The characteristics of placing prominences by suggestions.

advertisement

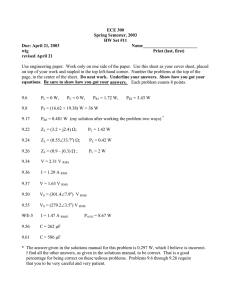

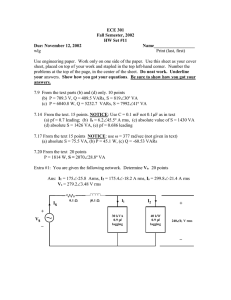

PTLC2005 Tsutomu Sato The characteristics of placing prominences by Japanese Learners...1 The characteristics of placing prominences by Japanese learners of English and pedagogical suggestions. Tsutomu Sato, Meiji Gakuin University, Tokyo 1 Introduction The main idea of this paper is that not only a pitch peak which is often called a nucleus but also intensity should be taken into consideration in determining prominent syllables in actual utterances. More specifically, first of all, it will be investigated how much amplitude effect which is marked by the peak of the root-mean-square (RMS, hereafter) envelope is involved in realizing contrastive stresses in production experiments by both native speakers of English and Japanese learners of English. Second, so-called ‘unEnglish’ features peculiar to the Japanese learners will be indicated. Figure 1. The utterance ‘No, there’s ONE in the hall as well’ by CH. Both of RMS and Pitch peaks are on the word ‘ONE’ in this case PTLC2005 Tsutomu Sato The characteristics of placing prominences by Japanese Learners...2 2 Prominence, Intensity, and RMS Envelope Tench (1996:53) lists the following seven features to identify tonic syllables: pitch peak, maximum pitch range, kinetic tone, loudness peak, decrescendo, tempo marking, and pause. It is assumed in this study that the peak of RMS envelopes can be one of the measures to represent the fourth factor, loudness peak, following the statement by the previous studies such as Rosen and Howell (1991:32), Johnson (1997:36), and Hayward (2000:43) that the intensity of a wave is proportional to the square of its amplitude. As an example, the waveform, RMS envelope, and pitch contour of one of participants in this study, CH, are shown in Figure 1 3 Experimental Procedure Three native speakers of Australian English, CH (M, 23), LC (F, 20), YL (F, 20) and three Japanese returnees from Australia, AH (F, 22), TW (F, 22), MN (F, 21) are participants of this experiment. They were individually asked to play roles of both A and B in the following dialogue, which is based on Bradford (1988:44), with five repetitions: A: Come on. The taxi's waiting. B: Did you say TAXI (i) ? I thought we were going in your CAR (ii). A: Yes, well, I had planned to. But I'll explain later. You've got to be there in an HOUR (iii). B: NOT an hour (iv). The plane doesn't leave for TWO hours (v). Anyway, I'm ready now. We can go. A: Now-- you're taking just one CASE (vi). Is that right? B: No, there's ONE in the hall as well (vii). A: Gosh! What a lot of stuff! You're taking enough for a MONTH (viii), instead of a WEEK (ix). B: Well, you can't depend on the weather. It might be COLD (x). A: It's NEVer cold in Sydney (xi). Certainly not in May. Come on. We really must go. The words in bold letters are assumed to be in contrast but were not indicated on the sheet for participants to read in actual experimental conditions. PTLC2005 Tsutomu Sato The characteristics of placing prominences by Japanese Learners...3 4 Result and Discussion Out of the five-time repetitions, the middle three dialogues were analyzed. In the measurement, possible effects by declination were not considered this time. Three words marked by RMS peaks are listed with their values in the table 1. (i) TAXI (ii) CAR (iii) HOUR (iv) NOT (v) TWO (vi) CASE (vii) ONE CH LC AH MN TW you 6626 say 8029 you 7032 say 6945 say 6900 taxi 7646 say 6764 say say 6957 say 7930 you 6898 say 7170 say 6840 say 7461 7926 taxi 7179 say 6960 say 6752 taxi 7648 thought 7029 thought 8343 thought 7478 car 7148 I 7324 car 7567 thought 7033 thought 8124 car 7197 car 7276 going 6946 thought 7857 thought 7164 thought 8271 car 7047 going 7314 going 7062 car got 6882 got 8171 got 7331 got 7244 got 7000 got 7627 got 7055 got 8184 got 7314 there 7345 got 6811 got 7754 there 6898 there 8195 got 7448 got 7294 got 6997 got 7815 not 6779 hour 8032 not 7212 hour 7100 hour 6843 an 7382 not 6974 not 8110 not 7198 hour 7047 hour 6761 hour 7361 not 7081 not 8083 not 6991 hour 7044 not 6962 hour 7628 plane 6616 leave 8071 hours 6930 doesn't 7303 hours 6780 leave 7692 plane 6988 leave 8043 doesn't 6882 doesn't 7211 hours 6862 leave 7692 (x) COLD (xi) NEVer 7703 plane 7180 leave 8034 doesn't 7075 doesn't 7202 doesn't 6845 hours 7605 taking 6852 case 8135 taking 7442 case 7296 one 6980 taking 7413 case 6754 taking 8170 are 6999 case 7217 one 6973 taking 7381 taking 6938 just 8216 you 7313 are 7336 are 6832 are 7687 one 6695 hall 8148 one 7465 there 7305 one 6982 one 7570 well 7013 hall 8226 one 7386 there 7366 hall 6873 hall 7666 hall 7061 hall 8169 one 7445 there 7273 one 6953 well 7548 6405 month 8110 month 7254 you 7190 enough 6836 month 7490 Taking 6903 taking 8177 month 7149 are 7312 enough 6973 for 7484 taking 6906 enough 8201 month 7298 you 7250 enough 6748 month 7476 instead 6025 week 7884 week 7192 of 6912 instead 6978 week 7666 instead 6504 week 8138 week 7188 instead 7182 instead 6825 week 7596 instead 6437 instead 7914 week 7220 instead 6879 instead 7046 week 7711 might 6451 cold 8228 might 7236 might 7025 cold 6892 cold 7675 might 7011 might 8142 might 7279 cold 7197 might 6741 cold 7747 might 6865 cold 8041 might 7426 might 6913 might 6976 cold 7697 never 6731 never 8248 never 6904 never 7072 never 6978 never 7655 never 7185 never 8265 never 7146 never 7181 never 6889 cold 7677 cold 7075 never 8327 never 7197 never 7188 cold 6870 cold 7946 (viii) MONTH taking (ix) WEEK YL PTLC2005 Tsutomu Sato The characteristics of placing prominences by Japanese Learners...4 As a whole, the degree of agreement between each word in contrast shown in the leftmost column and words which contain RMS peaks is rather low, except for the words of negation, i.e., (xi) Never and (iv) not in the cases of native speakers. Another finding is that verbs and auxiliary verbs tend to attract the peaks of RMS envelopes. 5 Japanese Characteristics in RMS Envelopes The overall RMS envelope patterns were compared in the data by native speakers and Japanese returnees. As an illustration, the patterns of (ix) instead of WEEK by YL and AH are compared in Figure 2 RMS peaks can be found on the word WEEK in YL, whereas an RMS peak is on the Figure 2 RMS patterns by YL and AH word instead in the case of AH. This example of AH shows successive downstepping peaks, which is typical of many Japanese learners who tend to intensify an initial word in phrases or clauses. 6 Concluding remarks In the presentation, the analysis of correlation between RMS peaks and pitch peaks will be added, in addition to further discussion of durational involvement in prominence realization. More examples of unEnglish features by Japanese learners and pedagogical suggestions will be introduced as well. PTLC2005 Tsutomu Sato The characteristics of placing prominences by Japanese Learners...5 References Bradford, Barbara (1988) Intonation in Context: Intonation Practice for Upper-intermediate and Advanced Learners of English. Cambridge University Press. Hayward, Katrina (2000) Experimental Phonetics. Longman. Johnson, Keith (1997) Acoustic and Auditory Phonetics. Blackwell. Rosen, Stuart and Peter Howell (1991) Signals and Systems for Speech and Hearing. Academic Press. Tench, Paul (1996) The Intonation Systems of English. Cassell PTLC2005 Tsutomu Sato The characteristics of placing prominences by Japanese Learners...6