Document 13945943

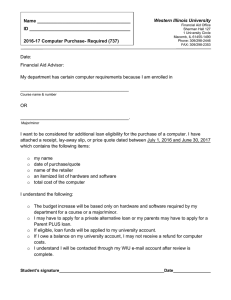

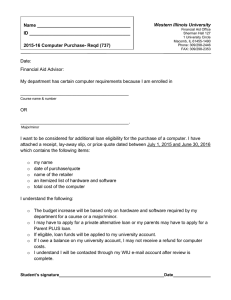

advertisement