household survey of people with disabilities by Schur (2003) indicate that it is not employer discrimination or earnings limits that lead disable persons to be overrepresented in nonstandard work arrangements. Instead, standard full time employment is difficult or impossible for many disabled people, and nonstandard jobs enable many disabled people to work who otherwise would be unable to do so. Some of these jobs can provide on the job training and income and overcome the social

17

isolation experienced by many disabled people. Schur suggests several policies would be helpful for disabled workers including flexible scheduling to accommodate episodes of illness and additional sick leave, both of which might be encouraged by providing tax incentives to employers. In addition while employers may be reluctant to make accommodations for disabled workers, low cost accommodations could be encouraged and well as extended Medicare coverage

Long term employment relationships are becoming less common but policy lags behind labor market reality. A number of government insurance programs have eligibility thresholds based on earnings and work duration that will disqualify workers with nonstandard work arrangements from eligibility. These programs were developed on the assumption that eligible workers would have secure “attachment to the workforce”. Irregular and part time work disadvantages workers in eligibility for pensions, and in terms of training needed to obtain secure jobs in the future. Because some forms of nonstandard work imply movement from job to job, the chance to accumulate enough seniority with any particular firm is sharply reduced. With this mobility comes a reduction in the likelihood that a nonstandard worker will qualify for a pension upon retirement. Furthermore, under federal regulations covering pensions, those who frequently change jobs will have greater difficulty qualifying for retirement plans created by employers. Opportunities for training are also curtailed by nonstandard work arrangements. As technological changes in the nature of work continue to place greater demands on worker skills, continuous training to upgrade skills becomes even more essential to secure high quality jobs (Houseman, 1999).

Workers earning low wages or working part time are much less likely to qualify for unemployment insurance even though they face a higher risk of being laid off. Laid off workers must meet two requirements to be eligible for unemployment insurance: they must have sufficient past earnings and in many states they must have held full time work for a specified period of time, in addition to being engaged in seeking full time work. According to the Economic Policy Institute (2004) half of the states in the U.S. currently deny unemployment insurance to part time, full year workers earning the minimum wage. A strong assumption underlying the Unemployment Insurance program is that benefits should be provided to workers with a strong attachment to the labor force. The Economic Policy Institute suggests several policy

18

remedies including unemployment insurance eligibility based on hours rather than wages, increase in the minimum wage, or loosening the UI eligibility requirements so workers would not be required to seek full time work. Brunner and Colarelli (2004) suggest that one reform in the unemployment insurance system could involve creating individual unemployment accounts. Both workers and employers would make contributions to the unemployment accounts system. Workers could use the resources in these accounts not only for financial support for families during periods following involuntary job loss, but also could use these to take advantage of opportunities for job training, or to meet family responsibilities. Employers would benefit because they would have more flexibility in planning layoffs and retirements if they knew that some employee groups had the security of large individual unemployment accounts.

Health insurance benefits are becoming less common for standard employees and even less so for nonstandard workers. Because the United States does not have a policy of universal health insurance for its citizens, having a job that carries health insurance as a benefit is one of the most important protections for the health of American workers. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) of the National Academy of Sciences

(2001) recently conducted a study that makes it clear that workers who do not have access to health insurance as an employment benefit are vulnerable to health risks both for themselves and their families in a number of ways. Uninsured workers are much more likely to fail to seek needed health care when they need it, often turning treatable acute conditions into chronic health conditions that are much more difficult and expensive to treat. Children are also vulnerable since eight out of ten uninsured children in the United

States live in working families. Younger workers between 19 and 30 are vulnerable because they are often not eligible for health insurance.

Distler, Fisher and Gordon (2005) report that access to employer provided health insurance is declining for both workers with standard and nonstandard working arrangements. Those with coverage still face with increased co-payments, premiums and deductibles. Workers with nonstandard arrangement s are most vulnerable. Analysis of the Contingent Work Supplement of the Current Population Survey by Distler and colleagues (2005) indicates that in 2001, 74% of standard workers had health insurance through their jobs but only 21% of nonstandard workers had such coverage. Families were also affected, with spouses

19

and children of nonstandard workers covered at only one third of the rate of families of workers with standard employment. Uninsured persons are clearly vulnerable both to less adequate access to health care and at least some groups have poorer health outcomes. Uninsured persons are less likely to have less access to health care. Compared to insured persons studied over a two year period, uninsured persons had more difficulty with access to health care. On the other hand, those previously uninsured that gained insurance during the same period showed improvement on a number of measures of measures of access to care

(Kasper, Geovannini & Hoffman, (2000). In addition, compared to continuously-insured middle aged persons, those who were only intermittently uninsured were more likely to have a major decline in health over a four year period (Baker, Sudano, Albert, Borawski, & Dor, 2001).

20

Table 1. Means or Percentages for Independent Variables by Employment Type in 1986, ACL Men and Women.

Standard

Prefers

Part

Time

Women

Part

Time,

Prefers

More

Work

Self

Employed

39.7 45.7 40.4 45.3 pvalue for diff.

Standard

Prefers

Part

Time

Men

Part

Time,

Prefers

More

Work

Self

Employed

<.001 39.2 59.3 38.7 45.4

Annual childcare hours 1986 (in

100s)

14.2 7.28 16.4 5.36

60.7 78.9 67.3 75.4

8.17 10.4 10.2 7.67

<.001 11.0 23.0 10.1 5.62

<.001 76.6 73.0 49.5 79.0

0.005 pvalue for diff.

<.001

<.001

0.005

<.001

Years of education

Total annual houshold income 1986

(in 2005 dollars)

% Blue collar job 1986

% Manufacturing industry 1986

% Service industry 1986

Dissatisfaction with work 1986

(1=low, 5=high)

Self-rated 1986

(Table continued below.)

13.3 12.9 12.5 12.8 0.001 13.1 12.1 12.6 13.4 0.004

(37,014) (44,865) (31,407) (60,055) (40,674) (23,246) (19,333) (55,816)

27.5

18.3

27.2

40.5 70.2 47.7 49.1 <.001 18.4

2.23 1.93 2.49 1.83

53.7 27.2 37.4

<.001 2.13 1.86 2.42 2.02

<.001

0.233

(1.01) (0.836) (1.15) (0.820) (0.911) (0.907) (0.710) (0.963)

2.05 2.01 2.20 2.01 0.442 1.96 2.58 2.21 2.00 <.001

(0.914) (0.877) (0.834) (0.859) (0.872) (1.08) (1.23) (0.937)

2.87

41.5

3.77

41.1

4.11

0.005

<.001

51.7

33.9

54.0

0.00

71.5

13.0

35.5

8.01

<.001

<.001

21

Table 1, continued. Means or Percentages for Independent Variables by Employment Type in 1986, ACL Men and Women.

Depressive Symptoms Score 1986

Standard

Prefers

Part

Time

Women

Part

Time,

Prefers

More

Work

Self

Employed pvalue for diff.

Standard

Prefers

Part

Time

Men

Part

Time,

Prefers

More

Work

Self

Employed pvalue for diff.

Body Mass Index 1986

% with Health Shock 1986-1989

% with Involuntary job loss 1986-1989

24.6

20.1

24.6

21.1

25.7

27.7

24.8

23.9

0.678

0.578

0.260

26.0

19.3

28.2

28.9

26.1

30.5

26.8

15.1

0.360

0.429

0.013

N 609 160 72 130 673 29 31 161

Notes: Standard errors associated with variable means presented in parentheses. Figures based on weighted data, except for column totals. Kruskal-Wallis or

Chi-Square tests for difference between categories of employment type were conducted separately for men and women with significance levels at the * p <

.05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001 levels and are presented in the final column for each sex.

22

Table 2. Unstandardized Coefficients from Multinomial Logistic Regression Models of Employment Type (at t+1) on Selected Independent Variables (at t), Compared with Standard Employment.

Prefers

Part

Time

Women

Part

Time,

Prefers

More

Work

Self

Employed

Prefers

Part

Time

Men

Part

Time,

Prefers

More

Work

Self

Employed

(0.012) (0.017) (0.014) (0.024) (0.022) (0.012)

Married

Annual childcare hours (in

100s)

Years of education

Total annual household income

(started log)

Blue collar job

Manufacturing industry

Service industry

Not working at start of spell

Depressive Symptoms Score

Body Mass Index

Health Shock between waves

(Table continued below.)

(0.290) (0.304) (0.317) (0.617) (0.494) (0.363)

(0.277) (0.298) (0.331) (0.563) (0.468) (0.291)

0.046*** 0.037* 0.011 -0.045

† -0.067 -0.029

(0.013) (0.018) (0.017) (0.027) (0.043) (0.020)

-0.048 0.036 -0.120

† -0.089 0.100 -0.063

(0.056) (0.086) (0.063) (0.092) (0.088) (0.062)

0.194 -0.450* 0.394

† -0.413 -0.882*** 0.495

†

(0.178) (0.191) (0.236) (0.283) (0.198) (0.278)

0.939** 0.918* 0.841** -0.891 -0.419 -0.113

(0.331) (0.423) (0.323) (0.560) (0.501) (0.302)

-1.28* -1.14 -1.09* -1.38* -0.826 -0.897**

(0.603) (0.722) (0.548) (0.641) (0.605) (0.334)

0.479

† 0.325 0.037 0.483 0.548 0.790**

(0.277) (0.403) (0.293) (0.499) (0.561) (0.295)

0.423 0.419 -0.624 2.49** 2.11** -1.16

(0.412) (0.521) (0.478) (0.899) (0.667) (0.747)

-0.055 0.215 -0.219 0.228 0.105 -0.076

(0.122) (0.166) (0.151) (0.261) (0.269) (0.142)

-0.187 0.120 -0.156 0.014 -0.112 -0.079

(0.114) (0.115) (0.138) (0.282) (0.310) (0.133)

-0.039 -0.036 -0.036 -0.093 0.037 0.025

(0.033) (0.038) (0.030) (0.073) (0.038) (0.026)

23

Table 2, continued. Unstandardized Coefficients from Multinomial Logistic Regression Models of

Employment Type (at t+1) on Selected Independent Variables (at t).

Involuntary job loss between waves

Constant

Prefers

Part

Time

Women

Part

Time,

Prefers

More

Work

Self

Employed

0.348 0.461 -0.367

-2.65 1.51 -2.65

Prefers

Part

Time

Men

Part

Time,

Prefers

More

Work

4.05 3.98

†

Self

Employed

0.591 1.25* -0.015

(0.405) (0.486) (0.484) (0.621) (0.599) (0.370)

-5.97*

N (observations)

N (individuals)

1408

870

1177

696

Wald Chi

2

Pseudo R

2

0.120

Note : Coefficients obtained from multinomial logistic regression models, with standard errors of estimates in parentheses, and significance levels denoted by † p < .10, * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001. Models include an indicator for the number of years in the person-spell (not shown), and are adjusted for repeated observations on the same individual. In the started log transformation of income, a positive constant ($500) is added to each respondent’s annual household income before taking the log; individuals with a score of zero on the measure are therefore retained.

24

Table 3. Unstandardized Coefficients from OLS Regression Models of Self-Rated Health on Employment Type and Selected

Independent Variables.

Model 1

Employment type [Standard omitted]

Prefers Time

Women

Model 2 Model 3

Model

4

Model

1

Men

Model 2 Model 3 Model 4

0.283* 0.250

† 0.260

† 0.189

(0.131) (0.130) (0.135) (0.136)

0.034 0.139 0.140 0.131 0.092 Part Time, Prefers More 0.170 0.058 0.034

(0.172) (0.155) (0.158) (0.147)

Self Employed -0.248** -0.214* -0.211* -0.127* -0.092 -0.065 -0.035 -0.034

(0.076) (0.075) (0.074) (0.049)

(0.003) (0.003) (0.003) (0.002)

Childcare hours (in 100s)

Years of education

Total annual houshold income (started log)

Blue collar job

Manufacturing industry

Service industry

Dissatisfaction with work

(1=low, 5=high)

Not employed at follow-up

(Table continued below.)

--

--

--

--

--

(0.055)

(0.054)

-- -0.006

† -0.006

† -0.004 -- -0.005 -0.004 -0.004

-0.036*

--

--

--

-0.035* -0.026*

-0.176** †

0.105 0.114*

0.032

0.092

0.021

0.068

--

--

-0.055*** -0.056*** -0.027*

-0.013 0.006 0.031

-- -- -0.003 0.048

(0.050)

-- -- -0.024 0.013

(0.054)

-- -- -0.032 0.019

(0.048)

-- 0.114

† 0.022 --

(0.067) (0.054)

-- 0.288** 0.105

(0.105) (0.086)

25

Table 3, cont. Unstandardized Coefficients from OLS Regression Models of Self-Rated Health on Employment Type and

Selected Independent Variables.

Model

1

Women

Model

2

Model

3 Model 4

Model

1

Model

2

Men

Model

3 Model 4

0.470*** 0.485***

(0.029) (0.027)

Had Health Shock between

Waves

Constant

(0.051) (0.058)

2.40*** 4.99*** 4.32*** 2.07*** 2.29*** 3.10*** 2.65*** 1.08*

994 994 994 994 787 787 787 787

R

2

0.024 0.079 0.096 0.363 0.013 0.039 0.057 0.297

Note: Coefficients obtained from OLS linear regression models, with standard errors of estimates in parentheses, and significance levels denoted by † p < .10, * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001. Models include an indicator for the number of years in the person-spell (not shown), and are adjusted for repeated observations on the same individual. In the started log transformation of income, a positive constant ($500) is added to each respondent’s annual household income before taking the log; individuals with a score of zero on the measure are therefore retained.

26

Table 4. Unstandardized Coefficients from OLS Regression Models of Depressive Symptoms on Employment Type and

Selected Independent Variables.

Women

Model

Men

Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4

Model

1

Model

3 4

Employment type [Standard omitted]

Prefers Part Time -0.214** -0.208** -0.211** -0.128* 0.041 -0.062 -0.049 -0.010

Part Time, Prefers More 0.223 0.090 0.071 0.034 0.286

† 0.142 0.107 0.117

Self Employed -0.084 -0.061 -0.042 0.026 -0.063 -0.030 0.003 0.019

Black -- 0.298*** 0.261** 0.196** -- 0.231** 0.221** 0.141**

(0.085) (0.081 (0.056)

Childcare hours (in 100s)

(0.064) (0.063) (0.045) (0.072) (0.069) (0.055)

Years of education

(0.003) (0.003) (0.003) (0.004) (0.004) (0.003)

-- -0.059*** -0.058*** -0.040** -- -0.029* -0.029* -0.015

†

Total annual household income

(started log)

(0.015) (0.016) (0.012) (0.012) (0.012) (0.009)

(0.046) (0.047) (0.036) (0.050) (0.052) (0.038)

Blue collar job -- -- 0.089 0.049 -- -- 0.042 0.025

Manufacturing industry

Dissatisfaction with work

(1=low, 5=high)

Not employed at follow-up

(Table continued below.)

--

-- -- 0.061 0.075 -- -- 0.027 -0.016

-- -- 0.063 0.042 -- -- 0.074 0.059

0.074** --

-- 0.062 0.063

(0.075) (0.068)

-- -- 0.309*** 0.190*

(0.086) (0.076)

27

Table 4, cont. Unstandardized Coefficients from OLS Regression Models of Depressive Symptoms on Employment Type and Selected Independent Variables.

Depressive symptoms at baseline

Model

1

Model

2

Women

Model

3 Model 4 Model 1

Men

Model

2

Model

3 Model 4

(0.032) (0.037)

Had Health Shock between

Waves

(0.052) (0.051)

Constant -

0.156** 2.64*** 1.96*** 1.15** 0.257*** 1.88*** 1.17* 0.722

†

2066 2066 2066 2066 1758 1758 1758 1758

993 993 993 993 786 786 786 786

R

2

Note: Coefficients obtained from OLS linear regression models, with standard errors of estimates in parentheses, and significance levels denoted by † p < .10, * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001. Models include an indicator for the number of years in the person-spell (not shown), and are adjusted for repeated observations on the same individual. In the started log transformation of income, a positive constant ($500) is added to each respondent’s annual household income before taking the log; individuals with a score of zero on the measure are therefore retained.

28

Table 5. Unstandardized Coefficients from OLS Regression Models of BMI on Employment Type and Selected

Independent Variables.

Model

1

Employment type [Standard omitted]

Women

Model

2

Prefers Part Time -1.36** -1.14*

Model

3

Model

4

Model

1

Model

2

Men

Model

3

Model

4

(0.467) (0.483) (0.490) (0.147) (0.694) (0.732) (0.755) (0.298)

Part Time, Prefers More 0.023 -0.383 -0.416 -0.144 -0.129 0.016 0.079 -0.684

(0.860) (0.836) (0.842) (0.317) (0.869) (0.861) (0.877) (0.445)

(0.491) (0.506) (0.529) (0.197) (0.473) (0.469) (0.475) (0.122)

(0.015) (0.019) (0.019) (0.006) (0.015) (0.047) (0.018) (0.007)

Black -- † -- 0.252 0.281 0.002

Married -- -0.238 †

Childcare hours (in 100s)

Years of education

Total annual household income

(started log)

Blue collar job

-- -0.089 -0.082 -0.043 -- -0.136 -0.188

† -0.013

Manufacturing industry

Service industry

Dissatisfaction with work

(1=low, 5=high)

Not employed at follow-up

(Table continued below.)

--

--

--

--

--

--

--

--

0.377 -0.024 -- -- -0.588 -0.018

0.105 0.252

0.307 0.171

--

--

--

--

0.299

0.088

0.148

0.061

0.115 *

(0.087) (0.184)

-0.024 0.030

(0.349) (0.182)

-- -- -0.303

(0.431)

-0.062

(0.264)

29

Table 5, cont. Unstandardized Coefficients from OLS Regression Models of BMI on Employment Type and Selected

Independent Variables.

BMI at baseline

Had Health Shock between

Waves

Constant

Model

1

--

Women

Model

2

Model

3

-- --

Model 4

Model

1

0.906***

(0.015)

--

Model

2

Men

Model

3

-- --

Model 4

0.970***

(0.022)

(0.170) (0.133)

25.6*** 34.6*** 33.1*** 0.913 26.6*** 29.7*** 31.3*** 1.54

990 990 990 990 787 787 787 787

R

2

0.045 0.088 0.090 0.769 0.013 0.026 0.029 0.808

Note: Coefficients obtained from OLS linear regression models, with standard errors of estimates in parentheses, and significance levels denoted by † p < .10, * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001. Models include an indicator for the number of years in the person-spell (not shown), and are adjusted for repeated observations on the same individual. In the started log transformation of income, a positive constant ($500) is added to each respondent’s annual household income before taking the log; individuals with a score of zero on the measure are therefore retained.

30

References

Ackers, Peter 2003 The work-life balance from the perspective of policy actors Social Policy and Society

2:3, 221-229.

Allen, T.D., Herst, D.E., Bruck, C.S., & Sutton, M. 2000 Consequences associated with work to family conflict: A review and agenda for future research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 5:

278-308.

Amott, T.,and J. Matthaei. 1991. Race, Gender, and Work: A Multicultural Economic History of Women in the United States . Boston: South End Press.

Baker, David W, Sudano Joseph J, Jeffery M. Albert, Elaine A. Borawski, Avi Dor 2001 “Lack of health insurance and decline in overall health in late middle age”. New England Journal of Medicine . Vol.

345, p 1106-1113

Bardasi, Elena, and Marco Francesconi. 2004. "The Impact of Atypical Employment on Individual

Wellbeing: Evidence from a Panel of British Workers." Social Science and Medicine 58:1671-

1688.

Baumol, W. J., Blinder, A.S., Wolff, E. N. 2003 Downsizing in America: Reality, causes and

consequences . Russell Sage Foundation, New York

Beehr, T.A. 1995. Psychological stress in the workplace . London: Routledge.

Benach, J., M. Amable, C. Muntaner, and F.G. Benavides. 2002. "The Consequences of Flexible Work for

Health: Are We Looking in at the Right Place?" Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health

56:405-406.

Benach, Joan, Fernando G. Benavides, Steven Platt, Ana Diez-Roux, and Carles Muntaner. 2000. "The

Health-Damaging Potential of New Types of Flexible Employment: A Challenge for Public

Health Researchers." American Journal of Public Health 90:1316-1317.

Benach, Joan, David Gimeno, Fernando G. Benavides, Jose Miguel Martinez, and Maria Del Mar Torne.

2004. "Types of Employment and Health in the European Union: Changes from 1995 to 2000."

European Journal of Public Health 14:314-321.

Benavides, F.G., J. Benach, A.V. Diez-Roux, and C. Roman. 2000. "How Do Types of Employment Relate to Health Indicators? Findings from the Second European Survey on Working Conditions."

Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 54:494-501.

Blank, Rebecca M. 1998. "Contingent Work in a Changing Labor Market." Pp. 258-294 in Generating

Jobs: How to Increase Demand for Less-Skilled Workers , edited by R.B. Freeman and P.

Gottschalk. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Bond, T., Galinsky, E. & Swanberg, J.E. 1998 The 1997 national study of the changing workforce . New

York (NK): Families and Work Institute

Brunner, L. and Colarelli, S.M. 2004. Individual Employment Accounts. Independent Review, 8(4),

569 (17).

Cappelli, P., L. Bassi, H. Katz, P. Knoke, P. Osterman, and M. Useem. 1997. Change at Work . New York:

Oxford University Press.

31

Catalano, R., Dooley, D., Novaco, R., Wilson, G., & Hough, R. 1993 a. Using ECA survey data to examine the effect of job layoffs on violent behavior. Hospital and

Community , 44(9), 874-879.

Catalano, R., Dooley, D., Wilson, G., & Hough, R. 1993 b. Job-loss and alcohol abuse: A test using data from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area project. Journal of Health and Social Behavior , 34(3),

215-225.

Chasanov, Amy 2004 Low Wage part-time workers find unemployment insurance elusive.

Economic Policy Institute. www. epinet.org

Christensen, Kathleen. 1990. "Bridges Over Troubled Water: How Older Workers View the Labor

Market." in Bridges to Retirement: Older Workers and a Changing Labor Market , edited by Peter

B. Doeringer. Ithaca, NY: ILR Press.

Cooper, C., 1998 The changing psychological contract at work.

Work and Stress , vol. 12, #2, 97-100

Danziger, S., & Gottschalk, P. 1995. America unequal.

New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Distler, Elaine, Peter Fisher & Colin Gordon 2005 On the fringe: The substandard benefits of workers in part-time, temporary, and contract jobs. Commonwealth Fund publication no. 879. www.cmwf.org.

Dooley, David, and J. Prause. 2004. The Social Costs of Underemployment: Inadequate Employment as

Disguised Unemployment . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Friedland, Daniel S., and Richard H. Price. 2003. "Underemployment: Consequences for the Health and

Well-Being of Workers." American Journal of Community Psychology 32:33-45.

Goldman, Lonnie, and Eileen Appelbaum. 1992. "What Was Driving the 1982-88 Boom in Temporary

Employment: Preference of Workers or Decisions and Power of Employers?" American Journal of

Economics and Sociology 51:473-491.

Geurts, S.A.E. & Demerouti, E. 2003 Work/Nonwork Interface: A review of theories and findings. (In)

M.J. Schabracq, J.A.M. Winnebust, & C.L. Cooper, (Eds.) The Handbook of Work and Health

Psychology . New York: John Wiley &Sons Ltd. pp. 279-312.

Hipple, Steven. 2001. "Contingent Work in the Late 1990s." Monthly Labor Review 124:3-27.

Hochschild, A. 1997 Time bind: When work becomes home and home becomes work.

New

Henry Holt

York:

House, James S., Ronald C. Kessler, A. Regula Herzog, Richard P. Mero, Anne M. Kinney, and Martha J.

Breslow. 1990. "Age, Socioeconomic Status and Health." The Milbank Quarterly 68:383-411

House, James S., James M. Lepkowski, Anne M. Kinney, Richard P. Mero, Ronald C. Kessler, and A.

Regula Herzog. 1994. "The Social Stratification of Aging and Health." Journal of Health and

Social Behavior 35:213-234.

Houseman, Susan N. 2001. "Why Employers Use Flexible Staffing Arrangements: Evidence from an

Establishment Survey." Industrial and Labor Relations Review 55:149-170.

32

Houseman, Susan N. 1999 The policy implications of nonstandard work arrangements. Employment

Research Fall 1999 W. E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research

Hudson, Ken. 1999. "No Shortage of 'Nonstandard' Jobs. Briefing Paper # 89." Washington, D.C.:

Economic Policy Institute.

Institute of Medicine, Coverage Matters: Insurance and Health Care. September 2001, pp 1-8. Committee on the Consequences of Uninsurance

Isaksson, Kerstin S., and Katalin Bellagh. 2002. "Health Problems and Quitting Among Female "Temps"."

European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 11:27-45.

Kalleberg, Arne L. 2000. "Nonstandard Employment Relations: Part-time, Temporary and Contract Work."

Annual Review of Sociology 26:341-365.

Kalleberg, Arne L., Edith Rasell, Naomi Cassirer, Barbara F. Reskin, Ken Hudson, David Webster, Eileen

Applebaum, and Roberta M. Spalter-Roth. 1997. Nonstandard Work, Substandard Jobs: Flexible

Work Arrangments in the U.S.

Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute.

Kalleberg, Arne L., Barbara F. Reskin, and Ken Hudson. 2000. "Bad Jobs in America: Standard and

Nonstandard Employment Relations and Job Quality in the United States." American Sociological

Review 65:256-278.

Karasek, R.A. 1979. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign.

Administrative Science Quarterly , 24, 285-308.

Kasper, Judith D., Terrance A Geovannini, Catherine Hoffman. 2000 “Gaining and losing health insurance: Strengthening the evidence for effects on access to care and health outcomes.”

Medical Care Research and Review Vol 57 No 3 (September 2000) 298-318

Kessler, R., Turner, J., & House, J. 1987. Intervening processes in the relationship unemployment and health. Psychological Medicine , 17, 949-961. between

Kivimaki, Mika, Jussi Vaherta, Marianna Virtanen, Marko Elovainio, Jaana Pentti, and Jane E. Ferrie.

2003. "Temporary Employment and the Risk of Overall and Cause-Specific Mortality." American

Journal of Epidemiology 158:663-668.

Murphy, L.R. in press. Job stress among healthcare workers. In P. Carayon (Ed)

Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics in Healthcare and Patient Safety.

Lawrence Erlbaum, Inc. Publishers

Murphy, L.R. & Sauter, S.L. 2004 Work organization interventions: State of knowledge and future directions Soz Praventive Med , 49: 79-86.

Murphy, L. Sauter, S. Tausig, M. Fenwick, R., Changes in the quality of work life: 1972-2002 Journal of

Occupational and Environmental Medicine (in press

Nollen, S.D. 1996. "Negative Aspects of Temporary Employment." Journal of Labor Research 17:567-581.

Nylen, L., M Voss, and B. Floderus. 2001. "Mortality Among Women and Men Relative to

Unemployment, Part Time Work, and Extra Work: A Study Based on Data from the Swedish

Twin Registry." Occupational and Environmental Medicine 58:52-57.

33

Polivka, Anne E. 1996. "Into Contingent and Alternative Employment: By Choice?" Monthly Labor Review

119:55-74.

Polivka, Anne E., and Thomas Nardone. 1989. "On the Definition of 'Contingent Work'." Monthly Labor

Review 112:9-16.

Price, Richard H. in press The Transformation of Work in America: New Health Vulnerabilities for

American Workers Lawler, Edward . E. and O’Toole, James .[Eds.] The New American

Workplace

Price, R.H., & Kompier, M. In press. Work stress and unemployment: Risks, mechanisms, and prevention. In C.M. Hosman, E. Jane-Llopis, & S. Saxena (Eds.), Prevention of mental disorders: Evidence based programs and policies.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Price, R. H. 1992. Psychosocial impact of job loss on individuals and families. Current Directions in

Psychological Science , 1(1), 9-11.

Price, R. H., Choi, J. N., & Vinokur, A. 2002. Links in the chain of adversity following job loss: How economic hardship and loss of personal control lead to depression, impaired functioning and poor health. Journal of Occupational Health Psycholog y, 7(4), 302-312.

Price, R. H., Friedland, D. S., Choi, J., & Caplan, R. D. 1998. Job loss and work transitions in a time of global economic change. In X. Arriaga, & S. Oskamp (Eds.), problems (pp. 195-222). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Addressing community

Price, R.H., & Kompier, M. In press. Work stress and unemployment: Risks, mechanisms, and prevention. In C.M. Hosman, E. Jane-Llopis, & S. Saxena (Eds.), Prevention of mental disorders:

Evidence based programs and policies . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Quinlan, M., C. Mayhew, and P. Bohle. 2001. "The Global Expansion of Precarious Employment, Work

Disorganization, and Consequences for Occupational Health: A Review of Recent Research."

International Journal of Health Services 31:335-414.

Radloff, Lenore S. 1977. "The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General

Population." Applied Psychological Measurement 1:385-401.

Rifkin, J. 1995 The end of work: The decline of the global labor force at the dawn of the post market era .

G.P. Putnam, New York

Rousseau, D. M., 1995 Psychological contract in organizations: Understanding written and unwritten agreements. Newbury Park, CA: Sage

Schur, Lisa A. 2003. "Barriers or Opportunities? The Causes of Contingent and Part-time Work Among

People with Disabilities." Industrial Relations 42:589-622. People with Disabilities." Industrial

Relations 42:589-622.

Segal, Lewis M., and Daniel G. Sullivan. 1997. "The Growth of Temporary Services Work." Journal of

Economic Perspectives 11:117-36.

Semmer, N.K. 2003. Job stress interventions and organization of work. In J.C. Quick & L.E. Tetrick

(Eds.), Handbook of occupational health psychology (pp. 325-354), Washington, DC: American

Psychological Association.

34

Stratton, Leslie S. 1996. "Are "Involuntary" Part-Time Workers Indeed Involuntary?" Industrial and Labor

Relations Review 49:522-536.

Tausig, M.., Fenwick, R., Sauter, S.L., Murphy, L.R., and Graif, C. 2004. The changing nature of job stress: Risk and resources. In P.L. Perrewe and D. Ganster (eds). Research in

Occupational Stress and Well Being

JAI Press, pp. 93-126

Volume 4. New York:

Taylor, S. E. & Repetti, R. L. 1997 Health psychology: What is an unhealthy environment and how does it get under the skin? Annual Review of Psychology 48: 411-47.

Tilly, Chris. 1996. Half a Job: Bad and Good Part-Time Jobs in a Changing Labor Market . Philadelphia,

PA: Temple University Press.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 1997. "Contingent and Alternative Employment Relationships. USDL

Report 97-422." Washington, D.C.: US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Virtanen, Marianna, M. Kivimaki, Marko Elovainio, J. Vaherta, and J.E. Ferrie. 2003a. "From Insecure to

Secure Employment: Changes in Work, Health, Health Related Behaviours, and Sickness

Absence." Occupational and Environmental Medicine 60:948-953.

Virtanen, Marianna, Mika Kivimaki, Matti Joensuu, Pekka Virtanen, Marko Elovainio, and Jussi Vaherta.

2005a. "Temporary Employment and Health: A Review." International Journal of Epidemiology

34:610-622.

Virtanen, P., V. Liukkonen, J. Vahtera, M. Kivimaki, and M. Koskenvuo. 2003b. "Health Inequalities in the Workforce: The Labour Market Core-Periphery Structure." International Journal of

Epidemiology 32:1015-1021.

Virtanen, P., J. Vaherta, M. Kivimaki, J. Pentti, and J.E. Ferrie. 2002. "Employment Security and Health."

Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 56:569-574.

Virtanen, Pekka, Jussi Vaherta, Mika Kivimaki, Virpi Liukkonen, Marianna Virtanen, and Jane E. Ferrie.

2005b. "Labor Market Trajectories and Health: A Four-Year Follow-up Study of Initially Fixed-

Term Employees." American Journal of Epidemiology 161:840-846.

Walsh, Janet. 1999. "Myths and Counter-Myths: An Analysis of Part-Time Female Employees and Their

Orientations to Work and Working Hours." Work, Employment & Society 13:179-203.

Wenger, Jeffrey B., and Eileen Appelbaum. 2004. "New Jobs, Old Story: Examining the Reasons Older

Workers Accept Contingent and Nonstandard Employment."

Zeytinogku, Isik U., Waheeda Lillevik, M. Bianca Seaton & Josephina Moruz 2004 Part-Time and

Casual Work in Retail Trade: Stress factors affecting the workplace. Relations Industrielles 59, 3

516-543