DP

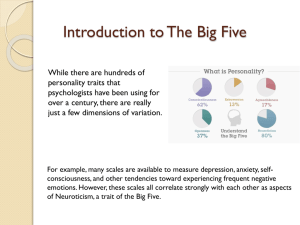

advertisement