Document 13939500

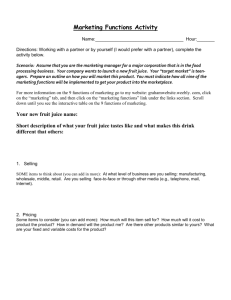

advertisement