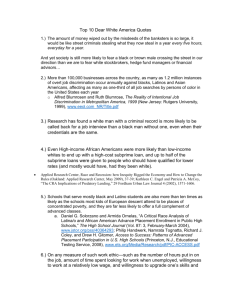

The Kerner Commission Plus Four Decades:

advertisement