CIFE

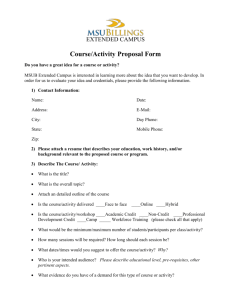

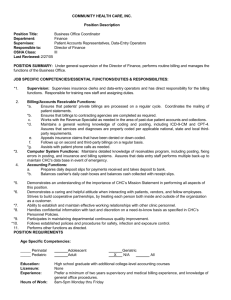

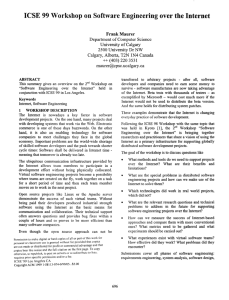

advertisement