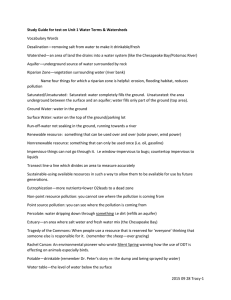

Socioeconomic Value of the Chesapeake Bay Watershed in Delaware March 2011

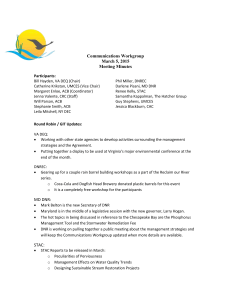

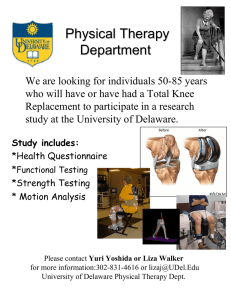

advertisement