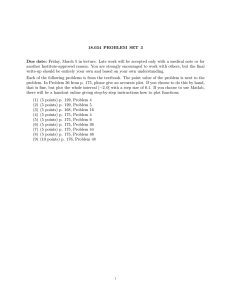

MatLab Help Notes

advertisement

MatLab Help Notes

MatLab is a powerful computer language for specialized calculations in engineering and

other technical areas. MatLab is similar in structure to other programming languages and

is most closely related in syntax to the c language. Its great strength is that it is easily

extended so that a user can purchase or create library functions to tailor the language to a

particular discipline. MatLab is available in two forms. The student edition (currently V

6.5, Release 13) comes with the Symbolic Math Toolbox and Simulink. (Toolbox is

MatLab's name for library). The professional edition is available on the computer

network in the labs and it includes the professional edition of the signal processing

toolbox, the controls toolbox, and the symbolic math processor. The student version cost

about $100 dollars but it is not a stripped down version. It can do everything the

professional version can do. What's missing from the student version is the wide array of

toolboxes. Additional toolboxes can be purchased for about $30 dollars each and include

such things as the Signal Processing Toolbox and the Controls Toolbox which are useful

in such courses as EE 310, 311, and 360.

MatLab opens with a screen similar to that shown in Figure 1 below. The three windows

are called the Launch Pad, Command History, and the Command Window.

Figure 1

MatLab's command window and opening screen.

The Launch Pad provides access to certain tools and documentation. The Command

History window has a complete history of all of the commands that are typed into the

command window including a date and time stamp (in green). You can page back

through the history and copy commands or double click on any command in the history

window to run it again. The Command Window is the main operating window. You use

it by typing in commands which Matlab executes when you push Enter.

1

The command window is very much like a sophisticated calculator. You may enter

equations and assign values to variables. These are remembered as you proceed down the

sheet. All commands terminate with either a semicolon or the enter key. If you omit the

semicolon, MatLab automatically prints the result of that command to the screen. Thus,

entering 5 + 6; does nothing. But entering 5 + 6 produces the answer 11.

But Matlab is much more than a calculator. It also provides a sophisticated programming

language that lets you enter, edit, and run full programs. These are done in m-files. An

m-file is just a text file that contains a list of instructions similar to what you might type

into the command window. The instructions can have loops, if statements, and functions

and the syntax is very similar to that of a programmable calculator.

For simple calculator-like use you can open Matlab and type in the equations. For

example, if I want to find the arc tangent of 0.5 in degrees, I would enter the following:

>> atan(.5)*180/pi

ans =

26.5651

Since all angles are in radians, I multiply by 180o per Pi radians to convert to degrees.

Matlab provides an answer to four decimal places. To get more accuracy in my result I

change the format with a format statement like this:

>> format long

>> atan(.5)*180/pi

ans =

26.56505117707799

To write a program as an m-file, I first need to tell Matlab where to store the program. If

you don't do this Matlab stores the program in a default directory. You can change your

default directory in several ways. The quickest way is to just enter the new path as a

change directory command in the command window as you would if you were using

DOS. For example,

>> cd c:\courses\ee210

changes the default directory to ee210 under courses on my c: drive. (Other DOS

commands work in the command window as well.) If you don't remember DOS

commands, you can change the current directory with a mouse by clicking on the Browse

button on the current directory list at the top center of the screen. You can also change

the directory by selecting the current directory tab in the Command History window and

browse for a directory there.

After you have a directory established you can create a new m-file by selecting

FileNewM-File from the file menu. Matlab then opens an editor and you are ready

to enter your program. The editor window looks like that shown in Figure 2.

2

Figure 2

The editor window. To open the editor select FileNewM-File from the file menu.

Note that we have not yet named our M-File or saved it. For a simple example enter the

following five lines into your open edit window.

%Test.m

x = 3;

y = 92;

z = x^4 - y^2 + 12;

disp(z);

The first line begins with a % sign so it is a comment and is otherwise ignored by the

program. The next three lines create three new variables and assign them values. The

last line displays the value of z. Note that we could have displayed the value of z simply

by omitting the semicolon at the end of the equation for z.

Save your m-file as Test.m and return to the Command Window by selecting it at the

bottom of the screen. In the command window type test to get the result shown below.

>> test

-8371

3

Since Test is the name of an m-file in your directory it becomes the name of a command

which can be executed from the command window. Typing the word test causes Matlab

to execute the commands saved in the m-file.

Learning Matlab is a matter of learning the syntax of the language. The language itself is

all command line driven but with a few hours of practice on some examples you can

become relatively proficient. What follows is a list of the more common commands and

some examples of how they might be used in a circuits class.

Getting Help

Matlab's help can be frustrating until you learn a few basic commands. But Matlab

provides detailed help on every function and in many cases provides an example of how

the function is used. For example, if I want to know how the roots function is used I enter

the following:

>> help roots

Matlab produces the following lines.

ROOTS Find polynomial roots.

ROOTS(C) computes the roots of the polynomial whose coefficients

are the elements of the vector C. If C has N+1 components,

the polynomial is C(1)*X^N + ... + C(N)*X + C(N+1).

See also POLY, RESIDUE, FZERO.

The difficulty is that many times you think there ought to be a function but you don't

know its name so you don't know what to ask for help about. When this happens enter

helpwin. The helpwin command provides a hypertext linked help document that allows

you to see all of the functions by category. Enter helpwin into the command window to

get the screen shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Enter helpwin to get this screen. Click on any topic in blue for additional information on

that topic. For example click on Elfun to get a list of all of Matlab's elementary math

functions.

4

One other command is useful when you need help. That's the lookfor command. This

command searches through all of the m-files and functions looking for a keyword. For

example lookfor roots produces the following display.

>> lookfor roots

POLY Convert roots to polynomial.

ROOTS Find polynomial roots.

GFROOTS Find roots of a polynomial over a prime Galois field.

RLOCFIND Find root locus gains for a given set of roots.

MROOTS Polynomial roots with multiplicity estimate

vroots.m: % function out = vroots(mat)

FILTCON Returns roots for DFILDEMO.

FILTFUN Returns frequency response and roots for DFILDEMO.

FILTFUN2 Return frequency response norm and roots for DFILDEMO.

POLYSCALE Scale roots of polynomial.

RLOCFIND Find root locus gains for a given set of roots.

RLOCFIND Find root locus gains for a given set of roots.

You can then follow this up with a help on one of the listed commands for more detailed

help. The lookfor command is somewhat of a last resort since it searches all of the mfiles and takes several minutes (or longer) to complete. You can cancel it in mid-flight by

entering Control-C.

Editing and Screen Ops:

Here is a list of the more common editing and screen operators and a brief description

of what they do.

quit - exits MatLab. You can also exit from the file menu. exit works as well.

variable names - Variables start with a letter and may be up to 19 characters long.

After the first letter you can use letters, numbers, and underscore. MatLab is

CASE sensitive - nt is a different variable than nT. Note that m-file names are

NOT case sensitive so Test is the same as test.

clear - clear by itself clears ALL variables (without asking). clear x clears only the

value of x.

comments - All text after a % sign is a comment.

; - A semicolon at the end of a line suppresses printing of the results of that line. If

you forget the semicolon your screen rapidly fills up with results you don‟t want.

Multiple commands can be placed on one line if they are separated by a

semicolon.

: - A colon is used to create arrays, address a matrix, or specify iterations. Here are

some examples:

j:k is the same as [j, j+1, ..., k]

j:i:k is the same as [j, j+i, ..., k]

A(:,j) is the jth column of A (read this as all rows in column j)

A(i,:) is the ith row of A (read this as all columns of row i)

A(j:k) is A(j), A(j+1), ... , A(k)

... - Exactly three dots at the end of a line allows you to continue on the next line.

5

who - This command produces a list of variable names that you have used in the

current session. Type the name of the variable to get its value. You can also type

whos to get the variables listed in a long form with more information.

editing -Use the cursor keys (, , , and ) for editing. Push once to see the

previous command or gets the next command (if there was one). Once you have

a command listed you can edit it using and plus the backspace and delete

key. Push enter to re-evaluate the command. You can likewise use the mouse to

scroll backward through the window to view commands that have rolled off the

screen.

save filename - This command saves the current workspace. You should normally

use the .mat extension as in Myfile.mat.

load filename - This command loads a file saved with the save command to restore a

previously saved workspace.

what - Produces a listing of m files, mat files, and mex files in the current directory.

lookfor- searches through help files for a keyword. This is more useful than help

topic since you don‟t have to know the topic name that MatLab uses. The syntax

is:

lookfor keyword

For example, lookfor filter, produces 21 entries from which you can ask for syntax

help.

format - using the format command sets the format of the numbers and results

MatLab displays. (The internal representation remains unchanged). The

following are the most useful format commands:

format

format

format

format

format

compact

long

short

short e

hex

Reduces line spacing in the command window

16 digits

6 digits (the default)

6 digits with exponent

hexadecimal

M Files

The real power of MatLab comes from the ability to create programs which can be

saved and executed from the command window. MatLab programs are called m-files.

To write an m-file you should first change MatLab's directory to the disk location

where you want to store the m-file. Use the cd command to change the directory from

the command window. If you want to know what directory you are in use the pwd

command.

M files are also referred to as “script files”. An m-file is a text file that contains

statements executable by MatLab. M-files are stored on your computers disk and

have a name of the form “filename.m”. They are executed in MatLab by typing the

filename (without the extension) at the MatLab prompt in the command window.

Execution of an m-file produces the same results as if you had typed the information

in one line at a time. M-files represent a very powerful way to extend the MatLab

command language.

6

M File Manipulation:

dir - This is the same as the DOS command for directory. ls works as well.

cd - This is the same as the DOS command for change directory.

type filename - looks for the file called filename.m in the current directory and

displays it in the command window.

delete filename - deletes filename.m in the current directory.

pwd - same as the UNIX command for print working directory. Typing cd alone

(without a path) produces the same result in MatLab.

which filename - displays the path to filename.m

Creating M Files:

You can create an m-file using any word processor or editor that will create a text

(ascii) file with a .m extension. In DOS it is convenient to use EDIT but a full

word processor offers more text manipulation options. MatLab has it‟s own built

in editor which you can invoke from the file menu in the command window.

From the File menu in the command window select new m-file. You will see the

following screen shown in Figure 2. This is MatLab's m-file editor.

Here is an example of an m-file named Sineplot which produces a plot of sin(x)

and cos(x) using the plot function. Because MatLab is somewhat arcane in its

syntax, m-files should be fully commented.

% TITLE: Sineplot.m

%

% This m file creates a plot of sin(x) and cos(x) using

%

the plot function.

%

x = (-4*pi:pi/100:4*pi); % x goes from -4Pi to 4Pi

y1 = sin(x);

% y1 is the sin(x)

y2 = cos(x);

% y2 is the cos(x)

figure(1);

% Select figure 1

clf;

% Clear the figure

plot(x,y1,'blue');

% Plot sin(x) in blue

hold on;

% keep it from being erased

plot(x,y2,'red');

% Plot cos(x) in red

Figure 4

An example MatLab m-file which creates a plot of sin(x) and cos(x) for x going

from -4 to +4

You may type in the program in Figure 4 using MatLab's editor. Save the file

under the name sineplot.m. Return to the command window and run the

program by typing sineplot. If all goes well you should get the results shown

in Figure 5 below.

7

Figure 5

The results of running the program called sineplot shown in Figure 4.

Matrix (Array) Ops and Definition

Array - MatLab commonly uses the word Array to mean a one dimensional matrix.

When an array has more than one dimension it is referred to as a matrix.

Addressing an array x(3) is the third element of x.

x(1:3) is elements 1, 2, and 3 of array x.

x(1:2:4) is elements 1 and 3. In this notation 1 is the starting value, 2 is the step

size, and 4 is the last value - x(Start:Step:End).

Creating an array - MatLab does not contain a dimension statement or any other

explicit way to declare a variable and its size. Variables are dimensioned as

needed. This sometimes causes problems when a matrix used in one part of a

program needs to be made larger in a second part. You can get around this by

creating and sizing a vector at the outset by using the zeros command.

zeros - This command produces zeros an assigns them to a variable or an array.

The syntax is

x = zeros(size);

where size is the dimensions of x. For example x = zeros(3,5); creates x

as having 3 rows and 5 columns and initializes them to zero.

ones - This command is the same as the zeros command except that it produces

arrays of ones.

Array Creation Examples

Create an array, x, with four elements. Note the use of the square bracket [ ].

x = [1 2 3 4];

x is a 1 x 4 row matrix. To create a column matrix write:

8

x = [1;2;3;4]; or x = (1;2;3;4);

or, use the transpose operator (see below).

Create a second array, y, where each element is the square root of the elements

in x array.

y = sqrt(x);

Create a third array, z, where each element is 2 times the element in x.

z = 2*x;

Create an array using colon notation. In this example x is an array having

elements 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10. The format is x(Start, Step, End). If

you leave out the step value, it defaults to 1.

x = [0:2:10];

Create an array by combining two other arrays. In this example A has three

elements and B has 4 elements. A new array, C, is made by combining A

and B. In combining two arrays you use [ ].

A = (1:3); B = (4:7);

C = [A B];

C will consist of elements 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Create an array using the linspace or logspace commands. These operators

creates a linear or log space between two specified end points. The syntax

is:

x = linspace(start, last, number);

x = logspace(start, last, number);

Matrix Arithmetic

Addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division are defined in two ways for

arrays and matrices. The operators normally used (+, -, *, and /) are defined as

they usually are for matrices (division of two matrices is defined as

multiplication by the inverse). The operators of multiplication and division

are also defined using the dot notation (.*, and ./) to mean that the operations

are to be performed on an element by element basis.

Operations between a scalar and an array are done to every element in the array.

For example C = A - 2; will subtract 2 from every element in A and make

the new matrix C.

Transpose - use the .' operator. For example if B is a row matrix (say 1 x 5) then

writing C = B.' would make C a column matrix (5 x 1). The dot apostrophe

is necessary for a transpose. Using the apostrophe alone does a complex

conjugate transpose.

Solving Simultaneous Equations

MatLab makes solving simultaneous linear equations very easy since it is very good at

manipulating matrix equations. Consider the set of equations given below.

x1 3x2 3x3 7

2 x1 6 x3 13

4 x2 5 x3 12

In these three equations, x1, x2, and x3 are unknown. We can rewrite these equations

in matrix form as A x b

9

where the three matrices A, x, and b are given by

1 3 3

7

x1

A 2 0 6

b 13

x x2

0 4 5

12

x3

Since Matrix division is not defined we solve the matrix equation for x as

1

x A b where the term A1 is defined as the matrix inverse of A.

Thus, to solve these three equations, we need only find the inverse of the A matrix

and multiply it times the b matrix. In MatLab we write the following three lines.

A = [1,3,3;2,0,-6;0,4,5];

b = [7;-13;12];

x = A^(-1)*b

Leaving the semicolon off of the last line causes MatLab to print the value of x as

x=

-0.5000

0.5000

2.0000

Output and Input

Printed output:

To print the value of any variable in the workspace. simply type the variable name

followed by the enter key. You can use format compact to get a neater

display. The result of any equation in the workspace or in an m-file will be

printed to the screen if you leave off the semicolon at the end of the line.

disp – display. This is the same as leaving the semicolon off of an expression. It

allows a little more clarity in programs.

fprintf - prints formatted data to a file or to the screen. The syntax is

fprintf(fid, 'format string', arg1, arg2, ... );

The format string contains conversion characters that determine how the output is

printed. Each conversion character must be preceded by a percent sign (%).

Adding a \n to the format string produces a new line. The common conversion

characters are:

c

single character

d

signed integer

e

floating point with an exponent

f

floating point without an exponent

g

general format. Uses e or f as needed.

i

signed integer

o

octal integer

s

string

u

unsigned integer

x

hexadecimal integer

10

The term fid is a file identifier. If fid = 1 the output is sent to the screen.

This is similar to the command for formatted output in C (printf). Here are

few examples.

i = 13; j = -45; r

= 39.567; s = 5.4136789;

Print Command fprintf(...)

Printed output

(1, '%6.3f\n', r, s);

39.567

5.414

r =39.56700000 s = 5.4137

r = 39.567 s = 5.41368

i = 13 j = -45

i =

13 j =

-45

i = d

Hello Mom!

(1,

(1,

(1,

(1,

(1,

(1,

'r =%2.8f s = %3.4f\n', r, s);

'r = %g s = %g\n', r, s);

'i = %i j = %i\n', i, j);

'i = %5i j = %5i\n', i, j);

'i = %x\n', i);

'Hello Mom!\n');

File Output:

Sending data to a file is the same as sending it to the monitor except that the fid

is changed to match the file instead of the screen. If fid = 1 the fprintf

command sends data to the screen. To find the fid for a file use

fid = fopen('filename');

save - The save command saves the workspace variables to a file. If no variables

and no file name is specified in the command the entire workspace is saved to

a default file named matlab.mat. All data is saved in a binary format. You

can use a -ascii option to save data in an ascii format. Here is an example.

save 'c:\dsp97\myfile.txt' r s -ascii -double

This command saves the variables r and s in double precision ascii format in a

file called myfile.txt The variables can be restored with the load command.

Keyboard Input:

input - allows input from the keyboard. You can enter a single value or a matrix

of values which are assigned to a single variable. All variables come in as

numeric data unless a string argument is given in which case the data comes in

as a string. For example

x = input('Enter a value for x ');

will produce a prompt for x. You may then enter a single number or a vector

such as [2 3 4 5] which will be assigned to x.

To get x in as a string of characters write input like this.

x = input('Do you like jello? ', 's');

In this case the user would type a response such as yes or no and x would

become a string corresponding to the answer.

ginput - allows input from the mouse or trackball. The format is

[x y]=ginput(n);

The vector [x y] is returned as the coordinates of the point where the mouse

was clicked. The variable n is the number of points that will be accepted.

Thus [x y] = ginput(1); returns a single point.

11

File Input:

fread - reads binary data from a file. The format is

D = fread(fid);

In this case D is a matrix where the data from the file is stored. The file is the

file which has the file identifier given by fid. To find the fid for a specific file

use fid = fopen('myfile.mat'); where myfile.mat is the file name of a

file holding binary data (possibly created using the save command.

load - the load command is the counterpart to the save command. If the load

command is used alone it loads all of the variables in the file called

matlab.mat into the current workspace. You can also use load filename.ext.

For example, if myfile.txt has data previously saved by the save command

you would type

load 'myfile.txt';

Graphs:

plot - creates a 2-D graph. The normal syntax for this command is

plot(x,y);

where x and y may be matrices or functions. If x and y are both matrices then

it takes corresponding elements as the ordered pairs to make the plot. for

example:

x = (0: pi/100: 4*pi);

y = sin(x);

plot (x,y);

produces a plot of sin(x) for x going from 0 to 4 in increments of /100.

If you use plot(x) alone you get a plot of the values of x versus the array

element number. If x is complex it plots the real part against the imaginary

part. Plot has a number of options to modify the color and line style. See

"Plot Options".

semilogx, semilogy, and loglog - These are the same as the plot command with

the same syntax. They produce log (base 10) plots on either the x, y, or both

axes.

stem - creates a stem plot. This is supposed to be a plot of discrete data with the

options of the plot function (above). The syntax is:

stem(x,y);

where x and y are matrix functions. A stem plot is a sequence of lines from

the y value to the x axis. The color and line style are the same for stem as they

are for plot (see "Plot Options"). You can get multiple plots on the same axis

by using the hold function (see hold on). If there are too many points, the

graph has an awkward appearance. You can create your own stem plot using

the line function. An example of a stem plot using the line command is

given under the discussion on m files.

freqs - plots a transfer function in the S domain. The syntax is

12

freqs(num,den);

or

h = freqs(num,den, w);

where num and den are the numerator and denominator vectors for a transfer

function in s. For example, if the transfer function is given by

4s 2 2s.5

H (s) 3

.5s 3s 2 5s 1

we could obtain a plot of the magnitude versus frequency using the following

commands:

num =[4 2 .5]; den = [.5 3 5 1];

f = linspace(0, 1000);

w = w*pi*f;

% w is in radians.

H = freqs(num, den, w);

% H is a complex frequency vector.

plot(f, abs(H), 'k');

axis([0 1000 0 1.5]);

impulse - This function is in the control systems toolbox and finds the impulse

response for either a discrete time system or a continuous time system. The

syntax is:

sys = tf(num, den, T);

impulse(sys, Ti:T:Tf);

or,

sys = tf(num, den, T);

[h nT] = impulse(sys, Ti:T:Tf);

where num and den are the numerator and denominator polynomials in z, T is

the sample time in seconds, Ti is the starting time for the plot, Tf is the ending

time for the plot, h is the impulse response vector, and nT is the time vector.

The tf() function creates a system vector from num, den, and T. Since a

sample period is specified, the system created is discrete. If this function is

omitted, the impulse function assumes the system is in the s domain.

step - This function is in the control systems toolbox and finds the step response

for either a discrete time system or a continuous time system. (This function

replaces the function dstep which is no longer supported.) The syntax is:

sys = tf(num, den, T);

step(sys, Ti:T:Tf);

or,

sys = tf(num, den, Ti:T:Tf);

[s nT] = step(sys, T);

where num and den are the numerator and denominator polynomials in z, T is

the sample time in seconds, Ti is the starting time for the plot, Tf is the ending

time for the plot, s is the step response vector, and nT is the time vector. The

tf() function creates a system vector from num, den, and T. Since a sample

period is specified, the system created is discrete. If this function is omitted,

the step function assumes the system is in the s domain.

Multiple plots - To get more than one plot on an axis you can string vectors

together inside the plot argument. For example

x = (0 : pi/100 : 4*pi);

13

plot(x, sin(x), x, cos(x));

produces a plot of x vs sin(x) and x vs cos(x) in two different colors for x

from 0 to 4 in steps of /100.

hold - holds the current plot so that the next plot function is plotted without

erasing the first plot. You can use hold alone to toggle the hold function

or you can use hold on or hold off.

Plot Options color and form - You can get various line types and colors by adding a string

option to the plot arguments. The syntax is

plot (x, y, S);

where S is a string (1, 2, or 3 characters long) created with single quotes as

in Basic. Here is a table of the options.

Color

Form

b –blue

c – cyan

g - green

k - black

m - magenta

r – red

w- white

y - yellow

. point

o circle

x

+

- solid

*

: dotted

-. dash dot

_ dash

For example

plot(x, sin(x), ‘k.’);

produces a plot of x vs sin(x) in black made out of dots. You may also

spell out the color name for clarity, e.g. 'black' or 'blue'.

whitebg - this function changes the figure background color (not

necessarily to white. The syntax is:

whitebg;

- the name alone toggles the background color between

white and black.

whitebg(c)

- sets the background to a specific color where c is a letter

form the table above as a string. For example to get a blue background

you would type:

whitebg('b');

grid - adds grid lines to an existing plot. If they are already on the plot

then grid toggles them off.

axis - This command lets you scale the x and y axis after the plot has been

completed. The syntax is:

axis([Xmin

Xmax

Ymin

14

Ymax]);

Notice the confusing requirement for both parentheses and brackets in

this command.

title - adds a title to the existing graph. The format is:

title('THIS IS A TITLE');

The title gets printed centered at the top of your graph.

xlabel and ylabel - add labels to the x and y axis. The format is similar to

title.

text - allows the user to add text information to a figure at a specified

coordinate. The syntax is:

text(x, y, ‘text’);

where (x, y) is the lower left corner of the text block and „text‟ is the

text added.

clf - clears the current figure.

print - sends the current figure to the default printer. This command has

numerous options that allow you to change the printer or print to the

Windows clipboard. See orient to change the paper orientation.

orient - allows you to change the orientation of the paper from portrait to

landscape for printed output. The syntax is:

orient portrait;

or

orient landscape;

orient by itself returns the current orientation.

subplot (m, n, p) - divides the figure into m rows and n columns for

subplots. p is the number of the subplot that is current. For example,

subplot(2,2,1)

creates two rows and two columns for four subplots. It makes the top

left current. The following creates two graphs with y = sin(x) on the

top half and z = cos(x) on the bottom half.

clear

subplot(2,1,1);

x=(0:pi/100:4*pi);

/100

y=sin(x);

plot(x,y);

subplot(2,1,2);

z=cos(2*x);

plot(x,z);

% 2 rows - 1 column

% x goes from 0 to 4 in steps of

% plots sin(x) in top subplot

% makes the bottom subplot current

% plots cos(2x) in the bottom subplot

15

Special Functions:

fourier - operates on symbolic data and completes the Fourier transform which is

defined as:

jt

f (t ) e

F ( )

dt

The syntax for the Fourier transform is:

y = 'exp(-t)*sin(t)'

%y must be given as a symbolic function.

F = fourier(y);

%assumes that y is a function of t and makes F

%

a function of w.

or,

F = fourier(y, ‘v’, ‘x’)

% Takes y to be a function of x instead

%

of t and makes F a function of v

%

instead of w.

You can also use the int function to directly evaluate the symbolic form of the

Fourier integral.

invfourier - operates on symbolic data to complete the inverse Fourier transform

which is defined as:

1

jt

f (t )

F ( ) e d

2

The syntax for the inverse Fourier transform is:

F = '1/(j*w + 2)';

f = invfourier(F)

% F must be in symbolic form.

% assumes F is a function of w and makes f a

%

a function of t.

or,

f = invfourier(F, ‘x’, ‘v’) % Takes F to be a function of v and

%

makes f a function of x.

laplace- operates on symbolic data and completes the LaPlace transform which is

defined as:

st

F ( s) f ( t ) e dt

0

16

The syntax for the LaPlace transform is:

y = 'exp(-t)*sin(t)' %y must be given as a symbolic function.

F = laplace(y);

%assumes that y is a function of t and makes F

%

a function of s.

or,

F = laplace(y, ‘v’, ‘x’)

% Takes y to be a function of x instead

%

of t and makes F a function of v

%

instead of s.

You can also use the int function to directly evaluate the symbolic form of the

LaPlace integral.

invlaplace - operates on symbolic data to complete the inverse LaPlace transform

which is defined as:

c j

1

st

f (t )

F ( s) e ds

2j c j

The syntax for the inverse LaPlace transform is:

F = '2/(s^2+4)';

f = invlaplace(F)

% F must be in symbolic form.

% assumes F is a function of s and makes f a

%

a function of t.

or,

f = invlaplace(F, ‘x’, ‘v’) % Takes F to be a function of v and

% makes f a function of x.

fft - Completes the discrete Fourier transform (DFT) on numeric data. The DFT is

defined as:

N 1

F ( k ) f ( n) e

j

2kn

N

n 0

The syntax for the FFT is:

x = [1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0];

F = fft(x)

or,

F = fft(x, N) %In this case an N point DFT is done. If x has

% fewer than N elements it is padded with zeros.

% If it has less than N elements it is truncated to

% N elements.

Note that if x has N elements where N is a power of 2 the fft computes the DFT

using the algorithm for the fast Fourier transform. If N is not a power of 2 then a

slower non-power-of-two algorithm is used.

ifft -- Completes the inverse discrete Fourier transform (IDFT) on numeric data. The

IDFT is defined as:

2kn

1 N 1

j

F ( k ) f ( n) e N

N k 0

The syntax for the IFFT is:

F = [1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0];

x = ifft(F);

or,

x = ifft(F, N) %In this case an N point DFT is done. If x has

% fewer than N elements it is padded with zeros.

17

%If it has less than N elements it is truncated to

% N elements.

Note that if F has N elements where N is a power of 2 the ifft computes the IDFT

using the algorithm for the inverse fast Fourier transform. If N is not a power of 2

then a slower non-power-of-two algorithm is used.

int - completes a definite or indefinite integral on symbolic data. The syntax for the

integrate function is:

a = int(s)

% symbolic indefinite integral of s with respect to

%

its symbolic variable.

or,

a = int(s, ‘v’)

or,

a = int(s, b, c)

or,

% symbolic indefinite integral of s with respect

%

to v.

% definite integral from limits b to c.

a = int(s, ‘v’, b, c)

% definite integral from b to c with

%respect to variable v.

diff - this function calculates either the derivative (if the argument is symbolic) or

it calculates successive differences (if the argument is a numeric array).

For differentiation of a symbolic argument there are four forms:

diff(s);

%symbolic derivative with respect to x.

or

diff(s, ‘v’);

% symbolic derivative with respect to v.

or

diff(s, 2);

% second derivative

or

diff(s, ‘v’, 2);

% second derivative with respect to v.

In all of the above forms s MUST be symbolic.

If the argument is an array then diff calculates the difference between

successive elements of the array. For example:

x = [1 2 4 7];

a = diff(x);

produces

a = [1

2

3]

conv - performs the convolution summation on two arguments which are arrays.

For example if a, b, and c are arrays then:

c = conv(a, b);

N

evaluates c according to c( k ) a( j ) b( k 1 j )

j 1

This is numerically equivalent to multiplying two polynomials whose

coefficients are in a and b.

18

deconv - this is the deconvolution operation which deconvolves the vector b out of

vector a. The syntax is:

[Q R] = deconv(a, b);

In this case a = conv(b,Q)

and R is a remainder. This is numerically equivalent

to division if a and b are vectors of polynomial coefficients.

rand - This function produces a set of uniformly distributed random numbers over

the interval 0 to 1. There are numerous options. The most useful are:

rand;

- produces a single number on the interval 0 to 1

rand(m,n); - produces a m x n array of numbers.

rand(‘seed’,n); - sets the seed for the random number generator to n.

randn - This function is the same as rand except that the numbers generated

follow a normal distribution.

residue - This function finds the residues, poles, and the direct term for a partial

fraction expansion. The syntax is:

[r p k] = residue(num, den);

or,

[num den] = residue(r,p,k);

where r is a vector of the residues, p is a pole vector, and k contains the direct

term. Thus, for an nth order polynomial in s that has no repeated roots, we can

write

num( s)

r (1)

r (2)

r ( n)

k ( s)

den( s) s p(1) s p(2)

s p ( n)

Note that r and p are column vectors and k is a row vector.

In the case where the polynomial has a repeated root, p(j) the expansion into

partial fractions contains a term of the following form:

r( j)

r ( j 1)

r ( j m 1)

2

s p( j ) ( s p( j ))

( s p( j ))m

where m is the number of times the root is repeated.

The syntax [num den] = residue(r,p,k); reverses the residue operation to

reform polynomials.

roots - This function finds the roots of a polynomial. The syntax is:

r = roots(p);

where p is an array containing the coefficients of the polynomial in

descending order. For example, the polynomial k1x 3 k 2 x 2 k3 x k 4 0

could be represented as p = [k1 k2 k3 k4]. In this case, since p is a row

vector r will be a column vector. If p is a column vector, r will be a row

vector.

Programming like functions:

19

LOOPS:

FOR - This is similar to the FOR/NEXT loop in Basic except for slight deviations

in the syntax. The general syntax is:

for i=start:step:last

loop body

end

If the step value is omitted it is assumed to be 1. For loops may be nested as

needed.

WHILE - The general syntax for the WHILE loop is:

Initialize expression variable

while expression

loop body

end

As in Basic the loop body MUST modify the value of the expression variable

or the loop runs forever.

IF Statements:

The IF statement is the same as in Basic except the word “then” is not used and it

is terminated with end instead of endif. There are several forms for the IF.

if expression

statements executed if TRUE

end

if expression

statements executed if TRUE

else

statements executed if FALSE

end

if expr1

statements executed if expr1 TRUE

elseif expr2

statements executed if expr1 is FALSE AND expr2 is TRUE

elseif expr3

statements executed if expr2 is FALSE AND expr3 is TRUE

elseif ...

...

end

Conditional Operations or IF:

The conditional ops for the if statement are:

== Equal to

< Less than

> Greater than

<= Less than or equal

>= Greater than or equal

~= Not equal

20

Note that for those unfamiliar with the conditional operations in C and C++

the logical equals in MatLab (==) is a source of hard to find errors in

programs.

Here is an example of an IF nested inside a FOR. This example creates an

array x(100) where the first 10 values are 1 and the last 90 are 0.

for k = 1:100

if k < 11

x(k) = 1;

else

x(k) = 0;

end

end

21

Example 1 – Nodal Analysis1

Use nodal analysis and Matlab to determine the node voltages in the following circuit.

Figure E1-1

Find the node voltages V1 and V2.

At node 1 we get

v1 v2 v1

4

2

This equation can be written as 3v1 v2 20

i1 i2 i3

or 5

Similarly at note 2 we get

v v

v

i2 i4 i1 i5 or 1 2 10 5 2

4

6

This equation can be written as 3v1 5v2 60

Thus we have two equations and two unknows. Putting these two in matrix form we can

3 1 v1 20

write

3 5 v2 60

This matrix equation is in the form of A x b where

v

3 1

20

A

, x 1 , and b

3 5

60

v 2

1

1

The solution to this matrix equation is x A b where A designates the inverse A

matrix.

In Matlab, the A matrix would be entered in the following form:

A = [3 -1; -3 5];

In Matlab matrices are entered by rows with semicolons to indicate the next row break.

The following m-file produces the answer.

1

This example is taken from Fundamentals of Electric Circuits, 2nd edition by Alexander and Sadiku, p. 80.

22

%Example1.m

A = [3 -1;-3 5];

b = [20 ; 60];

x = A^-1*b;

disp(x);

Figure E1-2

An m-file named Example1.m which diplays the result for this example.

The m-file is saved as Example1.m. From the command window we run the m-file to get

the following result.

>> example1

13.3333

20.0000

23

Example 2 – RC Transient Plot

Use Matlab to plot the capacitor voltage and current for the circuit shown in Figure E2-1

below.

Figure E2-1

An RC circuit with a step input.

We assume that the capacitor is completely discharged for t < 0. When the switch closes,

the voltage across the capacitor is given by vc 12(1 e t /(RC ) ) . Likewise, the capacitor

dv

current is given by ic C c (12 / R)e t /( RC ) .

dt

Solution using loops

To create a plot in Matlab we evaluate these two equations in an m-file for a range of

values of time and plot the result. Matlab provides for several plot options and there are

several ways to arrange the program itself. Since you are familiar with the C

programming language the most obvious solution would be to write a simple for loop to

evaluate the equations. Figure E2-2 shows an m-file which does this.

%Example2.m

R = 1000;

%set the value of R and C as 1k and 1uf

C = 1e-6;

t = 0:.0001:.01;

%t is a vector from 0 to .01 in steps of .0001

%Use a loop to evaluate the voltage and current equations

for i=1:length(t);

vc(i) = 12*(1-exp(-t(i)/(R*C)));

ic(i) = 12*exp(-t(i)/(R*C));

end

figure(1);clf;

%Assign a figure number and clear figure

plot(t, vc);

%plot time vs capacitor voltage

title('Capacitor voltage');

%Create a title for this graph

xlabel('Time');

%label the x axis

ylabel('Volts');

%label the y axis

figure(2);clf;

%A second figure for the current

plot(t, ic);

%plot time vs capacitor current on fig 2

title('Capacitor current');

%add titles and axis labels.

xlabel('Time');

ylabel('milliamps');

Figure E2-2

An m-file named Example2.m which uses a for loop to evaluate and plot the capacitor

voltage and current against time in two different figures.

24

Note that the line t = 0:.0001:.01; creates an array named t which has 101 values

ranging from 0 to .0001 in steps of .01. Also note that in Matlab no variables need to be

declared before they are used. Even arrays can be used without declaring them or

assigning them a dimension. On occasion it is necessary to declare an array and give it a

size and you can use the zeros functions to do this, but for the most part, Matlab is able to

figure out the variable type and array size from the context in which the variable is used.

The loop given by

for i=1:length(t);

vc(i) = 12*(1-exp(-t(i)/(R*C)));

ic(i) = 12*exp(-t(i)/(R*C));

end

is a standard for loop structure which creates two new arrays called vc and ic. It fills

these arrays with the values of the capacitor voltage and the capacitor current from the

equations which it evaluates.

Since t and vc are both arrays of the same size they can be plotted against one another

with the simple statement plot(t, vc); The program also adds titles and labels to the

plots. The result of the program is two new figures called figure(1) and figure(2) which

are shown below in Figure E2-3.

Capacitor voltage

12

10

Volts

8

6

4

2

0

0

0.001 0.002 0.003 0.004 0.005 0.006 0.007 0.008 0.009

Time

0.01

Capacitor current

12

10

milliamps

8

6

4

2

0

0

0.001 0.002 0.003 0.004 0.005 0.006 0.007 0.008 0.009

Time

0.01

Figure E2-3

The voltage (top) and the current (bottom) for the capacitor in this example. These two

figures were produced by Matlab running the m-file shown in Figure E2-2.

25

Solution using vectors

For those who are accustomed to other programming languages the looping structure used

in this example is a natural way to create the solution. But Matlab executes loops rather

slowly and it provides a much cleaner way of solving this problem. In Matlab it's

possible to write a single equation that operates on a vector or a matrix instead of having

to put the vector in a loop and operating on its elements piecemeal. Thus in Matlab we

can write

t = 0:.0001:.01;

%t is a vector from 0 to .01 in steps of .0001

vc = 12*(1-exp(-t/(R*C)));

ic = 12*exp(-t/(R*C));

No loop is necessary. Since t is a vector, Matlab will make vc and ic vectors and evaluate

the equation for each element of t and store the results in vc and ic. Matlab is much more

efficient at evaluating vectors than it is at doing loops. It's not always possible to avoid a

loop and make use of vectors but you should do so when you can. Figure E2-4 shows the

m-file using the vector operations. It produces the same results as before.

%Example2.m

R = 1000;

%set the value of R and C as 1k and 1uf

C = 1e-6;

t = 0:.0001:.01;

%t is a vector from 0 to .01 in steps of .0001

%use vector operations to find vc and ic.

vc = 12*(1-exp(-t/(R*C)));

ic = 12*exp(-t/(R*C));

figure(1);clf;

%Assign a figure number and clear the figure

plot(t, vc);

%plot time vs capacitor voltage

title('Capacitor voltage');

%Create a title for this graph

xlabel('Time');

%label the x axis

ylabel('Volts');

%label the y axis

figure(2);clf;

%A second figure for the current

plot(t, ic);

%plot time vs capacitor current on figure 2

title('Capacitor current');

%add titles and axis labels.

xlabel('Time');

ylabel('milliamps');

Figure E2-4

An m-file which evaluates the equations for the capacitor voltage and current as vector

equations instead of loops.

Other plot options - Subplots

Matlab provides subplots and other options that allow a user to put more than one plot on

a figure. The subplot function takes three arguments that specify the number of rows and

columns of subplots to be shown and the number of the currently selected subplot. For

example subplot(3,2,1) specifies that the current figure should have 3 rows by 2

columns of subplots and that we have currently selected the first subplot. The subplots

are numbered from left to right and top to bottom beginning with 1.

For this example we have just 2 plots so we can specify 2 rows and 1 column of subplots

for our figure. The new m-file to use subplots and the results are shown below.

26

%Example2.m

R = 1000;

%set the value of R and C as 1k and 1uf

C = 1e-6;

t = 0:.0001:.01;

%t is a vector from 0 to .01 in steps of .0001

vc = 12*(1-exp(-t/(R*C)));

ic = 12*exp(-t/(R*C));

figure(1);clf;

%Assign a figure number and clear the figure

subplot(2, 1, 1);

%specify subplots and choose the first

plot(t, vc);

%plot time vs capacitor voltage

title('Capacitor voltage');

%Create a title for this graph

xlabel('Time');

%label the x axis

ylabel('Volts');

%label the y axis

subplot(2, 1, 2);

%choose the second subplot in figure 1

plot(t, ic);

%plot time vs capacitor current on

figure

title('Capacitor current');

%add titles and axis labels.

xlabel('Time');

ylabel('milliamps');

Figure E2-5

This version of the solution plots the results in subplots as shown in Figure E2-6.

Capacitor voltage

15

Volts

10

5

0

0

0.001 0.002 0.003 0.004 0.005 0.006 0.007 0.008 0.009

Time

Capacitor current

0.01

0

0.001 0.002 0.003 0.004 0.005 0.006 0.007 0.008 0.009

Time

0.01

milliamps

15

10

5

0

Figure E2-6

This is all one figure in Matlab but the figure has 2 rows and 1 column of subplots. The

top subplot shows the capacitor voltage vs time while the bottom subplot shows the

capacitor current vs. time.

27

Example 3 – Complex Impedances

Use Matlab to evaluate the complex impedance between terminals A and B in the circuit

of Figure E3-1.

Figure E3-1

Find the equivalent complex impedance between terminals A and B.

In Matlab any variable can be real, imaginary, or complex and it can be a simple variable

or it can be a matrix. There is no special designation for these different form of variables

and they need not be explicitly declared.

For this example we will call the impedance of L1 by the variable name Z1. In Matlab

we write

Z1 = j*5;

Matlab recognizes j as 1 but the multiplication sign must be added in explicitly. You

can also use i as 1 as is done in physics and mathematics. In electrical engineering i

usually stands for current and j is taken as the imaginary number 1 . Note that if, in

your program you define either i or j to be something else, such as by using i as a loop

counter in a for loop, you can no longer use it as 1 .

The series combination of R1 and L2 will be called Z2. In Matlab this is written as

Z2 = 5 + j*8.66;

The parallel combination of R2 and C1 will be called Z3. In Matlab we can write this as

Z3 = (15*(-j*10))/(15-j*10);

The equivalent impedance at terminals A and B is then the parallel combination of Z1,

Z2, and Z3. In Matlab we write

Zab = (Z1*Z2*Z3)/(Z1*Z2+Z1*Z3+Z2*Z3);

An m-file called Example3.m is shown in Figure E3-2 which implements these equations

and displays the results. The m-file also shows how to use the abs, angle, real, and imag

functions.

28

%Example3.m

Z1 = j*5;

Z2 = 5 + j*8.66;

Z3 = (15*(-j*10))/(15-j*10);

Zab = (Z1*Z2*Z3)/(Z1*Z2+Z1*Z3+Z2*Z3);

rab = abs(Zab);

%Value of r

thetaab = angle(Zab)*180/pi;

%Value of theta in degrees

realZab = real(Zab);

%Real part

imagZab = imag(Zab);

%Imaginary part

%Use the disp function to show the results

disp('The value of Zab is ');

disp(Zab);

disp('The magnitude of Zab is ');

disp(rab);

disp('The angle of Zab in degrees is ');

disp(thetaab);

disp('The real part of Zab is ');

disp(realZab);

disp('The imaginary part of Zab is ');

disp(imagZab);

Figure E3-2

An m-file to calculate the complex impedance for the circuit of Figure E3-1.

29

Example 4 – Printing and Plotting

Matlab provides numerous print and plot options. This example illustrates the basics and

provides enough detail that you can use it for typical classroom work and assignments.

Printing Figures

Using the command print by itself either from the command line or in an m-file causes

the current figure to be sent to the printer. If there are multiple figures, you can designate

a figure number in an argument. For example print(2); will print figure 2 even if

figure 1 is the current figure. There are numerous formatting options including options

that allow you to print a figure to a file as a jpg image. See help print for details. For

classroom purposes, what is generally needed is a way to put a figure into a document.

You can do this easily by choosing EditCopy Figure from the menu on the current

figure. This option copies the current figure to the clipboard. You can then open Word

and use EditPaste to past the figure into the Word document. Word has easy to use

commands to let you resize and center the figure on your page. All of the figures in the

help files were pasted in from Matlab using this technique.

One other alternative is to push the Print Screen button on the keyboard when you have a

Matlab figure on the screen. This command copies the entire screen to the clipboard.

You can then use Paint (from the accessories menu in Windows) and past the screen

image into Paint. Paint has many options to allow you to clip out portions of an image or

to add in other images or text. Once the figure is in paint it is easy to select the figure or a

part of it and copy it to Word for further text documentation.

Printing Results

One of the frustrating things about Matlab is getting it to print your results to the screen in

some specified format. Matlab uses the old c-style print commands and the formatting

options are hard to remember if you don‟t use them often.

Any expression in Matlab which does not end in a semicolon will print results to the

screen. Thus if I enter y = 5 + 7 in an m-file or the command line I get the following:

>> y = 5 + 7

y =

12

whereas if I terminate the expression with a semicolon, the printed output is suppressed.

Matlab also has a display function called disp. The disp function is similar to omitting

the semicolon but printing is a bit more explicit and Matlab produces fewer blank lines in

the output. For example, here's how to print the value of y in the problem above using

disp.

>> y = 5 + 7;

>> disp(y);

12

30

While the disp function does a little better job than just omitting a semicolon, the output

is not formatted and you can not display multiple items on one line. To do that you have

to use the fprintf function.

The fprintf function has the following format.

fprintf(fid, format string, variable, variable, ... );

In this format, fid is file ID field. For the screen, set fid to 1 or omit it completely. The

format string is a Matlab string enclosed in single quotes that specifies the format of the

output. The variables may be in a matrix or they may be single variables separated by

commas. If the variables are in a matrix they are printed by rows.

The format string contains conversion characters that determine how the output is printed.

Each conversion character must be preceded by a percent sign (%). Adding a \n to the

format string produces a new line. The common conversion characters are:

c

d

e

f

g

i

o

s

u

x

single character

signed integer

floating point with an exponent

floating point without an exponent

general format. Uses e or f as needed.

signed integer

octal integer

string

unsigned integer

hexadecimal integer

Figure E4-1

Format characters for the fprintf command in Matlab.

This is similar to the command for formatted output in C (printf) and you can look up

more details about the print format in a C manual. Here are few examples.

i = 13; j = -45; r

= 39.567; s = 5.4136789;

Print Command fprintf(...)

Printed output

fprintf(1, '%6.3f\n', r, s);

39.567

5.414

r =39.56700000 s = 5.4137

r = 39.567 s = 5.41368

i = 13 j = -45

i =

13 j =

-45

i = d

Hello Mom!

fprintf(1,

fprintf(1,

fprintf(1,

fprintf(1,

fprintf(1,

fprintf(1,

'r =%2.8f s = %3.4f\n', r, s);

'r = %g s = %g\n', r, s);

'i = %i j = %i\n', i, j);

'i = %5i j = %5i\n', i, j);

'i = %x\n', i);

'Hello Mom!\n');

Figure E4-2

Examples of format strings and the output that they produce using fprintf.

The most commonly used format strings are f, i, and e. For the f (floating point) and e

(exponential) format strings the form of the string is '%w.d' where w is the minimum field

width and d is the number of digits after the decimal point. Note the w is the minimum

field width and the width may be longer if necessary to take care of the precision. For the

31

i (signed integer) format the general form of the format string is '%wi' where w is the field

width. The f, i, and e format specifiers are right justified.

If you are completely uncertain about the size of a number you want to output you can use

the g (general) format string which uses either f or e as needed.

You can also use fprintf to print to a file. In this case, you need an fid number which you

can get by using the command

fid = fopen('filename');

Plotting Data

Matlab supports a large number of plot options including plots for 2-D and 3-D graphs.

For class work we will look at the plot and stem functions and their options.

Plot Function

The plot function creates a 2-D graph. The normal syntax for this command is

plot(x,y);

where x and y may be matrices or functions. If x and y are both matrices then it takes

corresponding elements as the ordered pairs to make the plot. For example:

x = (0: pi/100: 4*pi);

y = sin(x);

plot (x,y);

produces a plot of sin(x) for x going from 0 to 4 in increments of /100 as shown in

Figure E4-3.

Figure E4-3

A plot of sin(x) from 0 to 4.

If you use plot(x) alone you get a plot of the values of x versus the array element

number. If x is complex it plots the real part against the imaginary part. If you use the

form plot(x, y) and x and y are complex, the real part is plotted and the imaginary part is

ignored.

Plot has a number of options to modify the color and line style.

32

Plot Options

Color and Form

You can get various line types and colors by adding a string option to the plot

arguments. The syntax is

plot (x, y, S);

where S is a string (1, 2, or 3 characters long) created with single quotes as in Basic.

Here is a table of the options.

Color

Form

b –blue

. point

c – cyan

o circle

g – green

x

k – black

+

m – magenta

- solid

r – red

*

w- white

: dotted

y – yellow

-. dash dot

_ dash

Figure E4-4

Color and form characters for use in plot options

For example

plot(x, sin(x), ‘k.’);

produces a plot of x vs sin(x) in black made out of dots. You may also spell out the

color name for clarity, e.g. 'black' or 'blue'.

Background Color

The whitebg function changes the figure background color (not necessarily to white.

The syntax is:

whitebg;

The name alone toggles the background color between white and black.

whitebg(c) - sets the background to a specific color where c is a letter form the

table above as a string. For example to get a blue background you would type:

whitebg('b');

Grid Lines

The grid function adds grid lines to an existing plot. If they are already on the plot

then grid toggles them off.

Axis

The axis function lets you scale the x and y axis after the plot has been completed.

The syntax is:

axis([Xmin

Xmax

Ymin

Ymax]);

Notice the confusing requirement for both parentheses and brackets in this command.

Title

The title function adds a title to the existing graph. The format is:

title('THIS IS A TITLE');

33

The title gets printed centered at the top of your graph.

Axis Labels

To add a label to the axis of a graph you use the xlabel and ylabel commands. The

format is similar to title.

Adding Text to a Graph

The text function allows the user to add text information to a figure at a specified

coordinate. The syntax is:

text(x, y, ‘text’);

where (x, y) is the lower left corner of the text block and „text‟ is the text added. You

can experiment to get the correct coordinates.

Subplots

The subplot (m, n, p) function divides the figure into m rows and n columns for

subplots. p is the number of the subplot that is current. For example,

subplot(2,2,1)

creates two rows and two columns for four subplots. It makes the top left current.

The following creates two graphs with y = sin(x) on the top half and z = cos(x) on the

bottom half.

clear

subplot(2,1,1);

x=(0:pi/100:4*pi);

y=sin(x);

plot(x,y);

subplot(2,1,2);

z=cos(2*x);

plot(x,z);

% 2 rows - 1 column

% x goes from 0 to 4 in steps of /100

% plots sin(x) in top subplot

% makes the bottom subplot current

% plots cos(2x) in the bottom subplot

Figure E4-5

This set of commands creates two subplots on one figure as seen in Figure E4-6.

Figure E4-6

The top subplot is number 1 and has the sin function. The bottom subplot is number 2

and has the cosine function.

34

Stem Function

The stem function creates a stem plot. This is supposed to be a plot of discrete data with

the options of the plot function (above). The syntax is:

stem(x,y);

where x and y are matrix functions. A stem plot is a sequence of lines from the y value to

the x axis. The color and line style are the same for stem as they are for plot. For

example, the following commands produce the two stem plots in Figure E4-7.

x = -2*pi:pi/10:2*pi;

y = sin(x);

figure(1);clf;

stem(x, y);

figure(2);clf;

stem(x, y, '.');

Figure E4-7

Two stem plots.

Other Useful Plot Options

semilogx, semilogy, and loglog - These are the same as the plot command with the

same syntax. They produce log (base 10) plots on either the x, y, or both axes.

Multiple plots - To get more than one plot on an axis you can string vectors together

inside the plot argument. For example

x = (0 : pi/100 : 4*pi);

plot(x, sin(x), x, cos(x));

produces a plot of x vs sin(x) and x vs cos(x) in two different colors for x from 0 to

4 in steps of /100.

hold - holds the current plot so that the next plot function is plotted without erasing

the first plot. You can use hold alone to toggle the hold function or you can use hold

on or hold off for clarity.

35

Example 5 – Step Response of RLC Network

In this example we will plot the step response of the series RLC network shown in Figure

E5-1.

Figure E5-1

A series RLC network in which the capacitor voltage is taken as the output.

Taking vc as the output and Vs as the input we can write the transfer function as

vc

1 /( LC )

2

Vs s ( R / L) s 1 /( LC )

There are two roots of the characteristic equation which are

2

R

1

R

2L

LC

2L

There are three ways to write the solution to this problem depending on whether the

discriminant is greater than zero, equal to zero, or less than zero. These three cases are

classified as overdamped, critically damped, and underdamped respectively. Using the

solution forms given in the text2 the three solutions are

Overdamped

vc (t ) Vs A1e s1t A2 e s2t

Critically damped

vc (t ) Vs ( A1 A2t )e t

Underdamped

vc (t ) Vs ( A1 cos t A2 sin t )e t

s1, 2

where r /( 2L) and 1 / LC

The values of A1 and A2 are constants determined from the initial conditions. For this

example we are doing the step response with vc(0) = 0 and dvc(0)/dt = 0.

For component values we will take Vs = 1 volt, C = 1μf, and L = 10mh. For critical

damping we want the discriminant to be equal to zero. Solving ( R /( 2L)) 2 1 /( LC) for

R gives Rc = 200Ω. For the overdamped case we will take Ro = 5Rc = 1KΩ. For the

underdamped case we take Ru = Rc/5 = 40Ω.

2

Fundamentals of Electric Circuits 2nd ed., Alexander and Sadiku, McGraw-Hill, 2004, p 329.

36

Overdamped case

Taking Ro = 1K, L = 10mh, and C = 1μf. This gives roots of s1 = -1010.2 and

s2 = -98990. The overdamped solution is

vc (t ) 1 A1e 1010.2t A2e 98990t

Applying initial conditions we have at t = 0 vc 0 gives

A1 A2 1

Setting the derivative to 0 at t = 0 gives

1010.2 A1 98990 A2 0

Solving these two equations gives A1 = -0.989898 and A2 = -0.010102. Our solution for

the overdamped case is

vc (t ) 1 0.989898e 1010.2t 0.010102e 98990t

Critically damped

Taking Ro = 200Ω, L = 10mh, and C = 1μf. This gives roots of s1 = s2 = -R/(2L)

= -10000. The critically damped solution is

vc (t ) 1 ( A1 A2t )e 10000t

Applying initial conditions we have at t = 0 vc 0 gives

A1 1

Setting the derivative to 0 at t = 0 gives

10000 A1 A2 0 or A2 10000

The solution for the critically damped case is

vc (t ) 1 (1 10000t )e 10000t

Underdamped

Taking Ro = 40Ω, L = 10mh, and C = 1μf. This gives roots of α ± jω where α = R/(2L) =

2000 and ω = 1 / LC = 10000. The underdamped solution is

vc (t ) Vs ( A1 cos t A2 sin t )e t

Applying initial conditions at t = 0 gives

A1 1

Setting the derivative to 0 at t = 0 gives

2000 A1 10000 A2 0 or A2 0.2

The solution for the underdamped case is

vc (t ) 1 (cos 104 t 0.2 sin 104 t )e 2000t

Figure E5-1 shows an m-file listing which plots all three cases on a single figure. Figure

E5-2 is the result.

37

%Example5.m

t = 0:.00001:.005;

%Overdamped - R = 1K, L = 1mh, C = 1uf

vc = 1 - .989898*exp(-1010.2*t) - .010102*exp(-98990*t);

figure(1);clf;

plot(t, vc, 'k'); %plot the overdamped case in black

%Turn on hold so all plots go to figure 1

hold on;

%Critically damped - R = 200, l = 1mh, C = 1uf

vc = 1 - (1 + 10000*t).*exp(-10000*t);

plot(t, vc, 'r'); %plot the critically damped case in red

%Underdamped - R = 40, L = 1mh, C = 1uf

w = 10000;

vc = 1 - (cos(w*t) + .2*sin(w*t)).*exp(-2000*t);

plot(t, vc, 'blue'); %plot the underdamped case in blue

%Add title and x and y axis labels

title('RLC Step Response');

xlabel('Time in seconds');

ylabel('Voltage in volts');

%Add text to mark the cases and draw a line from the

% text to each graph

text(.001, 1.3, 'Underdamped case');

x = [.001 .00043]; y = [1.3 1.2];

line(x, y);

text(.001, .4, 'Overdamped case');

x = [.001 .0005]; y = [.4 .4];

line(x, y);

text(.0015, .6, 'Critically damped case');

x = [.0015 .00015]; y = [.6 .5];

line(x, y);

Figure E5-1

This m-file plots the three step response cases on a single figure and labels each.

Figure E5-2

The graph of the three step response cases for the series RLC circuit.

38

Notes about the m-file listing:

1. The variable t is a vector and the lines

t = 0:.00001:.005;

%Overdamped - R = 1K, L = 1mh, C = 1uf

vc = 1 - .989898*exp(-1010.2*t) - .010102*exp(-98990*t);

make vc a vector of the same length as t. This kind of vector math is equivalent to the

following loop:

for i = 1:length(t)

vc(i) = 1 - .989898*exp(-1010.2*t(i)) - .010102*exp(-98990*t(i));

end

In Matlab vector math is much faster than loops.

2. A similar kind of vector math is used for the critically damped and underdamped cases.

For the critically damped case the vector math is in the equation

vc = 1 - (1 + 10000*t).*exp(-10000*t);

Note that the expression (1 + 10000*t) is a vector as is exp(-10000*t). The equation

for vc multiplies these two vectors together and Matlab uses the rules for matrix math

when multiplying vectors. So we use a special operator called dot-star (.*) which forces

Matlab to do a term by term multiplication instead of using matrix multiplication rules.

This wasn't necessary for the overdamped case since the vectors were added and the rules

for matrix addition do term by term addition. The equation for the underdamped case

also uses the .* operator.

3. The lines

text(.001, 1.3, 'Underdamped case');

x = [.001 .00043]; y = [1.3 1.2];

line(x, y);

add the words "Underdamped case" to the graph at coordinates .001, 1.3. The next two

lines form a two points and draw a line between the points. This draws the line from the

text to the curve for the underdamped case. With a little trial and error you can easily

figure out what the coordinates are for your graph. In the case of the text and line

functions, the coordinates used are the current coordinates specified by your graphs axis.

39

Example 6 – Transfer Function Plots

Matlab had a variety of functions to handle polynomials and transfer functions associated

with electronic and control systems and with digital signal processing. In this example

we will use Matlab to plot the characteristics of passive RLC filters.

Consider the circuit shown in Figure E6-1.

Figure E6-1

A third order passive Butterworth filter circuit.

If we replace that portion of the circuit to the left of A-B with its Thevenin equivalent

circuit and the portion to the right of A-B with its parallel equivalent impedance, we can

write the transfer function using the voltage divider law as

V2

ZP

. The circuit impedances are shown in Figure E6-2.

Vth Z th Z P

Figure E6-2

We have divided the circuit at A-B and replaced the left and right portions with their

equivalents.

The parallel impedance of R2 and C2 is given by Z P

1(1 / S )

1

1 1/ S S 1

Likewise, the value of Zth is seen to be the parallel combination of R1 and C1 in series

1(1 / S ) 2S 2 2S 1

with L2. We can write Z th 2S

.

1 1/ S

S 1

To find Vth we find the open circuit voltage at A-B. This allows us to ignore L2 since no

current is flowing through it if the circuit is open. Vth can be found by using the voltage

divider law as

V

1/ S

Vth V1

1

11/ S S 1

40

Using the voltage divider law we write

V2

V2

1 /( S 1)

1

2

2

1

Vth V1 /( S 1) 2S 2S 1

2S 2S 2

S 1

S 1

But the transfer function H(S) is the ratio of V2/V1. We can write H(S) as

0.5

H (S ) 3

S 2S 2 2S 1

To plot this function in Matlab we can use the m-file shown in Figure E6-3 which uses

the freqs function. The freqs function assumes that the numerator and denominator

polynomials are specified as coefficients of S. Thus, the numerator polynomial is simply

num = 0.5 but the denominator polynomial is den = [1 2 2 1];. The function freqs returns

a vector which has the complex evaluation of the transfer function stored in a vector

called H. The magnitude of H is given by abs(H) and gives us the magnitude of the gain

of the circuit as a function of frequency. The phase angle of H is given by angle(H) and

gives us the phase angle in radians as a function of frequency.

%Example6.m

w = 0:.01:10;

%frequency vector in radians

num = 0.5;

den = [1 2 2 1];

H = freqs(num, den, w);

figure(1);clf

subplot(2, 1, 1);

plot(w, abs(H));

%plot the magnitude on the top part

title('Magnitude and Phase Plot');

ylabel('Gain');

xlabel('Radians');

subplot(2, 1, 2);

plot(w, angle(H)*180/pi); %plot the phase on the bottom part

ylabel('Degrees');

xlabel('Radians');

Figure E6-3

An m-file plot of the magnitude and phase of a transfer function given by

Figure E6-4

The magnitude and phase plot.

41

H (S )

0.5

S 2S 2 2S 1

3

Example 7 – Plotting LtSpice Simulations in Matlab

In LtSpice, after doing a simulation you can save the data which was used to generate the

simulation and import it into MATLAB for further manipulation. Matlab has a loadfile

command that allows such files (with minor modification) to be read into Matlab and

operated on using Matlab's functions.

There are two advantages to reading LtSpice files into Matlab. First Matlab creates

"prettier" reports and graphs that are easier to integrate into Word. Second Matlab can do

many functions that can't be done easily in LtSpice and this gives you an opportunity to

enrich you simulation.

In this example, we will do a simulation in LtSpice, save the file, modify it for reading

into Matlab, and finally read it into Matlab to make a plot.

We begin by constructing the circuit in Figure E7-1 using LtSpice. The simulation looks

at Vin and Vout

Figure E7-1

Circuit for simulation in Workbench.

After the simulation runs click once on the plot and select File → Export. This will bring

up a screen shown in Figure E7-2. Select a path and file name and click OK to save the

data as a text file. You can exit LtSpice

42

Figure E7-2

The File→Export menu from LtSpice

The saved file is a simple text file that you can open and examine using Notepad or

Word. The file consists of some header information followed by three columns of data

giving the time base and the corresponding voltage levels for the two nodes. Figure E7-3

shows the beginning and end of this file.

time V(n002)

V(n003)

0.000000000000000e+000 0.000000e+000

1.896585271020485e-009 -1.779854e-006

3.793170542040970e-009 -7.007942e-006

5.689755813061455e-009 -1.568426e-005

7.586341084081940e-009 -2.780881e-005

9.482926355102426e-009 -4.338160e-005

1.137951162612291e-008 -6.240262e-005

1.327609689714339e-008 -8.487187e-005

2.556419391731497e-008 -3.034966e-004

4.418355913658504e-008 -8.520387e-004

…

0.000000e+000

2.383319e-005

4.766639e-005

7.149958e-005

9.533277e-005

1.191660e-004

1.429992e-004

1.668324e-004

3.212491e-004

5.552270e-004

1.998464199406124e-001

1.998609112380335e-001

1.998787348420469e-001

1.998980380558890e-001

1.999218366406368e-001

-1.640545e+000

-1.529819e+000

-1.375973e+000

-1.190083e+000

-9.370503e-001

-7.143645e-001

-8.052113e-001

-9.070134e-001

-1.004364e+000

-1.103188e+000

43

1.999502564861356e-001

1.999903189323086e-001

2.000000000000000e-001

-1.186708e+000

-1.250910e+000

-1.249292e+000

Figure E7-3

-6.086052e-001

-1.206329e-001

1.571833e-014

The exported data file opened using Notepad.

Matlab can read text files using the load 'filename' command. However, Matlab expects

these files to contain only the data and not any header information. If we try to read the

exported text file with Matlab's load command we will generate an error. To correct this

we modify the file by deleting all of the header information from the top of the file down

to the first line of data. The first line of the file should read

0.000000000000000e+000 0.000000e+000

0.000000e+000

Save this amended file with a new name such as Ex7.txt. Ex7.txt can now be read into

Matlab and stored as a vector having one row for each row in the file and three columns.

Figure E7-4 shows an m-file that reads Ex7.txt into a variable called "scope". We then