Document 13997656

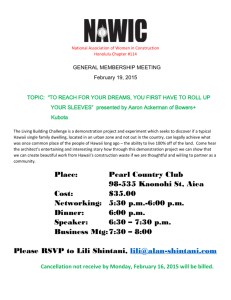

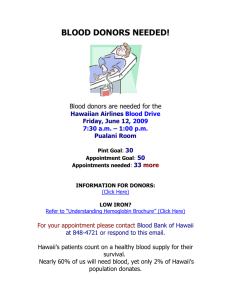

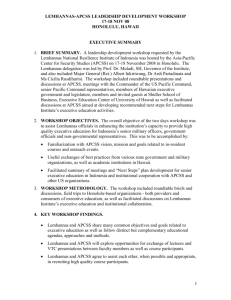

advertisement