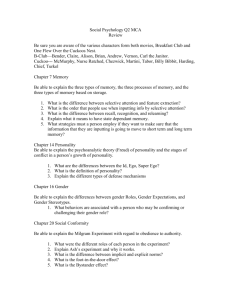

Document 13957892

advertisement