Teaching English Phonetics and Phonology in Colombia Bozena Lechowska,

advertisement

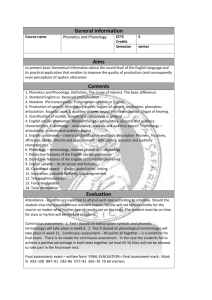

Teaching English Phonetics and Phonology in Colombia Bozena Lechowska, Universidad Industrial de Santander, Bucaramanga, Colombia bozena@uis.edu.co The objective of this paper is to present an overview of the phonological component of a five-year teacher training programme at the School of Languages, Universidad Industrial de Santander, Colombia. Introduction School of Languages at UIS is part of the Faculty of Human Sciences and offers two BA programmes, one in English, the other one in Spanish. Although both degrees are geared up for the teaching profession, one major difference is responsible for the fact that the programmes vary considerably. The command of language, object of study, makes it hardly possible for the students of English to initiate their studies at the same level of linguistic sophistication as their Spanish-speaking counterparts. Our students enter the university with a very basic range of linguistic resources (pre-intermediate level), which is why the following five semesters (two and a half years) are spent on intensive language development strand in the overall curriculum. Students are supposed to achieve FCE level at the end of the five-semester course in English. Course Description A three-semester course in English Phonetics and Phonology takes place at the very beginning of the degree and it is carried out in parallel with the first three components of the language development strand. The course consists of three sessions a week: two 90-minute sessions and one of 45 minutes. One of the longer sessions will usually constitute the lecture while the remaining two will consist of practical back-up classes run either in a language laboratory with audio material or run in a room equipped with a computer and a video beam where students work with multimedia material. The initial semester of English Phonetics and Phonology is dedicated to segments while the remaining two deal with suprasegmentals. There will usually be three groups of about 12 to 15 students for each level and there will usually be a number of teachers in charge of the courses. To ensure the highest amount of standardisation possible all students participating at a particular level of the course will sit the same written exam. Every exam consists of three equally weighted parts: theoretical foundations, transcription based on auditory discrimination and sound production. A section of the oral exam always involves reading aloud phonetically weighted textual material and/or phonetically transcribed texts. Teaching tools The main course book covered over the three-semester period is Roach, P. 2000. English Phonetics and Phonology: a practical course. Third edition. Cambridge: CUP. It is supplemented by a series of other materials to reinforce particular learning objectives. The main sources are: Bradford, B. (1994) Intonation in context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Brazil, D. (1994) Pronunciation for Advanced Learners of English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Cruttenden, A. (2001) Gimson's Pronunciation of English. Sixth edition. London: Edward Arnold. Gimson, A.C. (1981) A Practical Course of English Pronunciation. London: Edward Arnold Publishers. Hancock, M. (2003) English Pronunciation in Use. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Hewings, M. (2004) Pronunciation Practice Activities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Kenworthy, J. (2000) The Pronunciation of English: A Workbook. London: Edward Arnold. Kreidler, C. W. (2004) The Pronunciation of English. Second edition. Blackwell Publishing. Mott, B. (2000) English Phonetics and Phonology for Spanish Speakers. Edicions Universitat de Barcelona. O'Connor, J.D. (1980) Better English Pronunciation. Second edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Roach, P., J. Hartman & J. Setter, (eds.) (2003) English pronouncing dictionary. 16th edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Wells, J.C. (2000) Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Second edition. Longman. To enhance both the teaching and the learning process the following multimedia material is used throughout the three-semester course: Cauldwell, R. ( 2002) Streaming Speech. Birmingham: Speechinaction. Friend, D. (2000) Pronunciation Programme. Sky Software House. Handke, J. (2000) The Mounton Interactive Introduction to Phonetics and Phonology. Berlin, New York: Mounton de Gruyter. Protea Textware (2001) Connected Speech. Protea Textware Pty Ltd. Hurstbridge Victoria. Since visual clues are as important as auditory ones, the above mentioned computer software provides valuable contribution to the learning process. Ideally, it should be employed by students on an individual basis, however, in our present situation this is impossible. Thus, the material is used by means of a video beam which makes it available to a group of students. In general, it would seem that the material is being used to very good effect even though students can’t work at their own individual pace. Nonetheless, students can work in a computer lab at their own pace with materials that are available on the web to support the learning of phonetics and phonology. The role of English Phonetics and Phonology within the teacher education programme The underlying assumption behind the curriculum design reflects the belief that teachers need a well-rounded concept of the phonology of the language they are going to teach. They should be respectably solvent in both segmental and suprasegmental features of the target language and they should have a solid grounding in “theory and knowledge about how the sound system of the target language works” (Burgess and Spencer, 2000). Thus the phonological training in our programme involves our students learning about the sounds of English as well as learning how to produce them. It is expected that this interplay of theoretical and practical aspects will be highly beneficial in helping students to become both proficient speakers of English and effective teachers of the language. As observed by Dziubalska-Kołaczyk (2002) “Making the learner metalinguistically aware of phonetics, phonology, morphology, syntax as well as socio-pragmatics will facilitate his/her acquisition of a second language, i.e. the development of second language competence.” It our belief that our students’ future teaching practice will demand precisely this: heightened quality of competence originated by metalinguistic awareness. Trainees will become linguistic models for their pupils and as stated by Gimson (2001) one of their major responsibilities will be centred around providing as close approximation to a chosen model of pronunciation as possible. A questionnaire In order to find out whether our predicted outcomes coincided with students’ perception of the role of English Phonetics and Phonology within the programme, students were asked a series of questions. Following two Polish examples set by DziubalskaKołaczyk et al (1999) and Sobkowiak (2002), I embarked upon determining the current situation in our school. Data were obtained by means of a questionnaire which was responded by 67 second and third semester students enrolled in our teacher training programme. The first question referred to the role of English Phonetics and Phonology in mastering the pronunciation of English. 65 students out of 67 found the courses very helpful in this respect. When asked to give examples of pronunciation problems solved thanks to English Phonetics and Phonology students came up with an impressive list of benefits offered by the courses. The responses clearly indicate that the courses have the potential to help students overcome almost any phonetic disadvantage they might experience. Students write about segmental achievements such as coming to grips with the system of English vowels and consonants, vowels contrasts, pre-fortis clipping, aspiration, and consonant clusters. They also mention individual sounds such as schwa /ə/, dark /ɫ/, palatoalveolar fricatives /ʃ, ʒ/ and affricates /ʤ, ʧ/ which have reportedly improved as a result of English Phonetics and Phonology classes. Many state highlighting the differences between Spanish and English sound systems as a valuable asset to the courses. As far as the suprasegmental domain is concerned students claim that they no longer experience problems with word stress and weak forms, that they are no longer puzzled by liason and assimilation (particularly the problem of realization of “-(e)d” and “-(e)s” endings has been solved), and that they have become much more sensitive to the role of intonation in communication. But students responses to this question go far beyond their immediate articulation problems. They state that as a result of English Phonetics and Phonology classes their general listening comprehension skills have greatly improved, they understand native speakers of English much better and they feel much more confident while sitting listening comprehension component of their English exams. In the same vein, students claim that their speaking skills have been greatly enhanced, some even claim they are getting much better grades for their oral exams. Others maintain that while English Phonetics and Phonology do a lot to promote trainees’ linguistic development, not enough attention is given to pronunciation matters in English classes because apparently some teachers feel that courses in English Phonetics and Phonology should take care of whatever problem arises in this respect. These remarks seem to stem from some students’ beliefs that far better results could be achieved if more time was spent on giving students a chance to practice what they have learnt in English Phonetics and Phonology. The third question had to do with the relative importance of pronunciation as opposed to grammar or vocabulary. 40 % of the respondents believe that good pronunciation is more important than grammar or vocabulary in English, 45% do not agree with the statement and 15 % couldn’t make up their minds. This seems to confirm the general tendency within TEFL where grammar and vocabulary teaching have traditionally been given more emphasis than pronunciation. When asked whether they practice their pronunciation regularly most of the students responded “yes” (91%). Reportedly, only 9% of the respondents do not practice regularly. The high number of yeses might perhaps by explained by the respondents wish to create a picture-perfect image of themselves or their willingness to please the researcher. At the very least, the answers here seem to indicate that students are aware of the importance of regular, out-of-class practice. 58 % of the respondents believe that listening to English is more difficult than speaking it as opposed to 34 % who are of a different opinion. The relatively high proportion of yeses in this case appears to reflect the fact that students are frequently exposed to fast native speech. It also seems to indicate students’ awareness of the differences involved in listening to native speakers in natural communicative settings, probably with a fair amount of background noise as opposed to speaking under classroom conditions to interlocutors who share a similar set of non-native features in their interlanguage. It was very encouraging to find out that more than two thirds of our students have used phonetic transcription in their classroom notes. The experience of active transcribing is particularly valuable in the case of learners whose native language exhibits a relatively straightforward relationship between sound and spelling. However, the classroom transcription data become less optimistic when contrasted with students’ reaction to the next question. Only 57 % of the respondents do not believe that phonetic transcription of English is too difficult for them. This goes counter to what many students’ were signalling as benefits of English Phonetics and Phonology classes: namely increased ease and confidence of dictionary use due to the knowledge of phonetic transcription. The relatively high number of respondents (43%) who find transcription too difficult for them may have been reacting negatively to the complex nature of listening geared up for transcription as opposed to reading from transcription. Earlier I remarked that too much attention given to grammar and vocabulary in general English classes attracted some criticism from students. In the light of this it won’t be surprising to find out that a vast majority of students (97%) expressed a wish to have more pronunciation practice during their studies. The questionnaire also provided me with an opportunity to compile a list of different aspects of the English phonetic system according to their perceived difficulty by our students. Not surprisingly perhaps our trainees list suprasegmental features as their greatest challenge in the attempt to achieve an effective spoken English performance. Intonation is perceived to be the most difficult aspect, followed by such features as weak forms, assimilation and word stress while for other students consonant clusters remain problematic. Surprisingly, the scores for vowels were much lower than expected. This could probably be explained by the fact that at the time when questionnaire was applied students were immersed in the study of suprasegmental features so their perception might have been influenced by their immediate needs. Conclusion In this paper, I have described the phonological component of a five-year teacher training programme at the School of Languages, Universidad Industrial de Santander, Bucaramanga. I have also discussed the findings of a questionnaire conducted among our students. They seem to confirm the claims by Dziubalska-Kołaczyk (2002) referring to the usefulness and importance of explicit formal instruction in phonetics and phonology within the context of teacher education programmes. References Cruttenden, Allan (2001) Gimson's Pronunciation of English. Sixth edition. London: Edward Arnold. Burgess, J. & S. Spencer (2000) Phonology and pronunciation in integrated language teaching and teacher education. System 28, pp. 191-215. Dziubalska-Kołaczyk, K., J, Weckwerth & J. Zborowska (1999). “Teaching English phonetics at the School of English”, AMU, Poznań, Poland. PTLC99 (Phonetics Teaching and Learning Conference) UCL, London 14-15 April 1999. Dziubalska-Kołaczyk, K. (2002) Conscious competence of performance as a key to teaching English. In: Waniek-Klimczak, E. & P. J. Melia (eds.) Accents and Speech in Teaching English Phonetics and Phonology. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. Sobkowiak, W. (2002) English speech in Polish eyes: What university students think about English pronunciation teaching and learning. In: Waniek-Klimczak, E. & P. J. Melia (eds.) Accents and Speech in Teaching English Phonetics and Phonology. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.