NA TIONAL SER VICE GOVERNMENT

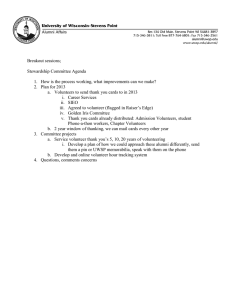

advertisement