THE HAZLIT T REVIEW

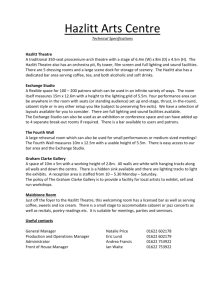

advertisement