IDA and Asset-Building Strategies: Lessons and Directions

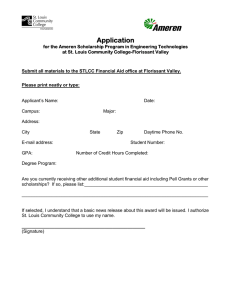

advertisement

IDA and Asset-Building Strategies: Lessons and Directions Michael Sherraden Youngdahl Professor of Social Development Director, Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis, USA Conference on Access, Assets, and Poverty University of Michigan and Brookings Institution October 11-12, 2007 Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Overview of IDA Research: Results to Date, Lessons, Directions On-going body of work on IDAs and inclusive asset building. Asked by the organizers to cover several IDA research methods: non-experimental, cost assessment, experimental. Will attempt to do that, and put the work in context of research directions. This is an opportunity for a mid-course assessment. Your comments, questions, and suggestions are very welcome. Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Motivation: Why Assets? Key to Household Development Basic income and consumption are essential, and in any wealthy and decent society basic income and consumption should be supported. But development of households and families occurs over the long term through asset accumulation and investment -- in education, experience, careers, homes, businesses, and financial instruments. This applies to all families, rich and poor alike. Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Why Assets? Millions in the US Have Little or None About 20% of US households have zero or negative net worth (Mischel et al., 2007). Between 1983 and 2001, the average net worth of the poorest 40% of US household declined by 44%, falling to $2,900 in 2001 (Wolff, 2004). Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Why Assets? Basis of Racial Inequality (Oliver & Shapiro, 2006; Kochhar, 2004; Shapiro, 2004) Ratio of white to non-white income is about 1.5:1 Ratio of white to non-white net worth is about 10.0:1 (Nonwhite here refers to the largest groups of color: Blacks and Hispanics) Asset inequality by race is much greater than income inequality, and has different meaning. If assets are a foundation for household development, then asset inequality may be more fundamental in the long term. Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Increasing Questioning of Income as Sole Definition of Poverty and Well-Being Welfare States have used primarily an income definition of well-being in social policy. Amartya Sen (1993, 1999) and others are looking toward a broader definition of capabilities. Assets can be seen as part of this discussion: one aspect of of long-term capabilities. Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Can Policy Aim for Asset Accumulation? In US, over $300 billion annually in tax expenditures for assets (homes, investments, retirement accounts) Over 90 percent of this goes to households with incomes over $50,000 per year (Sherraden, 1991; Howard, 1997; Seidman, 2001; Corporation for Enterprise Development, 2004) Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis The Poor Do Not Have the Same Opportunities and Subsidies for Asset Accumulation The poor are less likely to own homes, have investments, or have retirement accounts, where most asset-based policies are targeted (Haveman and Wolff, 2005). The poor have little or no tax incentives, or other incentives, for asset accumulation (Seidman, 2001). Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis One Policy Strategy for Asset Building: Individual Development Accounts (IDAs) (Sherraden, 1988, 1991) • Special savings accounts • Started as early as birth • Savings are matched for the poor, up to a cap • Multiple sources of matching deposits • With financial education • For homes, education, business capitalization Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis IDAs in Demonstration Phase IDAs proposed as a universal policy (everyone has an account from birth), with greater subsidies for the poor in the form of matches for deposits. But implemented as short-term (3 to 5 year) demonstrations targeting low-income households, in community-based projects. Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Research on IDAs: American Dream Demonstration (ADD) • • • • • • • First major demonstration of IDAs Fourteen IDA programs around the country ADD from 1997 through 2001, research through 2005 Organized by Corporation for Enterprise Development Research plan by Center for Social Development Experiment designed and led by Abt Associates Funded by twelve foundations (Ford has been the major supporter, with partnerships from CS Mott, Citigroup, Fannie Mae, EM Kauffman, MetLife, FB Heron, Levi Strauss, Rockefeller, and others) Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis ADD Research Agenda: Multiple Methods Research methods in ADD have been multiple, each making unique contributions. In this presentation, we look at four research methods: • • • • Account monitoring research In-depth interviews Cost assessment Experiment Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Account Monitoring Research Data set from MIS IDA, created by CSD for this purpose. Record of all savings transactions for all participants. Very accurate data on saving, coming from bank records. Perhaps the most thorough existing data set on saving in low-income households. Analysis using two-step regression. First identifies factors associated with being a “saver” (net savings of over $100), then among “savers”, identifies factors associated with average monthly net deposit (Schreiner & Sherraden, 2007). Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Account Monitoring: Limitations and Usefulness All participants in ADD are self-selected and program selected. This data set from all 14 ADD sites does not have a counterfactual, and cannot address impacts. This data set can address IDA savings patterns and outcomes, as well as participant and program characteristics associated with IDA savings, controlling for many other variables. Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Account Monitoring Research: Overall Savings Outcomes (Schreiner & Sherraden, 2007) Number of IDA participants in ADD = 2,364 Average monthly net deposit (AMND) = $16.60 About half of IDA participants (52%) were “savers” “Savers” had AMND of $32.44 Match rates varied, with 2:1 most typical Of every $1.00 that could be matched, $0.42 was saved. Home purchase is the most popular use of IDAs (with positive impact in experimental conditions). Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Uses of IDA Savings in ADD: Matched Withdrawals Of matched withdrawals taken by the end of ADD: 26% for microenterprise 22% for home repair 21% for home purchase 21% for post-secondary education 7% for retirement 2% for job training Home purchase and repair continue to be popular (48%). When offered (to 35% of participants) retirement saving is also a popular option. Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Account Monitoring Research: Individual Variables Controlling for many other factors, income (both recurrent and intermittent) is weakly associated with savings outcomes. The poorest ADD participants saved a higher proportion of their income in IDAs Employment and welfare receipt (past or current) was not associated with saving outcomes in IDAs. These results suggest that something other than the observed individual characteristics may be leading to savings outcomes in IDAs. Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Account Monitoring Research: Program Variables We look briefly at: Match rate Match cap Direct deposit Financial education Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Match Rate Matching seems to attract and hold participants in IDAs. Controlling for many participant and program variables, higher match rates are associated with the probability of being a “saver”. But among “savers”, higher match rates are associated with lower AMND. It could be that a higher match substitutes for an individual’s own saving to reach a saving goal. Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Match “Cap” Controlling for many other factors, the amount that can be matched (“match cap”) is strongly associated with net monthly savings. Each additional dollar of match cap is related to an additional $0.57 in net monthly savings (a large effect). Participants appear to turn the match cap into a savings target. Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Automatic Deposit Controlling for many other factors, automatic monthly deposit is associated with participants being “savers” But among “savers”, direct deposit has no statistical relationship with AMND. This may be due to saving being on “autopilot” with direct deposit. Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Financial Education Among “savers” the first 10 hours of financial education is positively associated with AMND, with no relationship after 10 hours. This is important, because financial education is quite expensive to deliver, and perhaps the full benefit is in the first 10 hours. Each of the first 10 hours is associated with an increase of $1.16 in AMND. Therefore 10 hours is associated with an increase of $11.60 per month or $139 per year, which would be $418 if matched 2:1, and $1,670 over four years. Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Summary Observations from Account Monitoring Research Overall, it may be that program characteristics are as or more important than individual characteristics in explaining savings outcomes in IDAs. Regarding program characteristics, more than incentives (in the form of matches) are related to savings outcomes. The positive effect of incentives may be in attracting and keeping people saving in the program, and not in saving amount by those who participate (see also Engen, Gale, & Scholz, 1996). Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Beyond Program Characteristics: Institutional Constructs that May Affect Saving and Asset Accumulation • • • • • • • • Access (eligible, available, default enrollment) Information (financial education, feedback) Incentives (match rates, other inducements) Facilitation (direct deposit, personal assistance) Expectations (match cap, saving targets) Restrictions (pre-commitment, restricted uses) Security (money safe, dependable access) Simplicity (simple products, limited choices) Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Toward Policy: An Inclusive Savings Plan Policy implications are for a saving plan with desirable institutional features, similar to a 401(k) Plan, Federal Thrift Savings Plan, or 529 College Savings Plan. Desirable features might include: automatic enrollment, low initial deposits, simple investment options, low annual fees, financial education, matched savings for the poor, and target savings amounts (Clancy et al., 2003, 2004, 2005). As particular application, “Save More Tomorrow” illustrates potential of a plan structure (Thaler & Benartzi, 2003). Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Insights from In-depth Interviews (Margaret Sherraden et al., 2005; Margaret Sherraden & Mcbride, forthcoming) Subsample of ADD experiment, 60 IDAs and 30 controls One key finding: IDA funds are not perfectly fungible. Participants have mental understanding of short-term and long-term accounts and value this distinction, e.g., glad that IDA savings are “out of reach”. Another key finding: IDA participants understand the matchcap as a target saving amount. The institutional construct of “expectations” emerged from in-depth interviews. Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis IDAs and Future Orientation IDA participants say they can “see more clearly” and better “visualize a future” than before IDAs. IDA program is said to “create goals and purpose.” IDA program is said to provide “way to reach goals.” With these changes in outlook and capability, IDA participants say they are “more able to save”, “look forward to saving”, and “plan to save for the future”. These findings from in-depth interviews may support a cognitive approach to understanding the influence of institutions on savings outcomes. Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis How Much Do IDAs Cost? (Schreiner 2002, 2006) Thorough cost assessments published by CSD. Has caused our policy colleagues some challenges, but necessary. Program costs for administration (not counting matching funds) are about $61 per month. In part, high costs are due to demonstration (e.g., start-up inefficiency, communications, policy involvement), but IDAs are unlikely in this community-based model to get much below $30 per month. Compare to 401(k) administration of about $10 per month, and intensive family intervention that may reach $400 per month. Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Demonstration Model: Cost Is a Barrier to Scale We do not yet know if IDAs are cost beneficial. ADD Wave 4 will include a cost-benefit analysis. All things considered, it seems unlikely that monetizable benefits in ADD will exceed costs. Even if the cost-benefit outcome is positive (possible), high administrative costs will be a barrier to large-scale policy expansion. The most scalable form of IDAs or other progressive savings will be a large, centralized, efficient plan structure (discussed above). Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis The ADD Experiment: What Are the Measured Impacts? (Mills et al., 2004, 2006, forthcoming) Experiment in Tulsa, OK, with 1103 participants randomly assigned to treatment and control groups, three waves, 1998 to 2002. ADD implemented by CFED, IDA program run by CAPTC, with Abt Associates leading the experiment. CSD provided Coordination. Abt was funded directly and did not report to CSD. CSD asked to step back so that Abt can report the basic experimental results, which we have been glad to do. Key financial impacts are reviewed in this paper. Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Impact on Homeownership Mills et al. (2004): For treatment group, + 6.2 percentage points Mills et al. (2006): For black renters, +10% percentage points Mills et al. (forthcoming): For renters, +7 to 11% percentage points Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Interpreting Home Ownership Impact It seems likely that research results in home ownership, which is dichotomous, may have less measurement error than financial variables, as these stable results may indicate. A 6 to 11% positive impact in home ownership is large, and could be a very positive outcome in ADD, especially if more African Americans have become homeowners. But perhaps IDAs only rushed people into homeownership who would have done so otherwise. Or perhaps IDAs encouraged home ownership among people who cannot sustain it over the long term. All of this remains to be seen. Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Impact on Net Worth Mills et al. (2004): +$29 (NS) Mills et al. (2006): +$2,118 (NS) Mills et al. (forthcoming): +$1,339 (NS) Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Interpreting Net Worth Impact The most apparent explanation is that there is no increase in net worth due to IDAs during this period. It could be that closing costs are not yet recovered in home equity growth. In other words, home ownership may take longer to show up as a change in net worth (Mills et al., all three versions). It could be that extreme values in ADD data, leading to large standard errors, make it impossible to identify a modest underlying impact on net worth if it existed. One analysis by Abt, addressing extreme values by trimming 3% of net worth values and setting out-of-range controls to the mean, finds a positive impact on net worth ($5,390, p<.01). Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Interpreting New Worth Impact (cont.) Overall, Bill Gale’s assessment is that it is not possible to say with this data set whether net worth increased on not due to large variance in changes in net worth and relatively small sample size (Mills et al., forthcoming). The analysis by Abt cited above may suggest that variance is a greater challenge than sample size, including variance in both net worth and controls. CSD will offer additional analyses that attempt to deal with extreme values and possible measurement error (APPAM in November). Regardless of these findings, we agree that conclusions on net worth may be unwarranted at this time. Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Selected Impacts: Other Assets & Liabilities Mills et al. (2004), for all IDA group: Real assets +$6,310 (p<.10) (+ p<.05 for black and 36+) Total assets +$4,186 (NS) (+ p<.10 for black and 36+) Total liabilities +4,157 (NS) (+p<.10 for black and 36+) Mills et al. (2006): For all IDA group, +computer purchase (p<.05) For black renters, +$4,073 home equity (p<.05) For black renters, -$1,348 financial assets (p<.10) For black renters, -business ownership (p<.10) For white renters, +$1,747 business equity (p<.05) Mills et al. (forthcoming): For all IDA group, financial assets -$1,925 (p<.05) Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Interpreting Asset & Liability Impacts Overall, some indication that both assets and financial liabilities increased. It could be that increased asset ownership, even if offset by liabilities, represents a positive (or negative) impact. Having greater assets and greater liabilities could represent a higher level of economic functioning with greater well being, as may occur in owning a home with mortgage debt. Or conversely, taking on greater liabilities to purchase assets could lead to debt problems that limit future well being. Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Next Step: ADD Experiment, Wave 4 As indicated above, many questions remain unanswered. In key respects, the time period for 3 waves of ADD was short, and a follow-up Wave 4 may be informative. ADD Experiment Wave 4 is now in planning and should be in the field in 2008. Supported by the MacArthur and F.B. Heron Foundations (so far). The research team is led by University of North Carolina, with Brookings Institution and CSD as partners, and survey data collection by RTI International. Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Influence of IDA Research in US IDAs included as a state option in 1996 “welfare reform” Act (Boshara, 2003) Federal Assets for Independence Act in 1998, first public IDA demonstration (Boshara, 2003). Over 40 US states now have some type of IDA policy (Edwards & Mason, 2003; Warren & Edwards, 2005) United Way of American in 2007 announced a $1.5 billion Financial Stability Partnership focused on increasing income, savings, IDAs, and protecting assets. Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Influence of ADD Research Internationally Saving Gateway and Child Trust Fund in the United Kingdom (Kelly and Lissauer, 2000; Blair, 2001; Sherraden, 2002, H.M. Treasury, 2003; Paxton, 2003; Kempson et al., 2003, 2006) Family Development Accounts by Taipei City (Cheng, 2003) IDAs and “Learn$ave” demonstration in Canada (Kingwell et al., 2003) Matched saving in Australia (ANZ Bank), Uganda (CSD’s AssetsAfrica initiative), Colombia and Peru (International Fund for Agricultural Development), Hungary (OSI). Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Example: Matched Savings with HIV/AIDS Orphans in Uganda (Ssewamala and Curley, 2005) High risk population, including likely HIV infection later Aiming for US$600 for secondary schooling Savings of $200 matched with $400 Pilot successful Now larger project with NIH funding: • One of few NIH grants outside of US • One of first NIH grants to test economic intervention on health outcomes (preventing HIV infection as children grow older) So far, evidence of positive impact (vs. comparison group) on HIV prevention attitudes and educational planning (Ssewamala et al., 2007). Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Children’s Development Accounts: Potential in the United States Average children’s allowance in Western Europe is 1.8% of GDP. US has no children’s allowance and under-invests in children. Even 0.1% of US GDP would be enough for a $2,500 start in life account for every newborn (Curley & Sherraden, 2000). Many proposals now in the US Congress for CDAs (New America Foundation, 2004, 2006). Recently Sen. Clinton proposed an account for every US Newborn, with initial $5,000 deposit. Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Next Step: Testing CDAs in the US: The SEED Demonstration Twelve SEED demonstration sites around the country, multiple research methods. Partners are CFED, New America Foundation, University of Kansas, Research Triangle Institute, Aspen Institute, and CSD. Research funding for SEED from Ford, CS Mott, MetLife, Lumina, and Smith Richardson (pending) foundations. CSD is organizing an experiment (random assignment at birth) in one state (Oklahoma), using the 529 College Savings Plan: 1,490 participants and 1,490 controls, $1,000 deposits at birth and matching savings, seven-year project to 2014. Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis Last Comment: Payoffs of Demonstration Research Field demonstrations over an extended period can be challenging to implement and carry out. They depend on cooperation among many different partners. But payoffs of demonstration research include: • • • • • Provides opportunity to test and improve an innovation Builds practitioner and field capacity Creates examples that can influence policy Yields research that can inform knowledge and policy Trains new scholars for future research and analysis Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis References Beverly, S.G., & Sherraden, M. (1999). Institutional determinants of saving: Implications for low-income households and public policy, Journal of Socioeconomics 28, 457-473. Blair, T. (2001). Savings and assets for all, speech. London: 10 Downing Street, April 26. Boshara, R. (2003). Federal policy and asset building. Social Development Issues 25(1&2), 130-141. Bynner, J.B., & Paxton, W. (2001). The asset effect. London: Institute for Public Policy Research. Caner, A., & Wolff, E.N. (2004). Asset poverty in the United States. Levy Economics Institute, Bard College. Cheng, Li-Chen (2003). Developing Family Development Accounts in Taipei: Policy innovation from income to assets. Social Development Issues 25(1/2), 106-117. Clancy, M., Cramer, R., & Parrish, L. (2005). Section 529 savings plans, access to post-secondary education, and universal asset building. Washington: New American Foundation. Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis References (cont.) Clancy, M, Orszag, P., & Sherraden, M. (2004). College savings plans: A platform for inclusive savings policy? St. Louis: Center for Social Development, Washington University. Clancy, M., & Sherraden, M. (2003). The potential for inclusion in 529 savings plans: Report of a survey of states. St. Louis: Center for Social Development, Washington University in St. Louis. Corporation for Enterprise Development (2004). Hidden in plain site: A look at the $335 billion federal asset-building budget. Washington: Corporation for Enterprise Development. Curley, J., & Sherraden, M. (2000). Policy lessons from children’s allowances for children’s savings accounts, Child Welfare, 79(6), 661-687. Edwards, K., & Mason, L.M. (2003). State policy trends for Individual Development Accounts in the United States, Social Development Issues 25 (1&2), 118-129. Engen, E.M, Gale, W., & Scholz, J. (1996). The illusory effects of savings incentives on saving, Journal of Economic Perspectives 10(4), 113-138. Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis References (cont.) Goldberg, F. (2005). The universal piggy bank: Designing and implementing a system of savings accounts for children. In M. Sherraden, ed., Inclusion in the American dream: Assets, poverty, and public policy. New York: Oxford University Press. H.M. Treasury (2003). Details of the Child Trust Fund. London: H.M. Treasury. Haveman, R., & Wolff, E.M. (2005). Who are the asset poor? Levels, trends, and composition, 1983-1998. In M. Sherraden, ed., Inclusion in the American dream: Assets, poverty, and public policy. New York: Oxford University Press. Howard, C. (1997). The hidden welfare state: Tax expenditures and social policy in the United States. Princeton: Princeton University Press Kempson, E., McKay, S., & Collard, S. (2003). Evaluation of the CFIL and Saving Gateway pilot projects. Bristol, United Kingdom: University of Bristol. Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis References (cont.) Kempson E, Atkinson A, Collard S (2006). Saving for children: A baseline survey at the inception of the Child Trust Fund, HM Revenue & Customs Research Report 18. Personal Finance Research Centre, University of Bristol. Kingwell, P., Dowie, M., Holler, B., & Jimenez, L. (2004). Helping people help themselves: An early look at Learn$ave. Ottawa, Canada: Social Research and Demonstration Corporation. Kelly, G., & Lissauer (2000). Ownership for all. London: Institute for Public Policy Research. Kochhar, R. (2004). The wealth of Hispanic households. Washington: Pew Hispanic Center. Lindsey, D. (1994). The welfare of children. New York: Oxford University Press. Loke, V., & Sherraden, M. (2006) Building assets from birth: Comparison of policies and proposals on Children’s Savings Accounts, working paper. St. Louis: Center for Social Development. Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis References (cont.) Midgley, J. (1999). Growth, redistribution, and welfare: Toward social investment, Social Service Review 77(1), 3-21. Mills, G., Patterson, R., Orr, L., & Demarco, D. (2004). Evaluation of the American Dream Demonstration, final report. Cambridge, MA: Abt Associates. Mills, G., Gale, W.G., Patterson, R., & Apostolov, E. (2006). What do individual development accounts do? Evidence from a controlled experiment, working paper. Washington: Brookings Institution. Mills, G., Gale, W.G., Patterson, R., Englehardt, G.V., Eriksen, M.D., & Apostolov, E. (forthcoming). Effects of Individual Development Accounts on asset purchases and saving behavior: Evidence from a controlled experiment. Mishel, L., Berstein, J., Allegretto, S. (2007). The state of working America. Washington: Economic Policy Institute. Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis References (cont.) New America Foundation (2004). ASPIRE Act summary. Washington: New America Foundation. New America Foundation (2006). Savings accounts for kids: Current federal proposals. Washington: New America Foundation. Nissan, D., & LeGrand, J. (2000). A capital idea: Start-up grants for young people, policy report no. 49. London: Fabian Society. Oliver, M., & Shapiro, T. (2006). Black wealth/white wealth, second edition. New York: Routledge. Paxton, W., ed. (2003). Equal shares? Building a progressive and coherent asset-based welfare policy. London: Institute for Public Policy Research. Russell, R., & Fredline, L. (2004). Evaluation of the Saver Plus pilot project. Australia: RMIT University. Schreiner, M. (2006). Program costs for Individual Development Accounts: Final figures from CAPTC in Tulsa, Savings and Development 30(3), 247274. Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis References (cont.) Schreiner, M., & Sherraden, M. (2007). Can the poor save? Savings and asset building in Individual Development Accounts. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction. Seidman, L. (2001). Assets and the tax code. In T. Shapiro & E.N. Wolff, eds., Assets for the poor: Benefits and mechanisms of spreading asset ownership, 324-356. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. Sen, A. (1993). Capability and well-being. In M. Nussbaum & A. Sen, eds., The quality of life, 30-53. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. New York: Knopf. Shapiro, T. (2004). The hidden costs of being African-American. New York: Oxford University Press. Sherraden, M.S., & McBride, A.M. (forthcoming). Particicipant views of IDAs (working title). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Sherraden, M.S., McBride, A.M, Hanson, S., & Johnson, L. (2005). The meaning of saving in low-income households, Journal of Income Distribution 13(3-4). Sherraden, M. (1988). Rethinking social welfare: Toward assets. Social Policy 18(3), 37-43. Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis References (cont.) Sherraden, M. (1991). Assets and the poor. Armonk, NY: ME Sharpe. Sherraden, M. (2002). Opportunity and assets: The role of the Child Trust Fund, seminar organized by Prime Minister Tony Blair, 10 Downing, and dinner speech with Chancellor of the Exchequer Gordon Brown, 11 Downing, London, September 19. Sherraden, M., & Barr, M.S. (2005). Institutions and inclusion in saving policy, in N. Retsinas & Eric Belsky, eds., Building assets, building credit: Creating wealth in low-income communities. Washington: Brookings Institution. Sherraden, M., Schreiner, M., & Beverly, S. (2003). Income, institutions, and saving performance in Individual Development Accounts, Economic Development Quarterly 17(1), 95-112. Sswamala, F., Alicea, S, Bannon, W.M, & Ismayilova, L. (2007). A novel economi intervention to reduce HIV risks among school-going AIDS orphans in rural Uganda, Journal of Adolescent Health. Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis References (cont.) Ssewamala, F.S., & Curley, J. (2005). Improving life chances of orphan children in Uganda: Testing an asset-based development strategy, working paper 05-01. St. Louis: Center for Social Development. Thaler, R., & Benzartzi, S. (2004). Save More Tomorrow: Using behavioral economics to increase employee saving, Journal of Political Economy 112, S164-S187. Warren, N., & Edwards, K. (2005). Status of State Supported IDA Programs in 2005, working paper 05-03. St. Louis, Center for Social Development. Williams Shanks, T.R. (2007). The impacts of household wealth on child development, Journal of Poverty 11(2), 93-116. Wolff, E.N. (2004). Changes in household wealth in the 1980s and 1990s in the United States, working paper no. 407. Levy Economics Institute, Bard College. Zhan, M., & Sherraden, M. (2003). Assets, expectations, and children’s educational achievement in single-parent households, Social Service Review 77(2), 191-211. Center for Social Development Washington University in St. Louis