Lottery Expenditures in Canada: Regional Analysis of Probability of Purchase,

advertisement

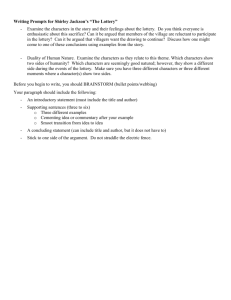

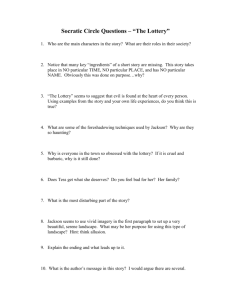

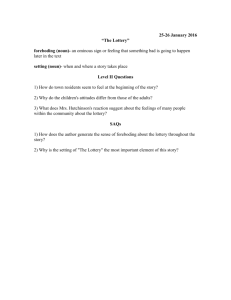

FAMILY AND Sharpe Abdel-Ghany, CONSUMER / LOTTERY SCIENCES EXPENDITURES RESEARCHIN JOURNAL CANADA Lottery Expenditures in Canada: Regional Analysis of Probability of Purchase, Amount of Purchase, and Incidence Mohamed Abdel-Ghany University of Alabama Deanna L. Sharpe University of Missouri This article has two purposes: First, to examine the effect of household characteristics on lottery expenditures in six regions of Canada using a double hurdle model to distinguish between the decision to play and the decision of how much to spend. Second, to estimate the incidence of lottery expenditures. Using the 1996 Canadian Family Expenditure Survey, the results portray the profile of households that have the probability of becoming participants in lottery play as well as the profile of households that spend more on lottery purchases. Lottery expenditures are found to be regressive in all regions. In the past three decades since lotteries were introduced in Canada, they have grown into a multibillion-dollar industry. During fiscal year 2000, Canadian lottery sales reached $9.1 billion (Canadian dollars). Per capita sales was $291 in Canada. Quebec led the provinces with fiscal sales of $3.4 billion, followed by Ontario ($2.2 billion). On a per capita basis, the Canadian leader in lottery sales was the Lotto-Quebec lottery ($465) (North American Association of State and Provincial Lotteries [NASPL], 2000a). In Canada, lotteries are overseen by provincial governments and are marketed and distributed collaboratively by a cartel of provincial agencies. In the Maritimes, for example, lotteries are managed and conducted under the auspices of the Atlantic Canada Lottery Corporation that was established in 1976, comprising representation from each of the four Maritime Provinces. The Western Canada Lottery Corporation operates in a similar fashion by coordinating the efforts of Alberta, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Northwest Territories, Nunavut, and Yukon Territory and was established in 1974. Ontario, Quebec, and British Columbia each operate their own lottery entities, Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, Vol. 30, No. 1, September 2001 64-78 © 2001 American Association of Family and Consumer Sciences 64 Abdel-Ghany, Sharpe / LOTTERY EXPENDITURES IN CANADA 65 which were established in 1975, 1969, and 1985, respectively. All provinces combine at the national level for Canada-wide lotteries through the jointly owned Inter-Provincial Lottery Corporation (NASPL, 2000b). Canadian jurisdictions promote gambling as an economic development tool that creates jobs, funds charitable groups, and augments provincial coffers. Lottery proceeds benefit different programs in different jurisdictions. In many cases, lottery profits are combined with tax and other revenues in a government’s general fund. In other cases, lottery proceeds are set aside for a specific cause, such as education, cultural activities, economic development, environmental programs, health care, sports facilities, tax relief, programs for the elderly, and others. One image of the legal lottery industry sometimes advanced by its critics is that it preys on ignorance or, at best, the false hopes of those who live at the lower end of the Canadian economic spectrum. Despite the deep-seated moral and ethical arguments that may be put forward by local groups and individuals, it is most helpful to move the debate to the level of factual information. Most important is the extent to which various socioeconomic and demographic variables are instrumental in determining the probability of lottery purchase as well as the amount of purchase. One public policy issue stemming from the lottery is tax regressivity (lottery expenditures as a percentage of income fall as income increases), and related to this is the fear that some households, especially the poor, overspend on lottery purchases and become impoverished due to states’ promotion of gambling. The purpose of this study is twofold: (a) to examine the effects of a number of socioeconomic and demographic variables on the probability of lottery purchase as well as the amount of purchase in the six regions of Canada, and (b) to determine the extent to which lottery purchases are regressive in their incidence on taxpayers. REVIEW OF LITERATURE Most previous studies have focused on determining the economic burden of the implicit lottery tax (Borg & Mason, 1988; Brinner & Clotfelter, 1975; Clotfelter, 1979; Clotfelter & Cook, 1987, 1989; Hansen, 1995; Hansen, Miyazaki, & Sprott, 2000; Heavey, 1978; Mikesell, 1989; Spiro, 1974; Suits, 1977). With the exception of the 66 FAMILY AND CONSUMER SCIENCES RESEARCH JOURNAL Clotfelter and Cook (1989) and Mikesell (1989) studies, previous literature shows that people in lower income categories spend a greater percentage of their income on lottery tickets and thus on the tax inherent in the price of tickets. Livernois (1987) examined both the tax and the expenditure incidence of lottery profits in western Canada. He concluded that the lottery redistributes income from low-income to high-income groups. Another area of lottery research addresses the question of who is more likely to participate in playing the lottery and to what extent. Province lottery agencies are very interested in this issue, as this information allows them to target these groups with lottery advertising and lottery retail outlets. The studies by Clotfelter and Cook (1989), Mikesell (1989), and Hansen (1995) provide a detailed examination of the socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of lottery players that significantly determine lottery ticket purchases in the United States. These studies indicate that minority groups are more likely to play than nonminority groups. They also find that lottery sales are inversely related to educational levels, suggesting that less educated individuals have higher lottery ticket expenditures relative to those more educated individuals. Place of residence is also found to be a significant determinant of lottery ticket expenditures. Also, individuals living in urban areas tend to have higher lottery expenditures relative to individuals living in rural areas. Kitchen and Powells (1991) examined the determinants of household lottery expenditures in the six regions of Canada using micro data. They concluded that some household characteristics such as wealth, age, occupation, mother tongue, and urban location vary in the extent to which they significantly affect the level of lottery expenditures across regions. Other household characteristics such as after-tax household income, gender, and education of the head have the same effect on lottery expenditures regardless of the region. They also concluded that in spite of the fact that the Canadian lottery expenditures are found to be regressive, they are less regressive in their impact than American lotteries. Kitchen and Powells (1991) used the Tobit estimation technique to obtain the parameter estimates. This technique accounts for the influence of the explanatory variables on the probability of whether to buy lottery tickets as well as their effect on the decision regarding the amount to purchase once the choice to buy has been made. Although the decisions of whether to purchase lottery tickets versus how much Abdel-Ghany, Sharpe / LOTTERY EXPENDITURES IN CANADA 67 to spend by those choosing to purchase may be influenced by many of the same socioeconomic and demographic factors, there is no reason to believe that an explanatory factor common to both decisions must have the same sign and magnitude in both decisions. Scott and Garen (1994), using a selection-bias-corrected ordinary least squares regression method investigated individual lottery ticket purchases in the state of Kentucky. They also estimated the lottery ticket demand function by a consistent two-step procedure and developed a Chow test to determine if the Tobit restrictions were appropriate. They concluded that the use of Tobit statistical procedure in analyzing lottery purchases lead to mis-specification of the model due to the situation of discontinuous consumer’s indifference curves resulting perhaps from stigma and/or fixed cost of purchase. Stranahan and Borg (1998) analyzed Scott and Garen’s model and showed that the truncated Tobit and probit is a better methodology for estimating lottery expenditures. Using data from telephone interview surveys in Florida, Virginia, and Colorado, their results showed that age, race, education, and other variables have very different effects on the probability of play versus the amount spent on lottery products. This study improves on previous research in several ways. First, the Canadian expenditure data used in this study are recent. Second, these are the only expenditure data that allow an analysis of lottery expenditures. Third, this study uses a statistical method that offers advantages over the Tobit analysis used in previous research (Cragg, 1971). DATA AND METHOD Data for this proposed study are derived from the 1996 Canadian Family Expenditure Survey. The Family Expenditures Surveys Section, Household Surveys Division, Statistics Canada released the data set to public use in May 1999. This survey of households was designed to yield a representative sample of persons in private households in 17 metropolitan areas of Canada. The data set excludes persons living on Indian reservations, patients in old age homes and hospitals, persons in penal institutions, and families of official representatives of foreign countries. Our sample from this set of data consisted of 10,079 households. All expenditure and income quantities are annualized (Statistics Canada, 1996, p. 6). 68 FAMILY AND CONSUMER SCIENCES RESEARCH JOURNAL Analysis of lottery expenditures presents a challenge. Not everyone would choose to participate in a lottery. A large number of zero expenditures makes ordinary least squares analysis inappropriate (Greene, 1993). Although Tobit analysis can account for a large number of zeros, it presumes the sign and significance of the factors affecting the decision to participate and the decision of how much to participate are the same. This presumption is not likely to be correct for lottery expenditures. So-called double hurdle models are now established in the literature as being superior to Tobit modeling in dealing with the problem of a large number of zero expenditures (Cragg, 1971). Unlike the Tobit model, the double hurdle model explicitly recognizes that the factors associated with the decision to participate may have a different influence on the level of participation among those who choose to participate. In consumption studies, double hurdle models can be used to separate the decision to consume (participate) from the level of consumption (expenditures) and, therefore, provide more meaningful insights into consumers’ behavior than does the Tobit model (Cragg, 1971). Moreover, although many of the same factors (such as income and demographics) may influence both participation and expenditure, they may have different effects on participation. The double hurdle model specifies a participation equation, Xα + µ, and an expenditure (consumption) equation, Yβ + ε, such that expenditures, E, are modeled as, E = Yβ + ε, if Xα + µ > 0 and Yβ + ε > 0; = 0 otherwise, where X and Y are vectors of explanatory variables, α and β are vectors of parameters, and µ and ε are the error terms. As measured in the Canadian Family Expenditures Survey, “participation” in lottery play is a “yes-no” proposition; the dependent variable of the participation equation is a one-zero indicator. Following standard practice supported by the literature, we estimate this equation using probit methods rather than by logit or dependent variable techniques. As expenditures on lottery are continuous above zero, the consumption equation is estimated using truncated regression analysis (Cragg, 1971; Greene, 1993). LIMDEP version 7 (Greene, 1995) was used to estimate the equations in this study. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION Variable descriptions are given in Table 1. Table 2 lists the independent variables used to specify the participation and expenditure Abdel-Ghany, Sharpe / LOTTERY EXPENDITURES IN CANADA 69 TABLE 1: Variable Definitions Used to Examine Effect of Household Characteristics on Lottery Expenditures in Canada and Incidence of Lottery Expenditures Variable Definition EX HI HW Age Urban Average dollar expenditures per year on lottery Household income after tax in $10,000 Household wealth (net value of dwelling in $10,000) Age in years of reference person 1 if household lives in urban area; 0 otherwise Education ED1 ED2 ED3 1 if high school; 0 otherwise 1 if some college; 0 otherwise 1 if college degree; 0 otherwise Country of birth CB1 1 if Canada; 0 otherwise Occupation OC1 OC2 OC3 OC4 OC5 OC6 1 if managerial/professional and technical; 0 otherwise 1 if teaching; 0 otherwise 1 if sales/service/clerical; 0 otherwise 1 if blue collar; 0 otherwise 1 if other; 0 otherwise 1 if not stated; 0 otherwise Type of household TY1 TY2 TY3 TY4 1 if one-person; 0 otherwise 1 if married; 0 otherwise 1 if lone-parent; 0 otherwise 1 if other; 0 otherwise Presence of children younger than 15 years of age CH15 1 if present; 0 otherwise equations. For each variable, we show the sample average computed over the full sample and over the subset of lottery players in each of the six regions of Canada. Units of measurement are also given in the table. Our choice of explanatory variables was predicated on demand theory and was consistent with many previous studies related to this topic (e.g., Kitchen & Powells, 1991; Stranahan & Borg, 1998). The age, education, country of birth, and occupation indicators in this sample of households refer to attributes of the household reference person, the household member primarily responsible for the financial maintenance of the household. All other variables listed, such as after-tax income, wealth, residence, type of household, and 70 TABLE 2: Variable Definitions and Mean Statistics in Examining Effect of Household Characteristics on Lottery Expenditures in Canada and Incidence of Lottery Expenditures Atlantic Canada Entire Sample n= 2,350 EX HI HW Age Urban Lottery Players n= 1,854 Quebec Entire Sample n= 1,545 British Columbia Lottery Players n= 1,331 Entire Sample n= 1,448 Lottery Players n= 1,157 244.11 309.42 243.93 283.15 226.83 283.88 3,541 3,762 3,435 3,525 4,045 4,206 4,462 4,605 4,195 4,274 11,250 11,390 47.4 47.8 47.8 47.7 48.2 47.9 0.72 0.730 0.89 0.89 0.93 0.93 Ontario Entire Sample n= 2,396 Manitoba/ Saskatchewan Alberta Lottery Players n= 1,876 Entire Sample n= 821 Lottery Players n= 679 Entire Sample n= 1,519 Lottery Players n= 1,238 260.56 332.78 300.07 362.82 270.97 332.47 4,333 4,595 4,362 4,494 3,656 3,866 8,179 8,339 6,598 6,452 4,499 6,633 48.4 47.6 45.9 44.6 48.7 48.1 0.93 0.93 0.90 0.90 0.85 0.85 Education ED1 ED2 ED3 CB1 0.43 0.28 0.13 0.94 0.43 0.30 0.13 0.95 0.40 0.29 0.12 0.89 0.41 0.29 0.11 0.90 0.38 0.37 0.18 0.70 0.38 0.38 0.16 0.72 0.40 0.29 0.18 0.69 0.41 0.30 0.17 0.71 0.39 0.35 0.17 0.78 0.41 0.37 0.15 0.80 0.44 0.27 0.14 0.86 0.45 0.28 0.14 0.88 Occupation OC1 OC2 OC3 OC4 OC5 OC6 0.16 0.03 0.16 0.19 0.08 0.02 0.17 0.03 0.18 0.20 0.08 0.01 0.18 0.03 0.19 0.17 0.09 0.01 0.18 0.03 0.18 0.20 0.09 0.01 0.20 0.03 0.18 0.17 0.06 0.04 0.21 0.03 0.19 0.18 0.06 0.04 0.21 0.03 0.17 0.17 0.09 0.02 0.21 0.03 0.18 0.20 0.10 0.14 0.23 0.03 0.21 0.22 0.07 0.03 0.23 0.04 0.22 0.23 0.07 0.03 0.20 0.03 0.17 0.18 0.08 0.03 0.21 0.03 0.18 0.19 0.08 0.03 Household type TY1 0.18 TY2 0.24 TY3 0.09 TY4 0.07 CH15 0.33 0.15 0.24 0.09 0.08 0.34 0.27 0.25 0.08 0.05 0.30 0.25 0.26 0.08 0.05 0.30 0.25 0.26 0.08 0.06 0.31 NOTE: See Table 1 for the list of definitions of the variables. 0.23 0.26 0.08 0.07 0.31 0.22 0.23 0.07 0.08 0.33 0.18 0.24 0.06 0.09 0.34 0.20 0.24 0.06 0.08 0.37 0.18 0.25 0.06 0.09 0.39 0.24 0.23 0.08 0.06 0.34 0.21 0.25 0.08 0.06 0.30 71 72 FAMILY AND CONSUMER SCIENCES RESEARCH JOURNAL TABLE 3: Lottery Expenditures by Region in Canada Region Atlantic Canada Quebec British Columbia Ontario Alberta Manitoba/Saskatchewan % of Households Buying Lottery 78.9 86.1 79.9 78.3 82.7 81.5 Lottery Expenditures as a % of Household Income 0.82 0.80 0.67 0.72 0.81 0.86 presence of children younger than 15 years of age, are measured for the entire household. For the categorical variables of education, occupation, and type of household, the following were used as reference groups: reference person has less than high school education; reference person is not working or retired; and married couple households with unmarried children only, married couple households with relatives only and/or with at least one nonrelative. On a per household basis, residents of Alberta, Manitoba/Saskatchewan, and Ontario are the most prolific gamblers in terms of Canadian dollars wagered annually ($300.07, $270.97, $260.56 for the whole sample, and $362.82, $332.47, and $332.78 for lottery players in the respective regions). Table 3 shows the percentage of households that purchased lottery tickets as well as the average expenditures of these households as a percentage of after-tax income. The column “% of Households Buying Lottery” in Table 3 shows that participation rates ranged from a high of 86.1% of all households in Quebec to a low of 78.3% in Ontario. It is interesting to note that these rates are higher than those reported by Kitchen and Powells (1991) for the same regions a decade earlier. The second column, “Lottery Expenditures as a % of Household Income,” reports total lottery expenditures as a percentage of after-tax household income for all households engaging in lottery expenditures. The percentage ranged from 0.67 for households residing in British Columbia to 0.86 for households residing in Manitoba/Saskatchewan. The estimates of the effects of the independent variables on the participation (purchasing or not purchasing lottery tickets) and expenditurelevel decisions of the participants on a region-by-region basis are shown in Table 4. The results indicate that the probability of participation in the lottery is positively related to household after-tax income in all regions, with the exception of Quebec and Alberta. Household Abdel-Ghany, Sharpe / LOTTERY EXPENDITURES IN CANADA 73 wealth and place of residence (urban vs. rural) have no discernible effect on whether a household purchases lottery tickets. Participation in the lottery decreases with age in Alberta; however, age does not significantly affect lottery participation in all remaining regions. College graduates are less likely to be lottery players in the regions of Quebec, British Columbia, and Ontario. Born Canadians are more likely to participate in lottery purchases than immigrants in the regions of British Columbia and Manitoba/Saskatchewan. The type of occupation has a varying effect on the probability of being a lottery player. Single persons are less likely to participate in lottery purchases in all regions, with the exception of Alberta and Manitoba/Saskatchewan. Also, lone-parent households are less likely to be lottery players in the regions of Quebec and Ontario. Having children younger than the age of 15 reduces the probability of the household to participate in lottery purchase in the Atlantic region as well as Quebec and Ontario. Table 4 also presents the estimates of the effects of the independent variables on how much households actually spend on lottery. After-tax household income is positively related to influence on the level of expenditures on lottery purchases across all regions, with the exception of Quebec. These results are consistent with the results of the study by Kitchen and Powells (1991), in which income level was found significantly to influence lottery expenditures in all regions. The relationship between wealth and household lottery expenditures is positively statistically significant for households residing in Quebec; however, the relationship is negatively related in Manitoba/Saskatchewan. Kitchen and Powells (1991) found that wealth was negatively related to the amount spent on lottery purchases in four of the regions, with the exception of Quebec and Alberta. The age of the reference person is positively related to lottery expenditures and statistically significant in British Columbia, Ontario, and Alberta, and insignificant elsewhere. Whereas households in urban areas in British Columbia spend significantly less on lottery purchases, households in urban Manitoba/Saskatchewan spend significantly less than their rural counterparts on lottery purchases. The results broadly indicate that education has a negative effect on lottery expenditures. More specifically, households in which the reference person had some college education spent significantly less on lottery tickets than households in which the head had less than high school education in all regions, with the exceptions of British 74 TABLE 4: Estimation of Participation and Level of Expenditures on Lottery in Canada Atlantic Canada Quebec Lottery British Columbia Lottery Ontario Lottery Alberta Lottery Manitoba/ Saskatchewan Lottery Lottery Probability Expenditures Probability Expenditures Probability Expenditures Probability Expenditures Probability Expenditures Probability Expenditures of Lottery Among of Lottery Among of Lottery Among of Lottery Among of Lottery Among of Lottery Among Participation Participants Participation Participants Participation Participants Participation Participants Participation Participants Participation Participants n = 2,350 Intercept HI HW Age Urban Education ED1 ED2 ED3 CB1 n = 1,877 0.574* 225.01 (0.270) (124.31) 0.121*** 24.59** (0.024) (8.423) –0.003 –4.312 (0.008) (3.514) –0.002 2.23 (0.003) (1.433) 0.039 56.49 (0.071) (32.00) 0.037 (0.090) 0.148 (0.106) –0.266 (0.145) 0.070 (0.134) n = 1,545 n = 1,330 n = 1,448 0.460 (0.351) 0.039 (0.028) –0.004 (0.009) 0.006 (0.009) 0.179 (0.128) 154.10 (146.75) 20.07 (10.81) 8.06* (3.88) 1.36 (1.69) 131.73* (52.84) 0.264 (0.344) 0.051* (0.022) –0.001 (0.003) 0.005 (0.004) 0.150 (0.155) –76.43 (49.62) –163.40** (57.25) –191.66** (76.37) –8.06 (55.32) –0.123 65.57 (0.161) (70.58) –0.163 –120.87 (0.167) (73.31) –0.614*** –188.92* (0.184) (86.23) 0.306*** 81.33* (0.086) (40.71) –78.54 0.165 (44.45) (0.122) –163.80*** 0.068 (49.40) (0.140) –222.19*** –0.370* (66.27) (0.176) 62.34 0.206 (61.46) (0.162) n = 1,157 n = 2,396 n = 1,882 66.09 0.683** 43.56 (156.22) (0.263) (158.92) 28.81** 0.078*** 28.34** (9.50) (0.017) (9.56) 0.174 –0.007 –3.25 (1.518) (0.004) (2.31) 4.59** –0.001 4.68** (1.70) (0.003) (1.83) –151.46* –0.042 62.60 (69.77) (0.131) (72.69) –0.057 –48.00 (0.098) (63.08) –0.096 –139.93* (0.109) (69.78) –0.321** –264.24*** (0.126) (81.10) 0.225*** 98.10* (0.066) (41.16) n = 821 n = 679 n = 1,519 n = 1,234 1.325** (0.538) 0.044 (0.028) –0.82E-04 (0.008) –0.016** (0.006) –0.084 (0.201) –207.42 (327.31) 60.65*** (15.77) –8.79 (5.13) 7.03* (3.43) –25.46 (118.47) –0.118 157.42 (0.328) (178.33) 0.152*** 27.35* (0.029) (12.46) –0.008 –12.14** (0.009) (4.61) –0.002 2.66 (0.004) (1.98) –0.039 187.21*** (0.118) (58.32) 0.351 (0.199) –0.336 (0.214) –0.190 (0.236) 0.204 (0.128) 304.95* (142.09) 57.25 (149.00) –16.77 (168.93) 9.87 (84.68) 0.055 (0.120) 0.043 (0.139) –0.340 (0.167) 0.326** (0.105) –99.09 (65.21) –295.85*** (73.86) –302.04*** (89.43) 164.36** (60.31) Occupation OC1 0.220 –87.36 (0.125) (54.12) OC2 0.235 –80.17 (0.209) (91.01) OC3 0.359** –19.23 (0.114) (48.94) OC4 0.259* 48.00 (0.112) (49.15) OC5 0.184 3.67 (0.139) (60.34) OC6 –0.237 –68.87 (0.225) (114.10) 0.387* (0.163) –0.102 (0.226) 0.517*** (0.149) 0.444** (0.62) 0.522** (0.195) –0.170 (0.400) Household type TY1 –0.506*** (0.121) TY2 –0.171 (0.108) TY3 0.147 (0.126) TY4 –0.151 (0.138) CH15 –0.315** (0.101) –0.599*** –1.69 (0.169) (61.96) –0.213 –29.89 (0.167) (55.73) –0.370* –83.14 (0.164) (69.47) –0.366 17.51 (0.212) (82.74) –0.387** –76.61 (0.152) (53.59) –148.06** (53.92) –50.13 (42.91) –102.85 (54.74) 98.57 (57.15) –101.70** (39.93) –63.47 (66.06) –75.38 (109.07) –15.88 (58.67) –13.44 (62.58) 61.00 (69.93) –113.61 (192.07) 0.314* 33.97 (0.148) (67.56) –0.850** –45.75 (0.296) (119.20) 0.321* –7.93 (0.140) (62.94) 0.250 6.80 (0.152) (67.77) 0.451* 34.59 (0.216) (86.98) –0.065 –119.34 (0.202) (103.11) 0.186* 22.24 (0.112) (69.58) –0.077 –114.64 (0.190) (124.41) 0.227* 50.56 (0.106) (66.81) 0.513*** 119.22 (0.119) (66.83) 0.250 76.08 (0.132) (46.99) –0.153 9.70 (0.220) (161.57) –0.125 (0.208) 0.333 (0.363) 0.159 (0.212) –0.030 (0.210) 0.213 (0.301) –0.009 (0.358) –88.32 (133.82) –121.80 (218.68) –11.39 (129.49) 70.87 (132.17) –185.70 (163.51) –215.24 (224.57) –0.189 100.07 (0.150) (78.38) 0.320 –101.54 (0.259) (130.62) 0.338* 6.63 (0.144) (74.59) 0.308* 132.73 (0.149) (76.48) 0.448* –63.36 (0.194) (90.84) –0.108 41.30 (0.234) (124.20) –0.425** (0.160) –1.109 (0.148) –0.078 (0.166) –0.101 (0.203) –0.091 (0.137) –0.603*** –180.84** (0.121) (72.24) –0.197 –116.04* (0.111) (60.22) –0.447*** –97.30 (0.123) (82.37) –0.039 28.62 (0.138) (74.95) –0.282** –105.82* (0.101) (55.05) –0.231 (0.220) 0.008 (0.201) –0.297 (0.229) 0.128 (0.259) –0.184 (0.186) –100.94 (135.85) 25.47 (117.73) –174.02 (150.28) –78.35 (137.78) –72.36 (107.14) –0.087 (0.157) 0.161 (0.146) 0.017 (0.157) 0.146 (0.194) –0.023 (0.135) NOTE: See Table 1 for the list of definitions of the variables. *p > .05. **p > .01. ***p > .001. –29.87 (70.04) 52.97 (61.23) –73.22 (73.02) 207.55** (82.42) –35.21 (56.50) –274.44*** (80.67) –111.72 (68.25) –113.13 (82.08) –77.09 (93.21) –215.54*** (63.28) 75 76 FAMILY AND CONSUMER SCIENCES RESEARCH JOURNAL Columbia and Alberta. In all regions with the exception of Alberta, reference persons with college degrees also spent significantly less than those with less than high school education. These results are broadly consistent with previous studies (Clotfelter & Cook, 1987, 1989; Kitchen & Powells, 1991; Livernois, 1987; Scott & Garen, 1994; Stranahan & Borg, 1998). Born Canadians spent significantly more on lottery tickets than immigrants in the regions of British Columbia, Ontario, and Manitoba/ Saskatchewan. The type of occupation held by the reference person was limited in affecting the level of expenditures on lottery in all regions. Only in Ontario, the group for which the occupation of the reference person was designated as farming, fishing, mining, and so forth, spent significantly more than the retired and unemployed group. Lone-person households spent significantly less on lottery purchases than married-couple households with unmarried children in the Atlantic region of Canada, Ontario, and Manitoba/Saskatchewan. Also in Ontario, married-couple households only spent significantly less than married-couple households with unmarried children. The presence of children younger than the age of 15 in the household has a negative effect on the amount of money spent on lottery tickets in the Atlantic region of Canada as well as in Ontario and Manitoba/ Saskatchewan. The question of who bears the burden of state lotteries, or in the language of economists, the question of the incidence of lottery finance, has been the most frequently researched issue related to the lottery. Some researchers argue that the revenue the state keeps from lottery sales is a tax. Others argue to the contrary, that because there is no coercion involved and that people voluntarily participate in the lottery, it should not be considered as a tax (Livernois, 1986; Stranahan & Borg, 1998; Zorn, 1988). The regressivity of the lottery can be examined by estimating the income elasticity of lottery expenditures at the mean. For example, a 10% increase in after-tax income for a household residing in the Atlantic region of Canada with the sample’s mean income of $37,620 increases yearly lottery expenditures from $309.42 to $318.67, which is an increase of only 2.99%. This means that the income elasticity of lottery expenditures at the mean is only 0.299, and an income elasticity of less than 1 denotes a regressive pattern of expenditures, which leads to a regressive tax. Abdel-Ghany, Sharpe / LOTTERY EXPENDITURES IN CANADA 77 The application of the same above procedure yields an income elasticity of lottery expenditures at the mean of 0.250 (Quebec), 0.427 (British Columbia), 0.391 (Ontario), 0.751 (Alberta), and 0.318 (Manitoba/Saskatchewan). As can be noted, the income elasticity of lottery expenditures across all regions is less than 1, denoting a regressive pattern of expenditures, which implies a regressive tax. CONCLUSION Provinces currently retain 80 to 85% of gambling revenue in Canada, whereas charities share 15 to 20% of this revenue (Canadian West Foundation, 2000). Given the tremendous growth in the lottery system in Canada since its legalization in the early 1970s, the Canadian provinces are relying more heavily on its generated funds. Results of this study indicate that the factors associated with the decision to participate in the lottery do not necessarily have the same influence on the level of expenditure on lottery for those who choose to participate. Consequently, this study provides valuable information to lottery administrators in the different provinces of Canada for designing programs to either recruit new lottery players or to increase spending for those who already participate in the purchasing of lottery tickets. Whereas some household characteristics (wealth and place of residence) do not affect the probability of a particular household to participate in lottery playing in every province, others vary in the extent to which they significantly affect such a probability. Similarly, the profile of those players who spend more on lottery playing can be drawn from the results. In general, lottery expenditures increase as household after-tax incomes increase, and lottery expenditures decline as the education level of the reference person increases. Other household characteristics affect the level of spending on the lottery variably among the provinces. For those variables exhibiting regional variations, their effect should be considered before designing regional plans. The results also indicate that the percentage of after-tax income spent on lottery declines as income increases in every region. Therefore, from the standpoint of public policy makers, we conclude that the lottery tax in Canada is regressive. 78 FAMILY AND CONSUMER SCIENCES RESEARCH JOURNAL REFERENCES Borg, M. O., & Mason, P. M. (1988). The budgetary incidence of a lottery to support education. National Tax Journal, 61, 75-85. Brinner, R. E., & Clotfelter, C. T. (1975). An economic appraisal of state lotteries. National Tax Journal, 28, 395-404. Canadian West Foundation. (2000). Canadian gambling behaviour and attitudes [Online]. Available: www.cwf.ca/pubs/200001.cfm?pub_id=200001 Clotfelter, C. T. (1979). On the regressivity of state-operated “numbers” games. National Tax Journal, 32, 543-548. Clotfelter, C. T., & Cook, P. J. (1987). Implicit taxation in lottery finance. National Tax Journal, 40, 533-546. Clotfelter, C. T., & Cook, P. J. (1989). Selling hope: State lotteries in America. Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. Cragg, J. G. (1971). Some statistical models for limited dependent variables with applications to the demand for durable goods. Econometrica, 39, 829-844. Greene, W. H. (1993). Econometric analysis (2nd ed.). New York: MacMillian. Greene, W. H. (1995). LIMDEP Version 7 [Computer software]. New York: Econometric Software. Hansen, A. (1995). The tax incidence of the Colorado State lottery instant game. Public Finance Quarterly, 23, 385-398. Hansen, A., Miyazaki, A. D., & Sprott, D. E. (2000). The tax incidence of lotteries: Evidence from five states. The Journal of Consumer Affairs, 34, 182-203. Heavey, J. F. (1978). The incidence of state lottery taxes. Public Finance Quarterly, 6, 415-426. Kitchen, H., & Powells, S. (1991). Lottery expenditures in Canada: Aregional analysis of determinants and incidence. Applied Economics, 23, 1845-1852. Livernois, J. R. (1986). The taxing game of lotteries in Canada. Canadian Public Policy, 12, 622-627. Livernois, J. R. (1987). The redistributive effects of lotteries: Evidence from Canada. Public Finance Quarterly, 15, 339-351. Mikesell, J. L. (1989). A note on the changing incidence of state lottery finance. Social Science Quarterly, 70, 513-521. North American Association of State and Provincial Lotteries. (2000a). Did you know? [Online]. Available: www.naspl.org/faq.html North American Association of State and Provincial Lotteries. (2000b). NASPL members–Western Canada [Online]. Available: www.naspl.org/states/wclc.html Scott, F., & Garen, J. (1994). Probability of purchase, amount of purchase, and the demographic incidence of the lottery tax. Journal of Public Economics, 54, 121-143. Spiro, M. H. (1974). On the tax incidence of the Pennsylvania lottery. National Tax Journal, 27, 57-61. Statistics Canada. (1996). Microdata files [Electronic database]. Survey of Family Expenditures, 1996. Ottawa, Ontario: Household Surveys Division, Statistics Canada. Stranahan, H. A., & Borg, M. O. (1998). Separating the decisions of lottery expenditures and participation: A truncated approach. Public Finance Review, 26, 99-117. Suits, D. B. (1977). Gambling taxes: Regressivity and revenue potential. National Tax Journal, 1, 19-35. Zorn, C. K. (1988). The lottery: Its economic effects. Indiana Business Review, 63, 4-5.