Pretend Play Skills and the Child's Theory of Mind

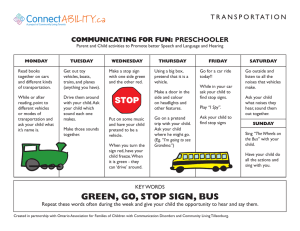

advertisement