Memo Potential Policy-Related Uses of Measures of Consumption among Low-Income Populations

Memo

Potential Policy-Related Uses of Measures of Consumption among Low-Income Populations

Susan E. Mayer

University of Chicago, Harris School

October 18, 2004

Summary

Income, expenditure, cons umption, and material living conditions are different concepts that tell us different things about economic well-being. They are not interchangeable and should not be used as proxies for one another because at least for lowincome populations they are often not highly correlated. This memo argues that to assess levels or trends in economic well-being among poor families requires considering all three measures and resolving the inconsistencies in the picture of economic well-being they provide. Which measure of well-being should be used to assess eligibility, set benefit levels, and assess program effectiveness depends on what government programs are intended to accomplish.

Assessing Economic Well-Being

Most people are interested in family income because they expect income statistics to tell them something about how much families consume and their material living conditions. When “real” income increases, we expect consumption to increase and living conditions to improve. When real income declines, we expect consumption to decline and living conditions to deteriorate. Similarly we expect measures of income poverty to tell us something about the number of people and families suffering from material hardships and the poverty gap to tell us something about the severity of material hardships. Yet a considerable amount of evidence suggests that among families in the bottom 20% of the income distribution:

•

Consumption and income are not highly correlated and in fact expenditures and consumption often exceed income for this group (Meyer and Sullivan 2003,

Federman et al. 1996, Rogers and Grey 1994, Mayer and Jencks 1993, Slesnick

1993). Nor are expenditure and consumption necessarily correlated (Aguiar and

Hurst 2004).

•

Income and measures of individual material hardship are not highly correlated

(Federman et al. 1996, Jencks and Mayer 1989, Mayer and Jencks 1993). Nor are various scales and other composites of material living conditions highly correlated with income (Mayer 1997, Mirowsky and Ross 1999).

•

Consumption and measures of individual material hardships are not highly correlated (Meyer and Sullivan 1993, Mayer and Jencks 1993)

•

Trends in income, consumption and material hardships are not the same (Slesnick

1993, Mayer and Jencks 1993, Jencks, Mayer, and Swingle 2004). During the

1970s and 1980s when income in the bottom 20% of the income distribution was declining and poverty was increasing, consumption hardly changed and material living conditions improved in this part of the income distribution. During the

1990s the trends in income, consumption and material living conditions were similar (Jencks, Mayer, and Swingle 2004).

•

Controlling for level of income, material hardships among low- income groups vary across countries (Mayer 1993).

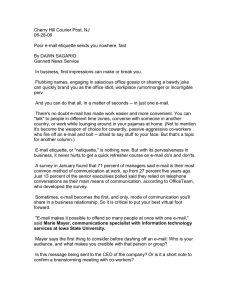

Economic theory clearly distinguishes between income and expenditure and between expenditure and consumption (e.g. Meyer and Sullivan 2003, Augiar and Hurst

2004, Slesnick 1993, Jorgenson 1998). Economic theory and empirical evidence on the relationship between consumption and living conditions is less well developed and is an area for further research. Nonetheless, Figure 1 attempts to provide a rough schematic interpretation of some of the main factors linking income, expenditure, consumption and living conditions. While Figure 1 may be incomplete, it highlights some of the main reasons why the correlation between different measures of economic well-being is far from 1 among low-income populations. It suggests that two families with the same true current income can have very different levels of current consumption, depending on how much they save, borrow, pay in taxes, receive in kind, and how much they receive in service flows from past consumption. Figure 1 implies, for example, (and empirical research confirms) that given the same income and the same expenditure families with

older members are likely to have greater levels of consumption than families with younger members because they are more likely to ha ve accumulated durables and housing in the past that they continue to consume in the present (Aguiar and Hurst 2004,

Mirowsky and Ross 1999). Families with the same current consumption can have different living conditions depending on their needs and the efficiency with which they consume (sometimes called “temperate lifestyle”). Variations in needs come from differences in family size, prices, health, and so on.

These same factors can lead to different trends in income, consumption and living conditions. When reported income increases and all else is equal, consumption will increase and living conditions will improve. But over time all else is seldom equal.

Hence when reported income changes the distribution of reporting errors, taxes, savings, borrowing, noncash benefits, assets, consumer efficiency, household size, and other factors affecting the needs of households can also change. This is why the trends in these measures of well-being diverged dramatically in the 1970s and 1980s.

Because income, consumption and living conditions are not highly correlated, conclusions about the well-being of the poor depend a great deal on which measure we consider. A general principle for both policy makers and social scientists is that a direct measure of the thing you want to know about provides better information than an indirect measure. If one is interested in the living conditions of families, consumption is a better measure than expenditure and expenditure is a better measure than income. (See Meyer and Sullivan, 2004, for an empirical demonstration of this point.) But a direct measure of material living conditions would be even better.

All of this is well-known to both academic researchers and civil servants who work on social welfare policy. Yet it still largely ignored. Both the federal government and most academic researchers continue to rely almost exclusively on income measures to assess both the level and trend in the well-being of the poor. Reliance on income continues partly because of conceptual and measurement issues. Income is an easy-tounderstand concept, it is relatively easy to measure (although difficult to measure accurately), and it has been measured relatively consistently for decades. In contrast it is difficult to measure consumption from existing expenditure surveys and the samples in these data sets are relatively small making some kinds of analysis difficult. Consistent

consumption data is available for a relatively short time frame. The federal government and academic researchers have spent a great deal of effort in the last decade developing measures of specific material hardships of interest to policy makers, such as food insecurity, and in measuring a variety of material deprivations in the same data set so that we can assess hardship in several domains at once. This allows us to begin to understand trade-offs that families make. Nonetheless there is much less agreement about how to measure material living conditions than there is about how to measure income and consumption. (See HHS, ASPE 2004 for discussion of measurement issues related to material well-being.)

The unwillingness of the federal government and many scholars to consistently provide a broader picture of the well-being of the poor is also due to political inertia and academic conservatism. In the long run a more aggressive research agenda on the relationship between income, expenditure, consumption, and living condition can help overcome the measurement and conceptual issues as well as inertia. For example the following questions come to mind:

•

How important are each of the factors in Figure 1 to the disjunction between income, consumption and living conditions? A significant part of the difference in the trend in income and living conditions is accounted for by taxes and inadequate adjustments to income for changes in prices (Jencks,

Mayer and Swingle 2004). Some of the disparity between income and consumption is accounted for by mis- measurement of income (Meyers and

Sullivan 2004) and by life-cycle changes in consumption that results from previous expenditure (Aguiar and Hurst 2004, Mirowsky and Ross 1999). But we know much less about the importance of variations in the needs of families or prices.

•

How can we create a direct summary measure of living conditions that takes into account not only hardships but “luxuries.” Two techniques come to mind, namely randomly selecting a sample of living conditions or measuring all of them. Neither task is likely to be more difficult than trying to measure all aspects of consumption accurately.

•

By world standards and probably by the standards of rich democracies, serious material deprivations are rare even among low- income American families.

Yet because the rich are very rich in the United States, the living conditions of low- income families may be much worse relative to affluent families in the

United States compared to other countries. What is it that we mean for government policy to improve - absolute deprivation or relative deprivation?

•

Because so few families experience severe material hardships (such as eviction, hunger, serious untreated illness and so on) and even fewer experience multiple severe problems, and because the families that do experience severe or multiple severe problems are sometimes not income poor, it suggests that low resources alone is not sufficient to cause serious deprivation. This raises the question of what factors cause families to experience serious material deprivation.

•

Is income, consumption or living conditions a better indicator of poor social outcomes and is this relationship causal or correlational? Some evidence suggests that net of income, material hardships are associated with a greater likelihood of depression (Mirowsky and Ross 2001) and even controlling observed and unobserved characteristics of parents including their income, material living conditions are associated with children’s cognitive skills, adolescent problem behaviors, and educational attainment (Mayer 1997).

More information on the consequences of low income, consumption and material living standards can help us understand what the government should be most concerned with.

Program Eligibility and Program Evaluation

If current reported income is a weak measure of living conditions, using it for important policy purposes such as determining program eligibility and evaluating programs might be a mistake. Fortunately eligibility for most government programs does not rely solely on income, or at least on income as it would be reported on a survey.

Eligibility rules often include asset tests and adjustments to income for needs such as the size, age, and disability of family members. These requirements implicitly recognize that

income alone is inadequate for assessing families’ needs. Subsidies or income exclusions for transportation and child care recognize that consumption of housing, food and other necessities are affected by these needs. Still families can easily hide many forms of income especially income earned in the unofficial economy and a consumption test, if one could be devised, might reduce this possibility. Nonetheless, Meyer and Sullivan

(2004) persuasively argue in favor of using income to assess program eligibility.

Eligibility for some programs is limited to individuals in locations (such as schools or neighborhoods) with high levels of officially measured poverty. It is not at all clear whether substituting a measure of low consumption or high levels of material hardship would alter the distribution of these funds because we know little about the geographical distribution of hardships or how the geographical distribution of low consumption corresponds with the geographical distribution of low income.

Meyer and Sullivan (2004) argue in favor of using consumption rather than income to set benefit levels and to evaluate income transfer programs because consumption is better measured than income and because it is more highly correlated than income with material living conditions. Whether consumption or income is a better tool for evaluating income transfer programs depends on the purpose of the program. It seems perfectly acceptable to evaluate an income transfer program by whether it increases income if that was the goal of the program. But policy makers should not mistake an increase in income for an increase in consumption or living standards. If they want to know whether the program accomplished these goals they will have to measure those outcomes. Because most income transfer programs have multiple purposes, they probably need to be assessed against multiple outcomes.

To fulfill requirements of the federal Government Performance and Results Act

(GPRA) government agencies are required to develop a strategic plan and report annual performance in executing the plan. Some agencies use prevalence estimates of measures of material hardships in fulfilling this mandate. For example, the Food and Nutrition

Service of the USDA uses a measure of food security as a measure of the performance of the food stamp program. HUD has uses home ownership rates as one of its performance measures. This is probably an inappropriate use of measures of material living conditions. A performance measure should be something over which the program has

direct control. Food security like home ownership is influenced by many factors outside the control of either USDA or HUD, which mainly provide noncash resources to lowincome families. A rise in the number of households that are food insecure can be due to an increase in poverty, changes in the price food, or changes in the price of goods that compete with spending on food. For example, if rents increase food insecurity might increase. But it is not clear that this would represent a failure on the part of the food stamp program.

References

Aguiar, Mark and Erik Hurst. (2004). “Consumption vs Expenditure.” NBER Working

Paper 10307.

Federman, M. T.Garner, K. Short, W. Cutler IV, J. Kiely, D. Levine, D. McGough, and

M. McMillen (1996). “What Does It Mean to Be Poor in America,” Monthly Labor

Review 119 (5); 3-17.

Jorgenson, Dale. (1998). “Did We Lose the War on Poverty?” Journal of Economic

Perspectives , 12(1): 79-96.

Mayer, Susan E. (1997). What Money Can’t Buy: Family Income and Children’s Life

Chances . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Mayer, Susan E. (1993). "Living Conditions among the Poor in Four Rich Countries".

Journal of Population Economics, 6:266-286.

Mayer, Susan E. and Christopher Jencks. (1989). “Poverty and the Distribution of

Material Resources.” Journal of Human Resources , 24: 88-114.

Mayer, Susan E. and Christopher Jencks. (1993). "Recent Trends in Economic Inequality in the United States: Income vs. Expenditures vs. Material Well-being" in Poverty and

Prosperity in America at the Close of the Twentieth Century , edited by Edward Wolff and

Demitri Popademitrious. New York: St. Martin's Press.

Meyer, Bruce and James X. Sullivan. 2003. “Measuring the Well-being of the Poop

Using Income and Consumption.” NBER Working Paper 9760.

Mirowsky, John and Catherine Ross. (1999). “Economic Hardship across the Life

Course.” American Sociological Review 64(4): 548-569.

Mirowsky, John and Catherine Ross. (2001) “Age and the Effect of Economic Hardship on Depression.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 42(2): 135-150.

Rogers, John and Maureen Grey. 1994. “CE Data: Quintiles of Inocme vs Quintiles of

Outlays.” Monthly Labor Review , 117(12):32-37.

Slesnick, Daniel T. 1993. “Gaining Ground: Poverty in the Postwar United States.”

Journal of Political Economy 1901(1): 1-38.

Reported

Current

Money

Income

Unreported

Money

Income

True

Current

Money

Income

Savings

Borrowing

Figure 1

Determinants of Living Conditions

Past

Expenditure on Durables

& Housing

Service Flows from Durables &

Housing

Expenditure for

Current

Consumption

Current

Expenditure on Durables

& Housing Non cash Income

Current

Money

Expenditure

Taxes

Consumer

Efficiency

Family Size

Age of Family

Members

Health

Work Expenses

Prices

Current

Consumption

Need for

Current

Expenditures

Living

Conditions

Other

Outcomes