DP The Effects of Birth Weight: RIETI Discussion Paper Series 13-E-035

advertisement

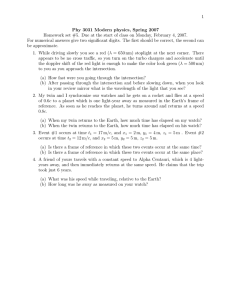

DP RIETI Discussion Paper Series 13-E-035 The Effects of Birth Weight: Does fetal origin really matter for long-run outcomes? NAKAMURO Makiko Keio University UZUKI Yuka National Institute for Educational Policy Research INUI Tomohiko RIETI The Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry http://www.rieti.go.jp/en/ RIETI Discussion Paper Series 13-E-035 April 2013 The Effects of Birth Weight: Does fetal origin really matter for long-run outcomes? 1 NAKAMURO Makiko (Keio University) 2 UZUKI Yuka (National Institute for Educational Policy Research) & INUI Tomohiko (Nihon University / RIETI) Abstract This paper investigates whether birth weight itself causes individuals’ future life chances. By using a sample of twins in Japan and controlling for the potential effects of genes and family backgrounds, we examine the effect of birth weight on later educational and economic outcomes. The most important finding is that birth weight has a causal effect on academic achievement at around the age of 15, but not on the highest years of schooling and earnings. Keywords: Birth weight, Nutritional intake, Identical twins, Endogeneity JEL classification codes: I10, I20 RIETI Discussion Papers Series aims at widely disseminating research results in the form of professional papers, thereby stimulating lively discussion. The views expressed in the papers are solely those of the author(s), and do not represent those of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry. 1 This study was conducted as part of a project titled “Research on Measuring Productivity in the Service Industries and Identifying the Driving Factors for Productivity Growth” of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade, and Industry (RIETI). We gratefully acknowledge that this research was financially supported by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A) titled “The Assessments of the Quality and the Productivity of Non-marketable Services” (Research Representative: Takeshi Hiromatsu, No. 3243044). 2 Corresponding author: Makiko Nakamuro, Faculty of Policy Management, Keio University, e-mail: makikon@sfc.keio.ac.jp. The authors would like to thank Atsushi Nakajima, Masahisa Fujita, Masayuki Morikawa, Keiichiro Oda, Yoshimichi Sato, Shinji Yamagata, Daiji Kawaguchi, Andrew Griffen and other participants of Tokyo labor economics workshop for their insightful comments and suggestions on the draft of this paper. All the remaining errors are ours. 1 Introduction Itwouldbegenerallybettertohaveasmallbabyatbirthandthenraise him/hertogrowbiglaterinlife–thishaslongbeenbelievedtobegoodpracticein child‐bearinginJapan.BeforeC‐sectiondeliveryorotherobstetricprocedures becamepopularthroughoutsociety,peopleperhapsaimedtoreducetheriskof endangeringmothers’livesbygivingbirthtoasmallbaby.Thiswidespreadbelief seemstobestilldominanttoday.However,itisunexpectedlylittleknownthat thereisahiddenriskofhavingasmallbaby:recentresearchhasfoundthatlow birthweightissignificantlyassociatedwithbothshort‐andlong‐runadult outcomes,suchasinfantmortality,studentachievements,andadulthoodhealth (Conley&Bennett(2000);Linnetetal(2006);Currie&Hyson(1999),etc.). Whyisthishappening?Lowbirthweightiscausedbypretermdeliveryor lowfetalgrowththatmayreflectvariationinnutritionalintakeinthewomb. Low‐birthweightisthusrecognizedastheleadingindicatorofpoorhealthamong infants,whichmaydelaybrainandsomaticdevelopmentandthenaffectawide rangeofsubsequentoutcomeslaterinlife.Thismechanismhasbeenalsorapidly revealedasanobjectofepigenetics(e.g.,Petronis,2010etc.).Liketheresults drawnfromdatainU.S.,DenmarkandEngland,Kohara&Ohtake(2009)used officialstatisticsfromtheVitalStatisticsandtheNationalAssessmentofAcademic AbilityinJapanandfoundanegativecorrelationbetweenbirthweightand academicachievementsmeasuredbystandardizedtestscoresinG6andG9atthe prefecturelevel.Ifthisisthecase,cantherebeanydoubtthattheGovernmentof Japanmustshapeapolicyagendatoincreasethebirthweightofnewbornbabies, forexample,throughimprovementsinthehealthofpregnantmothers? Unfortunately,however,thereisnosimpleanswertothisquestion. Whilemuchisknownaboutthecross‐sectionalcorrelationbetweenbirth weightandadulthoodoutcomes,littleisknownregardingtheextenttowhatwould havehappentoanindividualoutcomeifapersonwhowasactuallybornwitha heavierbirthweighthadbeenbornwithalighterbirthweight.Inotherwords,itis highlypossiblethatobserveddifferencesinbirthweightsamongnew‐borninfants maysimplyreflectunobservedparentalcharacteristicswhicharealsocorrelated withadulthoodoutcomesofanindividual:aselectionbiasariseswhenpartof individualoutcomescanbeexplainedbyunobservedparentalcharacteristics. Observedcorrelationsusingcross‐sectionaldatainpreviousliteraturethusdidnot 2 provideafulldescriptionoftheeffectofbirthweightandresultinbiasedand inconsistentestimates. Inthisresearch,wewouldliketoanswerthequestionsofwhetherbirth weightitselfcausesindividuals’adulthoodoutcomeslateroninlife.Causalityis thusobviouslythekey.Oneoftheinnovativemethodsthatsocialscientistshave employedinrecentyearsaddressthecausalrelationshipbetweenbirthweightand adulthoodoutcomesistouseasampleoftwins(orsometimessiblings).Infact, manyeconomists,suchasBerhman&Rosenzweig(2004),Royer(2009),Almond etal(2005)fortheU.S.,Milleretal(2005)forAustralia;Lawloretal(2006)for Scotland;Oreopoulosetal(2006)forCanada,andBlacketal(2007)forNorway (seeCurrie(2009)foramorecomprehensivesurvey)useadatasetcontaining informationontwin‐pairsandattempttocopewiththeproblemofunobserved differencesinabilityandfamilyenvironments.Theseconsiderableeffortshave beendedicatedtouncoveringtheeffectofbirthweightonadulthoodoutcomes: previousresearchreachedaconsensusthatbirthweightdoesmatterbothinthe short‐andlong‐run. Wealsofollowthisapproachtodealwiththeaforementionedbias, comparingthedifferencesbetweentwin‐pairstoisolatethepureeffectofbirth weightontheadulthoodoutcomes,holdinginnateabilitiesandfamily environmentsconstant.Anotheradvantageofusingasampleoftwinsisthat, becausetwinpairshavethesamegestationlength,thedifferencesinbirthweight betweentwinsareattributedsolelytodifferencesinfetalgrowthrates.Themain researchquestionofinterestinthispaperisthus:doesnutritionintakeinutero reallymatterforone’slifechance?Ifso,whichstageofone’slifeisthemost affected? Tothebestofourknowledge,thecaseofJapanisrelativelyunexploreddue tothedatalimitation.Thisisunfortunategiventherecentvariablefindingsin Japanthatlowbirthweightisassociatedwithparentalsocioeconomicfactors,such asthemother’ssmokinghabitsandemploymentstatus(Tsukamotoetal,2007; Kawaguchi&Noguchi,2012betc.).Theunderstandingofwhetheranindividual inheritshis/herparentalsocioeconomicstatusatfetaloriginwouldcontributeto furtherdiscussionoftheintergenerationaltransmissionmechanismofsocial stratification,towhichpolicycirclesmaypayconsiderableattention.Inthisstudy, wetakeadvantageoftheuniquetwins‐datasetsthattheauthorshavecollectedin Japanthroughaweb‐basedsurvey. Toanswerourresearchquestion,wefollowtheprotocolofprevious 3 literatureandoutlineatwin‐fixedeffectstrategyusingasampleofmonozygotic twins(hereafter,MZtwins)whoaregeneticallyidentical.However,interestingly, thereisavariationinbirthweightbetweentwin‐pairsingeneral.Aspointedoutby AshenfelterandRouse(1998),first‐borntwinsareusuallyheavierthantheir second‐bornsiblingsatbirth.Thissettingallowsustocreateacounterfactual situationofwhatwouldhavehappenedtoadulthoodoutcomesofapairoftwin whowerebornwithalowerbirthweightifs/hehadbeenbornwithaheavier birthweightinstead.Wethensetupfivemainoutcomestobeexamined:(i) participationinprivate(ornational)middleschools;(ii)studentperformanceat theageofaround15;(iii)rankingatthecollegeattended;(iv)yearsofschooling; and(v)earnings.Thesignificantfindinginthispaperisthatbirthweightonly causesacademicachievementundertheageof15.Unlikesomeoftheevidence fromwesterncountries,thiseffectsubsequentlydisappears.Ourempiricalresults showthatfetalgrowthmayaffectstudentperformanceinyoungchildren,butit doesnotdirectlyaffecthis/heradulthoodoutcomesinlaterlife,suchas educationalattainmentsandearnings. Therestofthispaperisorganizedasfollows:thenextsectionreviews relevantliteraturetosortoutinformationonwhatwestilldonotknowand explainshowwetackledthemethodologicalproblemsinpreviousresearch.The followingsectionsintroducetheempiricalspecificationstobeestimated,identify thepotentialbiasemergingintheeconometricanalysis,anddeterminethe analyticaltechniquestobeusedtoidentifythecausalimpactofbirthweighton adulthoodoutcomelaterinlife.Theninthefinalsection,wedescribetheunique twinsdatasetusedforempiricalanalysisandpresenttheempiricalresults. RelevantLiterature Evidencetoshowwhetherandtowhatextentincreasingthebirthweight ofnewborninfantscanimprovetheirfuturelifechanceswouldbeusefulfor framinganappropriatepolicydirectionregardingthenutritionalintakeof expectantmothers.Agrowingbodyofresearchhasattemptedtoidentifythe causaleffectsofbirthweightonnotonlyshort‐termbutalsolong‐termoutcomes bytheuseoftwindata.Suchdataenablesresearcherstoruleoutthepotential influencesofgeneticmakeupandfamilybackgroundsthataffectbothbirthweight andlateroutcomesandtoobtainbetterestimatesofthecausaleffectsofbirth weightthanthosederivedfromconventionalcross‐sectionalanalysis.Inthis 4 section,wereviewtherelevantliteratureinvestigatingthecausaleffectofbirth weightoneducationalandeconomicoutcomes,inparticularbyusingtwindata. Regardingeducationaloutcomes,thereisevidencebasedontwinstudies thatbirthweighthasalong‐termimpact.BehrmanandRosenzweig(2004),Black etal.(2005)andOreopoulosetal.(2008),usingtwindatafromMinnesota,Norway andManitoba,respectively,foundthatbirthweighthasapositiveeffectonhigh schoolcompletion.LinandLiu(2009)analyzedTaiwanesetwindataandfound thatbirthweightincreasedgradesatage15.ItisnoteworthythatBehrmanand Rosenzweig(2004)andLinandLiu(2009)showedthattheOLScoefficientsfor birthweightwithoutcontrollingforgenesandfamilybackgroundsare underestimatedby50%,whileBlacketal.(2005)foundthatOLSestimatesand twin‐fixedeffectsaresimilarinsize.BehrmanandRosenzweig(2004)andLinand Liu(2009)arguethattheirfindingssuggestthatparentsmayinvestmoreinlighter twinstomakeupfortheirdevelopmentaldisadvantage. However,somestudiessuggestthattheeffectofbirthweightonyearsof schoolingisrathersmall(Royer,2009)orthatthereisnosignificantrelationship betweenbirthweightandeducationalattainmentorcognitiveabilitymeasuredby languagetestscores(Milleretal.,2005;Oreopoulosetal.,2008).Itremains unclearwhetherthismixedevidenceisduetodifferencesinmeasuresregarding educationaloutcomesordatasources. Thereisrelativelylessevidenceonthedirecteffectofbirthweighton economicoutcomes.Milleretal.(2005)areoneoftheexceptionalgroupsof researcherswhofoundapositive,directeffectofbirthweightonearnings,but arguethatbirthweightplaysonlyaminorroleindeterminingearnings,witheach additionalounceofbirthweightincreasingearningsby0.4%.Otherstudiesthat examinetheeffectofbirthweightoneconomicoutcomesincludeRoyer(2009)and Oreopoulosetal.(2008).However,Royer(2009)didnotfindevidencetoshowthat birthweightisassociatedwithneighborhoodincomelevelsinadulthood. AlthoughOreopoulosetal.(2008)foundthatbirthweightaffectssocialassistance takeupandlengthinadulthood,butgiventhattheyalsofoundtheeffectofbirth weightonhighschoolcompletion,itisunclearwhetherthebirthweighteffecton economicoutcomeswouldremainaftercontrollingforthemediatingeffectof educationaloutcomes. InJapan,noresearchhasusedtwindatatoinvestigatethecausaleffectof birthweightoneducationalandeconomicoutcomesinadulthood.Themost importantreferenceworkisanon‐twinstudyconductedbyKawaguchiand 5 Noguchi(2012b),analyzingearlychildhooddatafromtheLongitudinalSurveyof Babiesinthe21stCentury.Theyfoundthatlowbirthweight,definedasaweight below2,500grams,isassociatedwithadelayindevelopmentatagetwoandahalf, butnotwithbehaviorsatagesixandahalf.Apossiblereasonfortheassociation disappearingatanolderagemaybethefactthatJapaneseparentsinvestmorein theirchildreniftheirdevelopmentisobservedtobeslowatanearlierstage. Therefore,thisevidencedoesnotconfirmwhetherthebirthweighteffectremains onlyforashortperiodoftimeinJapan.Furthermore,littleisknownaboutthe effectofbirthweightonmuchlatereducationalandeconomicoutcomesinJapan. WeaimtofurthertheliteraturebyusingJapanesetwindatatobringout newfindingsinthefollowingthreerespects.Firstlyandmostimportantly,wewill estimatetheeffectsofbirthweightbyaddressing,forthefirsttimeinJapan, potentialendogeneitybiasesduetotheeffectsonbirthweight,post‐natal developmentandlateroutcomesofgenesandparentalbehaviorsusually associatedwithafamily’ssocio‐economicstatus.Secondly,wewillinvestigate longer‐termeducationalandeconomicoutcomesashasbeendoneinrelevant previousresearchinJapan,whichmayleadtoinsightintohowlong‐lastingthe birthweighteffectswouldbe.Lastly,wewillexamineeducationaloutcomes measuredinseveralwaysforthesamesample,whichmaycontributetoclarifying whicheducationaloutcomesshouldbehighlighted,giventhecurrentmixed evidenceacrosstheworldontheeffectsofbirthweightoneducationaloutcomes. EmpiricalSettings Inordertoaddressourresearchquestionsofhowbirthweightaffects adulthoodoutcomes,webegintheanalysisusingaconventionalOLStoreportthe cross‐sectionalcorrelationswiththeentiretwinsample,inwhichmanyprior studieshavefoundthatthebirthweightisstronglyassociatedwithawiderangeof adulthoodoutcomes.Followingthepreviousliterature,weoutlinethesimple educationproductionfunctionillustratingtheinput‐outputrelationshipathomeor schoolthatparticularlyhighlightstheroleofchildhealth.Themodelcanbe formallyexpressedinthefollowingmathematicalequationwhereyisoutcomes andisafunctionofthebirthweight(bw)andunobservables(A),suchasgenetic makeupormaternal/pre‐natalcareincombinationwithothercharacteristics(X) andrandomdisturbancewithmeanzeroandconstantvariance(e)asspecifiedin theequation(1)and(2)below.Notethatthefirst‐borntwinisdenotedas1bya 6 subscriptandthesecond‐bornas2. ′ ′ (1) (2) Thecoefficientofβreferstotheeffectofthebirthweightonoutcomevariables holdingotherobservedcharacteristicsconstant.Aswediscussedearlier,the cross‐sectionalestimateofβmaybebiasedandinconsistentbecause unobservables,Aij,affectboththebirthweightandoutcomes.However,identical twinsenableustosetupA1j=A2j,giventhattheysharegeneticmakeupandfamily environments.Wewillthustakeatwinfixedeffectapproachtakingthedifference betweenequation(1)and(2)toobtainawithin‐twinfixedeffectsestimateofβ, yielding: ) (3) Inequation(3),unobservable,Aj,iseliminated,relievingusoftheconcernthatthe outcomesarepartlyexplainedbyindividualunobservedcharacteristics.Giventhe assumptionthattheerrortermisanidiosyncratic,whichisindependentofall othertermsintheequation,βisconsideredastheconsistentestimate. Data Thedatausedforourempiricalanalysiswascollectedthrougha web‐basedsurveyinJapanbetweenthemonthsofFebruaryandMarch2012(see Nakamuro&Inui(2012)formoredetailedinformationonthedatacollection strategy).Weconductedthesurveythroughaweb‐basedsurveycompany,Rakuten Research,withover2.2millionmonitors.Inordertoanalyzetheeffectofbirth weightonadulthoodoutcomes,oursampletargetedtwinswhoarenon‐students betweentheagesof20and60.Throughthisweb‐basedsurvey,onememberofa twinpairisresponsibleforreportingregardinghim/herselfandhis/hertwin siblingatonetime,andtheresultsaredesigneddifferentlyfromthoseoftheother twinsurveyfilledoutbybothmembersofthetwinpair3. 3 Onemayquestionthat,inoursurvey,theremayexistsubstantialmeasurementerrorsin self‐reportedbirthweightandotheroutcomesbyoneofthetwinpairs,insteadofboth.Itis importanttonotethatwehave23twinpairs,eachmemberofwhichwasincludedinthis survey.Whenwechecktheirresponses,wefindoutthattheirresponsesreportedbyeach 7 Oncethemonitor(s)filledoutthequestionnaires,theywouldbegivena certainamountofcash‐equivalent“points”thatcouldbespentonRakutenonline shopping.Inordertoexclude“fake”twins,whopretendtobetwinstocollectthe cash‐equivalentpoints,wecarefullydevelopedthefollowingdatacollection strategy:wedidnotinformrespondentsthatthepurposeofoursurveywasto collectdatafromtwins.Furthermore,westartedwithfivequestionsonfamilyand siblingsthatwerenotrelatedtotwinstatusandthen,inthesixthquestion,forthe firsttime,askedwhetherornotarespondentwasatwin.Iftherespondent answered“No”inthisquestion,s/hewouldbeautomaticallyexcludedfromthe survey.Wediscovered23twinpairs,eachmemberofwhichwasincludedinthis survey,thenthoroughlycheckedtheresponsesofbothtwins,andeliminatedoneof thetwinsrandomlyfromoursample.Ourweb‐basedsurveyovercamethe disadvantagesofthedatacollectioninpreviousliterature,suchassmallsample sizeordataattrition.Consequently,wecollected2,360completepairsoftwins (4,720individuals)while1,371twinpairs(2,742individuals)aremonozygotic (seeTable1).Tothebestofourknowledge,thisisoneofthelargestdatabasesof twinscompiledinJapannationwide,anditconveysawiderangeofsocioeconomic information. Variables Theindependentvariableofinterestis,ofcourse,birthweightforwhich wesetupseveralvariantsinthefollowingway:theprimarymeasureisthebirth weightwhichisself‐reportedbyoneofthetwin‐pair.Theresponsecategoryinthe originalquestionnairerangedfrom1(=lessthan1,500grams)to7(=morethan 4,500grams)and8(=don’tknow).Wesettheminimumto1,500andthe maximumto4,500grams.Thenwetookthemid‐valueforthecategoriesbetween 2(=1,750grams)and7(=4,250grams).Basedonthisvariable,wecreatetwo variantsofthekeyindependentvariables:avariantisthenaturallogarithmofthe otherarequiteaccurate:thecorrelationsbetweenself‐reportedandcross‐reportedbirth weightis91.2%.Notonlythebirthweightbutalsootheroutcomesshowover90%of correlations.Furthermore,wecheckwhetherthereexistsignificantdifferencesbetween responsesonhim/herselfandonhis/hertwinsiblings;forexample,onemaybedoubtfulthat respondentsarepronetopretendthattheirearningsoreducationarehigherthanthoseof theirtwinsiblings.However,accordingtotheresultdrawnfromtwosamplet‐testsfor differenceofthemeans,thereisnodifferencebetweenthem.Asafurtherrobustnesscheck,we includearespondentdummyinallspecifications,butthedummiesarestatistically insignificant. 8 birthweight.Theotherisdefinedasadichotomousvariablemeasuringthelow birthweight,codedas1ifthebirthweightismorethan2,500gramsandzero otherwise. ThedescriptivestatisticssummarizedinTable2showthattheaverage twinsinoursampleweighed2,441gramsatbirthandmorethanhalfofthemwere categorizedasinfantswithlowbirthweights.Assuggestedinpreviousliterature, ourdataillustratesadisparityinbirthweightbetweenthefirstandsecondbornof twins:theaveragebirthweightofthefirstbornis2,464gramswhilethatofthe secondbornis2,423grams,andthisdifferenceisstatisticallysignificantata5% level.Furthermore,ourdatashowsthat24.8%ofMZtwinpairsweredifferentin weightatbirth,whichiscruciallyimportanttoensureanaccurateestimateofthe twinfixedeffectsmodel.IfwerestrictthesampletothosewhoareMZtwins,we havequitesimilarresults(seeTable1‐a).Werunseparateregressionsforeach variantofthebirthweight:theexplanatorypowerassessedbyR2statisticsfrom withintwinfixed‐effectsestimationshelpsustochoosethebestpossibleoption amongthesethreevariantsofbirthweight,aspresentedinTable3. Wethencharacterizesixoutcomesrangingfromtheperiodofchildhoodto adulthood.Thefirstoutcomevariableisatypeofmiddleschoolattended,which aimstomeasurescholasticabilityinearlychildhood.Sometwelve‐year‐old childrenenrollinJapanprivatejuniorhighschoolsinsteadofpublicschools becausemostprivatejuniorhighschoolsrequirechildrentopassentrance examinations,whichareoftencompetitiveandselective.AccordingtotheSchool BasicSurveyadministeredbyMinistryofEducation,Culture,Sports,Scienceand Technology,theenrollmentrateofprivatejuniorhighschoolswas8%4 in2012, withaconsiderablegeographicalvariation.Whilethemajorityofchildrenand parentsdonotconsiderchoosingprivateschoolsatall,anon‐negligibleproportion ofchildrenandparentsinJapanhaverecognizedtheentranceexaminationsof privatejuniorhighschoolsasthefirstscreeningprocessthrougheducational institutions.Inoursurvey,weaskwhichtypeofmiddleschooltherespondentand his/hertwinsiblingsattended.17.1%ofrespondentswerestudentsofprivateand nationaljuniorhighschools,whichisslightlyhigherthanthepercentageshowed byofficialstatisticsnationwide.Thismayinpartbeduetothecharacteristicofour surveythatitismorelikelytogatherinformationfromresidentsinlarge 4 Thisnumberincludestheenrollmentrateofnationaljuniorhighschools.Nationaljunior highschoolsaregovernment‐ownedjuniorhighschools,mostlyaffiliatedwithnational universities.Theseschoolsalsorequireapplicantstopassentranceexaminationstoenroll. 9 metropolitanareas,suchasTokyoandOsaka.Moreover,10.9%ofMZtwins‐pairs attendeddifferenttypesofschool:forexample,oneattendedaprivateschooland theotherapublicschool.Thesecondoutcomevariableisstudentperformanceat middleschool,whichismeasuredona5point‐scale(1=lower;2=belowaverage; 3=average;4=aboveaverage;5=upper)basedonasubjectiveevaluationof respondents’andtheirtwin‐siblings’academicachievements. Thethirdoutcomeistherankingofthecollegeattendedwitharestricted sampleofcollege‐educatedrespondents.Oursurveyasksthenameofthehigh schoolwhererespondentsandtheirtwinsiblingsgraduated.Weconvertthis informationintoameasureofdeviationvalue(“hensachi”inJapanese),which representstherankingofeacheducationalinstitutionwithameanof50and standarddeviationof10byusingaseriesofdeviationvalues.Wematchthename ofcolleges/universitiesandthedeviationvalueofeachdepartmentofeach college/universitybyusingthedataset,“KawaijukuCollegeRankings”,calculated andreleasedin2011byKawaijuku,oneofthelargestcramschoolsinJapan. CollegeadmissionsinJapanaredeterminedalmostentirelybyperformancein writtenexaminationsadministeredbyeachinstitutionexceptforsomespecial admissionprograms,suchasathleticscholarshipprograms. Thefourthoutcomeisyearsofschooling.Toavoidthepossibilityof institutionalmisreporting,inouroriginalquestionnaire,welisteverytypeand levelofeducationalinstitution(26categories,including“don’tknow”),andthen askrespondentstoselectthehighestdegreeobtained.Thechoiceof“dropoutor stopped”wasinsertedbetweenthequestionsoneachtypeandlevelofinstitution inordertodisentanglecasesofleavingschoolwithoutadiploma.Incalculatingthe yearsofeducation,weassumethatthosewho“droppedout”or“stopped”finished halfoftheminimumrequiredyearstocompletetheeducationalinstitutionlast attended(e.g.,dropoutfromhighschool=10.5yearsofschooling). Itisimportanttonotethatourdatashowsthatthewithin‐twinvariations ineducationalexperiencesbecomelargerwiththepassageoftime:only5.9%or 10.9%oftwinpairsattendeddifferenttypesofschoolswhentheywereprimaryor middleschoolstudents.Eventually,38.4%oftwinpairsinoursampleacquired differentnumbersofyearsofeducation.Somemaywonderwhytwins,whoshare thesamegeneticmakeupandfamilyenvironment,eventuallyendupsodifferently intermsofeducationalbackgrounds.BoundandSolon(1999)andNeumark (1999)pointedoutthatevenifthewithin‐twinestimateisabletoremovethe effectofgeneticendowment,itdoesnotnecessarilymeanthatthewithin‐twin 10 estimatecompletelyeliminatesallaspectsofabilitybiastotheextentthatability goesbeyondgenes.Thepotentialendogeneitycouldbecausedbyunobserved differencesinabilitybetweentwin‐pairswhichmayresultfromdifferent experiencesinearlierchildhood.However,accordingtooursurvey,parentsare unlikelytotreattwinsdifferently,particularlyintermsofeducationalinvestment. Forexample,thereislittledifferenceinexperiencesofshadoweducationbetween twin‐pairs,whichmaybeacrucialpartofhouseholdexpendituresoneducationin Japan5.Oursurveyshowsthatthewithin‐twinvariationsinshadoweducationis quitesmall,asthewithin‐twinvariationsinformaleducationbecomelargerwith thepassageoftime(seeTable1‐b).Therefore,itcanbesaidthatwithin‐twin variationsdonotreflectanysystematicdifferenceintheparentaleducational strategyforeachtwin,whichoftenleadstodifferentexperiencesinearlier childhood. Thefifthoutcomeislabormarketperformancemeasuredbythenatural logarithmofannualwagebeforetaxdeductionsduringthe2010fiscalyear6.The responsecategoryintheoriginalquestionnairerangedfrom1(=noincome) through16(=morethan15millionJPY).Wesettheminimum(1=noincomeand 2=lessthan0.5millionJPY)tozeroandmaximum(16=morethan15millionJPY) to15millionJPY.Then,wetakethemidvalueforcategoriesbetween3(=0.5 million‐0.99millionJPY)and15(=10million‐14.99millionJPY). EmpiricalResults Table4presentstheresultsestimatedbyaconventionalOLStoreplicate thecorrelationalstudiesinpreviousliterature.Regardlessofthevariantof dependentvariables,birthweightsarestronglyassociatedwithadulthood outcomes,exceptforthetypeofmiddleschoolandrankingofcollegeattended. Theresultscoupledwiththepositivecoefficientssuggestthatbirthweightaffects themajorityofeducationaloutcomeslaterinlife,suchasstudentperformanceat theageofaround15andthehighestyearsofschooling,aswellasthelabormarket 5 AccordingtotheofficialstatisticsoftheMinistryofEducation,Culture,Sports,Scienceand Technology,alargepartofhouseholdexpendituresoneducationhasbeenspentonshadow educationinJapan.TheBenesseEducationalResearchandDevelopmentCentershowedin 2009thatapproximately20%ofelementaryandhighschoolstudentsand50%ofjuniorhigh schoolstudentsaccessedshadoweducation,suchascramschoolsorprepschools. 6 Thissurveyaskedaboutearningsduringthefiscalyearof2010,insteadof2011,because earningsduringthefiscalyearof2011couldhavebeenaffectedbytheGreatEastJapan EarthquakethatoccurredonMarch11,2011. 11 outcomemeasuredbyannualearnings.Theeffectseemsquitelarge:forexample, anextra100gramsinbirthweightraisesearningsinthelabormarketby5.3%on average.Takenasawhole,ourresultsareconsistentwiththemainstreamof previousliteratureshowingapositivecorrelationbetweenbirthweightand adulthoodoutcomes. Thenweanalyzetheeffectofbirthweightonadulthoodoutcomes concerningwhetherthedifferenceinweightatbirthissubstantialorreflectsthe factthatinfantswithlighterbirthweightsfundamentallydifferfromthoseoftheir counterpartswithheavierbirthweights.Asexplainedearlier,weemploythe twin‐fixedeffectstocomparethedifferencesbetweenMZtwinstoisolatethepure effectofbirthweightontheadulthoodoutcomes,holdinginnateabilitiesand familyenvironmentsconstant.Table5showsaquitedifferentstoryfrom conventionalOLSestimates.Theeffectofthebirthweightontheadulthood outcomesinthelongerrun,suchasthehighestyearsofeducationandearnings, appearstobestatisticallyinsignificantacrossmodels.However,theeffectstill remainsineducation:birthweightcausesacademicachievementattheageof around15.Itmayalsocausetheprobabilityofpassingaprivatejuniorhighschool andtherankingofcollegeinwhichtheyparticipated,althoughtheevidenceto supportthisisweak.Thetwin‐fixedeffectsestimatesaresubstantiallylargerthan thecross‐sectionalones. Thispaperhasthussucceededinansweringtheresearchquestion.Like theevidencegeneratedfromwesterncountries,ourfindingalsosuggestthatbirth weightaffectseducationaloutcomes,particularlystudentperformanceattheage ofaround15.Ontheotherhand,theeffectisnotlong‐lasting,andbirthweight doesnotaffectlonger‐runoutcomes,suchasthehighestyearsofschoolingand earnings.Strictlyspeaking,inthissense,birthweightitselfisnottheculpritwith respecttothemoredisadvantagedadulthoodoutcomes. Conclusion Thispaperhasinvestigatedthequestionofwhethertheeffectsofbirth weightonlatereducationalandeconomicoutcomes,ifany,arecausal.Byusing datafromasampleoftwinsinJapan,wehaveprovidedbestavailableestimatesfor thecausaleffectsofbirthweightonacademicachievementattheageofaround15. Wewouldberathercautiousaboutconcludingthatbirthweightdoesnotaffect longer‐runoutcomes,suchashighestyearsofschoolingandearnings.Future 12 researchshouldexaminewhetherthisisalsothecasewhereeducational attainmentmeasuredbyeducationalqualificationsobtained,orwhereearningsare measuredwithsmallermeasurementerrorsthanwithself‐reportedearnings. Giventhatthemostplausiblefactoraffectingbirthweightdifferences betweenMZtwinsisintrauterinenutrientintake,ourfindingssuggestthat improvingpregnantmothers’nutrientintakemayleadtotheimprovementof educationaloutcomesatage15,therebyimprovingfuturelifechances. KawaguchiandNoguchi(2012a)arguedthatthedecreaseintheaveragebirth weightbetween1990and2005couldbepartlyexplainedbymedicalinstructions offeredtopregnantmothers.Thisimpliesthatincreasingbirthweightthrough improvingpregnantmothers’nutrientintakewouldbepolicy‐relevant. Inordertobringoutmoredetailedandsolidimplicationstopolicy,future researchneedstotestwhetherthefindingsofthispaperbasedonatwinsample canbegeneralizedtonon‐twinpopulations.Itisalsonecessarytoinvestigatefor whomincreasingbirthweightismosteffectiveinimprovingfuturelifechances,for instance,bydetectingatwhichpointinthebirthweightdistributiontheeffectof birthweightisstrongest. 13 Table1:SampleCollectedthroughWeb‐BasedSurvey MZTwins DZTwins Don’tKnow 2,742 (1,371pairs) 1,764 (882pairs) 214 (107pairs) (Source)Authors’calculations Table1‐a:DifferencesinEducationalOutcomesbetweenTwin‐Pairs Birthweights Privateprimary school Privatemiddle school Highestyearsof education Total MZTwins DZTwins 24.8% 21.0% 32.1% 5.9% 5.6% 6.5% 7.5% 7.1% 7.7% 38.4% 32.0% 48.8% Table1‐b:DifferencesinEducationalExpenditureonShadowEducationbetweenTwin‐Pairs Preschool Primaryschool Middleschool Highschool Total MZTwins DZTwins 2.4% 1.6% 3.2% 4.1% 3.1% 5.8% 6.2% 4.7% 9.0% 6.5% 4.6% 9.0% (Note)1.Shadoweducationrepresentsaccesstoprepschools,privatetutoring,anddistancelearning. 2.Privateprimaryandmiddleschoolsareincludingnationalschools. (Source)Authors’calculations 14 Table2:DescriptiveStatistics WholeSample DependentVariables: Birthweight Log(birthweight) Non‐LBW(1>2,500grams) IndependentVariables: Typeofjuniorhighschool(1=privateornational) Studentperformanceattheageof15 Rankingofcollegeattended Yearsofschooling Log(earnings) (Source)Authors’calculations 15 MZTwins Mean STDV Mean STDV 2,441.00 7.77 0.45 564.87 0.23 0.50 2413.76 7.76 0.50 551.51 0.23 0.50 0.171 2.57 52.00 14.38 5.96 0.376 1.10 9.84 2.33 0.74 0.16 2.60 51.72 14.42 5.98 0.37 1.08 9.76 2.30 0.74 Table3:GoodnessofFit Independent Dependent Birthweight Log(birthweight) Non‐LBW Private Middle School Student Performance (Age15) Ranking College Highest Yearsof Schooling Earnings 0.0060 0.0054 0.0075 0.0052 0.0070 0.0014 0.0061 0.0057 0.0194 0.0002 0.0001 0.0008 0.0013 0.0016 0.0006 (Source)Authors’calculations 16 Table4:EmpiricalResults(OLS) Independent Private Middle School Birthweight (/100) Log(birthweight) Non‐LBW Observations 0.011 (0.016) 0.016 (0.038) ‐0.001 (0.017) 1,998 Dependent Student Performance (Age15) 0.063* (0.032) 0.140* (0.079) 0.035 (0.035) 3,577 Ranking College Highest Yearsof Schooling Earnings 0.091 (0.442) 0.178 (1.082) 0.542 (0.517) 1,470 0.291*** (0.066) 0.810*** (0.167) 0.206** (0.070) 3,631 0.053*** (0.017) 0.122*** (0.043) 0.035* (0.019) 2,785 (Note)1.Thenumbersinparenthesesareheteroskedasticity‐robuststandarderrors. 2.***,**,and*represent1%,5%,and10%significancelevel,respectively. 3.Otherindependentvariablesare(a)privatemiddleschool:gender,father’seducation;(b)studentperformance:gender,father’seducation, livingstandardattheageofaround15;(c)rankingofcollege:thesamewith(b);(d)highestyearsofschooling:thesamewith(b);(e)log (earnings):age,agesquared,gender,father’seducation,livingstandardattheageofaround15,highestyearsofschooling,maritalstatus,years oftenureatthecurrentemployment,hoursofworkperday.Mostofthecontrolvariablesarestatisticallysignificant.Thefullresultsare availableuponrequest. (Source)Authors’calculations 17 Table5:EmpiricalResults(Twin‐FixedEffects) Independent Private Middle School Birthweight (/100) Log(birthweight) Non‐LBW Observations #oftwinpairs 0.050* (0.029) 0.112* (0.066) 0.053* (0.030) 1,257 (641) Dependent Student Performance (Age15) 0.210* (0.108) 0.575** (0.249) 0.099 (0.088) 2,206 (1,138) Ranking College 3.138 (3.090) 7.326 (7.149) 5.659* (3.055) 918 (736) Highest Yearsof Schooling ‐0.077 (0.170) ‐0.137 (0.417) ‐0.146 (0.162) 2,234 (1,144) (Note)1.Thenumbersinparenthesesareheteroskedasticity‐robuststandarderrorsandclusteringatthefamilylevel. 2.***,**,and*represent1%,5%,and10%significancelevel,respectively. (Source)Authors’calculations 18 Earnings 0.065 (0.071) 0.177 (0.161) ‐0.042 (0.072) 1,832 (1,032) Reference Almond,D.,Chay,K.Y.&Lee,D.S.(2005).Thecostsoflowbirthweight.Quarterly JournalofEconomics,120(3),1031‐1083. Black,S.E.,Devereux,P.J.&Salvanes,K.G.(2007).Fromthecradletothelabor market?Theeffectofbirthweightonadultoutcomes.QuarterlyJournalof Economics,122(1),409‐439. Behrman,J.R.&Rosenzweig,M.R.(2004).Returnstobirthweight.Reviewof EconomicsandStatistics,86(2),586‐601. Blickstein,I.&Kalish,R.B.(2003).Birthweightdiscordanceinmultiplepregnancy. TwinResearch,6(6),526‐531. Bound,J.&Solon,G.(1999).Doubletrouble:onthevalueoftwins‐based estimationofthereturntoschooling.EconomicsofEducationReview,18(2), 169‐182. Conley,D.&Bennett,N.G.(2000).IsBiologydestiny?birthweightandlifechances. AmericanSociologicalReview,65(3),458‐467. Currie,J.(2009).Healthy,wealthy,andwise:socioeconomicstatus,poorhealthin childhood,andhumancapitaldevelopment.JournalofEconomicLiterature, 47(1),87‐122. Currie,J.&Hyson,R.(1999).Istheimpactofhealthshockscushionedby socioeconomicstatus?thecaseoflowbirthweight.AmericanEconomic Review,89(2),245‐250. Kanjuku(2011).Zenkokukoukouchuugakuhensachisouran[Acomprehensivelist ofthedeviationvaluesofJapan’shigh‐andjuniorhighschools]. Kawaijuku(2011).Kawaijukuhensachiranking[Therankingofcolleges]. RetrievedFeb15,2013from http://daigaku.jyuken‐goukaku.com/nyuushi‐hensati‐ranking/kawaijyuku/ Kawaguchi,D.&Noguchi,H.(2012a).Shinseijinotaijuhanazegenshoshiteiru noka[Whyhasbirthweightdecreased?].Ihori,T.,Kaneko,Y.&Noguchi,H. eds.Aratanarisukutoshakaihosho:shogaiwotsujitashiensakunokochiku [Newrisksandsocialsecurity],UniversityofTokyoPress,17‐33. Kawaguchi,D.&Noguchi,H.(2012b).Teitaijyushussei:genintokiketsu[Thelow birthweight:thecauseandtheconsequence].GlobalCOEHi‐StatDiscussion PaperSeries,265. Kohara,M.&Ohtake,F.(2009).Kodomonokyouikuseikanoketteiyouin[The determinantsofeducationaloutcomesofachild].TheJapaneseJournalof 19 LabourStudies,588,67‐84. Lawlor,D.,Clark,H.,Smith,G.D.,&Leon,D.(2006).Intrauterinegrowthand intelligencewithinsiblingpairs:findingsfromtheAberdeenchildrenofthe 1950sCohort.Pediatrics,117(5),894‐902. Lin,M.&Liu,J.(2009).Dolowerbirthweightbabieshavelowergrades?:Twin FixedeffectandinstrumentalvariablemethodevidencefromTaiwan.Social Science&Medicine,68,1780‐1787. Linnet,K.M.,Wisborg,K.,Agerbo,E.,Secher,N.J.,Thomsen,P.H.&Henriksen,T.B. (2006).Gestationalage,birthweight,andtheriskofhyperkineticdisorder. ArchivesofDiseaseinChildhood,91(8),655‐660. Miller,P.,Mulvey,C.&Martin,N.(2005).Birthweightandschoolingandearnings: estimatesfromasampleoftwins,EconomicsLetters,86,387‐392. Nakamuro,M.&Tomohiko,I.(2012).Estimatingthereturnstoeducationusingthe sampleoftwins;thecaseofJapan.RIETIDiscussionPaperSeries,12‐E‐076. Neumark,D.(1999).Biasesintwinestimatesofthereturntoschooling.Economics ofEducationReview,18(2),143‐148. Oreopoulos,P.,Stabile,M.,Walld,L.&Roos,L.L.(2008).Short‐,medium‐,and long‐termconsequencesofpoorinfanthealth:ananalysisusingsiblingsand twins.JournalofHumanResources,43(1),88‐138. Petronis,A.(2010).Epigeneticsasaunifyingprincipleintheaetiologyofcomplex traitsanddiseases.Nature,465,721‐777. Tsukamoto,H.,Fukuoka,H.,Koyasu,M.,Nagai,Y.&Takimoto,H.(2007).Risk factorsforsmallforgestationalage.PediatricsInternational,49(6),985‐990. Royer,H.(2009).Separatedatgirth:U.S.twinestimatesoftheeffectsofbirth weight,AppliedEconomics,1(1),49‐85. 20