Document 13997691

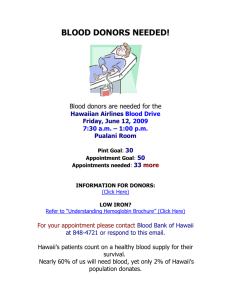

advertisement