Redesigning Distribution:

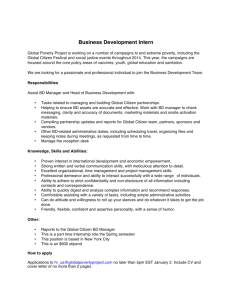

advertisement