University of Hawai`i at Mānoa Department of Economics Working Paper Series

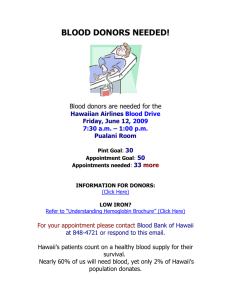

advertisement