Document 13957924

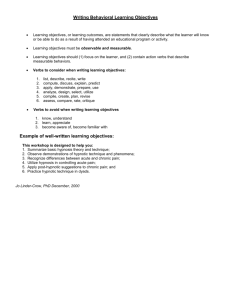

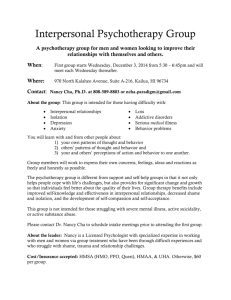

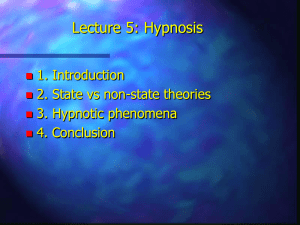

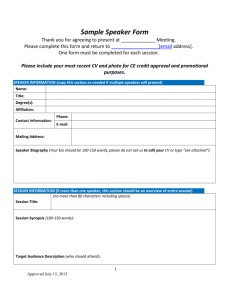

advertisement