Cetedocs Thesaurus

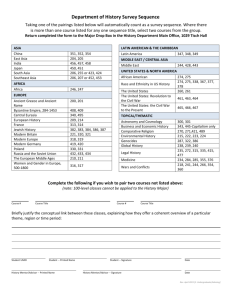

advertisement

IMEV or IPMEP number), word or phrase. One very useful and innovative feature is searching the texts by the LALME dialects identification (fig 9). The Corpus of Middle English Prose and Verse can be browsed and searched for words and phrases as a whole or within particular works. A proximity search for experience within 80 characters of auctoritee gives two matches both from the Canterbury Tales. Whilst a simple search for the phrase man of gret auctorite in the entire corpus brings no results, a Boolean search for all three words occurring together within a line or a paragraph brings twenty nine results, all from prose, though none of the phrase itself. Thirteen of these hits come from the Anthology of Chancery English which shows that though auctoritee itself was commonly used, Chaucers phrase at the end of the House of Fame was not a common legal (or other) set phrase. The disappointing absence of man of gret auctorite is interestingly counterbalanced by the presence of a lady of gret auctoritea search which gives one hit (fig 10). Cetedocs Thesaurus Formarum Totius Latinitatis Platform: Windows 3.1 or higher. Requirements: CD-ROM drive essential. Available from: Brepols Publishers NV, 68 Steenweg op Tielen, B-2300 Turnhout, Belgium. Tel.: +32 (0)14 402 500. Fax: +32 (0)14 428 022. http://www.brepols.com/ Price: BEF 75,000 single user. Network price on request. Cetedocs Thesaurus Formarum Totius Latinitatis (TF) describes itself as a Database for the Study of the Vocabulary of the Entire Latin World. It aspires to contain every attested form of every word in the Latin language from Plautus to the present day, together with information regarding the periods, authors, and works in which each form is found, and the frequency with which it appears in them. The package consists of a substantial printed version of the database, a more detailed electronic version on CD, and a small manual to accompany the retrieval software. The printed database contains an introduction to the database as a whole, and both that and the manual are written in French and English. The discussion below will be of the electronic database, unless specified. Content Fig.10 Incomplete as the results of this small investigation may be, they still prove useful. And the learning of all this and the searching itself only occupied around twenty enjoyable minutes of my time. The usefulness of searching the Corpus will increase proportionally to its size and we hope that the collection will continue to grow. Conclusions The Middle English Compendium is major achievement and a powerful resource of modern scholarship in Medieval English. Much of its capacity comes from the searchability and interconnectivity of its resources. The MEC is user-friendly, providing online help and explanations, and is fast and easy to navigate. Search forms require minimum typing, the results are clearly presented. Access to the project is subscription-based whilst at the same time is being continually developed. It functions successfully in its developing state and some effort has been made to provide guidance to the unfinished features. The resource remains open for potentially endless development, and with so much achieved already, it promises to continue being a tremendous contribution to Middle English scholarship. Elizabeth Solopova esolopova@britishlibrary.net Page 32 Spring 2000 Every text that has been used to prepare the database has been categorised under six headings: title, author, Clavis Patrum Latinorum number (where appropriate), size, century, and period. The latter refers to one of the four ages into which the TF divides the history of Latin: antiquitas (from Plautus to the end of the second century A.D.), aetas patrum (from Tertullian to the death of the Venerable Bede in 735), medium aevum (from 736 to 1499) and recentior latinitas (from 1500 to 1965, the last texts being those from the Second Vatican Council). Any one of these headings, or any combination of them, can be used to query the database: thus as well as the number of occurrences of the form amor in all Latin, one could find the frequency of the form Roma in all first century BC authors other than Virgil, or all forms that occur more than 3000 times in the patristic period, or, should one have the inclination, all the forms common to Cicero and St. Augustine but found nowhere else, which are found only once in those authors, and begin with letter t (there are four). Any result can then be displayed in progressively greater detail (e.g. frequency in various periods, in various authors, in various works), and in various orders (alphabetical, numerical, normal and reverse). The most detailed information available about any form is the title of the work or works in which it appears: for its exact location within the work, or for the actual text, one needs to look elsewhere (for example in the Thesaurus Patrum Latinorum or the PHI CD). A lot of thought has gone into the categorisation of the data: for example, works of any author are distinguished as authentic, dubious and spurious; the dating of a work to a century is categorised as either secure, doubtful, ambiguous or a terminus ad quem; a title Computers & Texts No.18/19 to the Latin-speaking world after the 2nd century AD. The first ten are christi, idest, christum, apostolus, ecclesiae, augustinus, david, iesu, iesus and ecclesiam, suggesting, we are told, a world of explanation, in which idest comes second, and also a world with the omnipresence of the Old and the New Testament. Fig.1. The results of a search for fulmen, showing the highest level of detail. thought to be due to the author of a particular work is included as part of that work, as opposed to those titles given to a work by others. A lot of effort has also gone into the categorisation of the forms, and perhaps one of the most powerful features of the electronic TF is its ability to deal with the differing orthographies and orthographical conventions (or lack of them) found in different authors and editors: with the printed database, as with many programs that exist for searching electronic databases, not only does one have to perform separate searches for each variant spelling of a word, but one also has to know what those variant spellings are. While this kind of problem occurs to an extent in classical Latin (especially with compounds such as adfero or affero), it is much more frequent in later Latin, with letters being doubled, added, removed or replaced with abandon (e.g. penitentia against paenitentia, nichil against nihil, screpitu against strepitu etc.). The introduction to the printed database gives examples of some of the most common ways in which spellings can vary, and the list is quite substantial. In the electronic database, however, all the hard work has already been done, and the variant spellings of any particular form are all linked together. This means, for example, that on consulting the TF one can discover that abundantia is found also as abandantia, abundancia, habundantia, and habundancia (this facility would make a handy tool in its own right), and then search for all five forms (or any selection from the five) simultaneously: clearly an extremely useful feature. What is it useful for? The uses to which this database could be put may be immediately obvious to some, but others may perhaps ask what (or who) is the TF actually for?. According to the notes accompanying the database, the TF provides an important source of information for the history of the Romance languages and of all the European languages influenced by Latin, and an initial opening to all Latinity and thus is a tool that brings hope. Exactly what kind of hope it brings is open to question, but the TF is certainly a useful tool for the study of language, enabling the user to discover the words which were common at any particular point in history, the words which were rare, and how this changed over time. A good example of one of the many kinds of analysis possible can be found in the introduction to the printed database, where the reader is presented with a list of all the forms that appear more than 1000 times, but do not appear in Antiquitas: that is, a list of all the most common forms that are new Computers & Texts No.18/19 It is hard to comment on the absolute usefulness of the TF, since it covers such a large time-span, and is thus potentially of interest to a number of different disciplines. However, it is clear that the TF is quite a flexible tool, and it may have something to offer to everyone, though of course exactly what it can offer and the resulting value for money may differ considerably. For those such as myself whose interest lies in Antiquitas, the TF has immediate advantages over the PHI CD when it comes to investigating how common a particular word is, or obtaining a list of forms unique to Vergil, for example, or a list of forms common to Propertius and Tibullus (though this is not the same as a list of words). The ability to search for variant spellings, and the powerful search facilities of the TF in general (it supports multiple individual and multi-character wildcards), are also extremely useful, and can point to forms missed with a careless search of the PHI CD. The database also has pedagogical potential: one can soon discover the most common forms in any particular author, or selection of authors, and use them as the basis for a specialised vocabulary list. One can also satisfy ones curiosity for pleasing trivia such as the ten most common words in classical Latin, which are (should anyone be interested) et, in, -que, est, non, ut, cum, ad, quod, and si. Help Documentation My acquaintance with the TF began with the manual, which did not prove to be an auspicious start. The manual is in two parts, the first containing the original French version, the second an English translation. Unfortunately, the translation is very poor, at times unreadable. This is an example from the first page: In the printed TF, the researcher has the list of the real forms attested in the works that means, the graphics such as they are printed in the editions. Throughout the manual, even simple features can be rendered unfathomable by such oracular pronouncements as With the Jump option you can set, during the display, the movement in function of the serial number of the displayed forms, and although there are a large number of screenshots to illustrate the text, they do not make up for the deficiencies of the translation. In general, the organisation of the material is poor, and important information is frequently hidden in the midst of seemingly unimportant text. A further problem is that the manual nowhere explains or even acknowledges the existence of two rather vital buttons (labelled Words and Lines) that are used for almost every search: they allow the user to choose an author, title, century etc. from a list, rather than type in the required form (e.g. saeculum -ii [dubium]) from memory. The buttons are mentioned, however, in the on-line help, which is available in English, French, German and Italian (one chooses a language each time the program starts), and tends to be more detailed than the manual. Help is available for each separate screen, usually in the guise of a screen-shot, clicking on the buttons of which reveals their function. There is a lot of useful information in the on-line help, though again its organisation could be improved with more cross-references and a better contents screen. My main criticism, however, is that a lot of the important information contained in the on-line help should really be in the manual (such as the two missing buttons, or details of how to retrieve results that Spring 2000 Page 33 one has saved), where it could be presented in a clear and logical order, the screen-specific (and un-ordered) online help being better suited to refreshing the memory. The manual does not provide a good introduction to the software, especially for the many potential users who are not at ease with technology, and who could easily be discouraged from getting the most out of the powerful software. While about an hours experimentation with the program, and occasional consultation of the on-line help, can provide the user with a good idea of how the TF works, such time is something of a luxury, especially if the CD is going to be used in a library, and I do not think I am alone in knowing a large number of academics who do not like to experiment with computers. Searching the Thesaurus Again, first impressions were not favourable: although the installation wizard successfully installed the program files to my designated folder C:\Classics Programs\CILF, it was unable to create a short-cut, the space between Classics and Programs in the folder name causing trouble. While this kind of problem was frequent in the early days of Windows 95, such a basic error should not be found in software written in 1998. Fig.2. Searching for Cicero. Despite a number of other bugs and design infelicities, to which I shall return later, the software does have its strong points. Once one gets used to the slightly non-standard interface, which does not take too long, it turns out to be very simple but very powerful, allowing the most frequently performed tasks to be accomplished quickly and easily. For example, supposing we wish to find the most common words in Cicero: clicking on the Auctor button on the main screen presents us with a new window (see Fig.2). The name of the author can then be typed into the search box, or selected from a list of authors (the words button, unmentioned in the manual). Clicking on the Next button reveals a list of Ciceros to choose from (authentic, dubious, etc.). Once the selection has been made, clicking on the Next button again allows the user to apply Boolean search terms to the various selected authors, clicking on Next again allows the user to specify a frequency: in this case we will be after forms that occur more than three hundred times. We are then returned to the main screen: here, should we wish, the search can be modified still further: the TF allows these results to be restricted to particular forms (e.g. forms that appear more Page 34 Spring 2000 than 300 times, and end in -orum), or linked via Boolean terms to any other search: so (for example) we could exclude from our Cicero search the most common forms from Antiquitas, which would exclude a lot of the uninteresting forms such as et, non, cum etc. from our results. The results are then displayed, and can be saved for later use, or exported to a text file for use in another program, or as a search argument for the Cetedoc Library of Christian Latin Texts. There are problems with the software, however: although the results can be sorted by frequency, for some mysterious reason they can only be sorted by their frequency in the entire database. In order to sort by their frequency in Cicero, one has to export the results to a text file, and then load them into a program such as Excel or Word and do the sorting there. The program can also take a long time to display the results, and during this time the computer appears to freeze: even on a PII 333, a search yielding a large number of results can lock up the computer for more than a minute, leaving the user unable to switch to any other application or do anything at all. Rather annoyingly, the TF does not support long filenames, so that when saving results the user is forced to return to the misery of obscure and unintelligible eight-letter cryptograms. Having saved a number of results, it was then quite difficult to retrieve them, as rather surprisingly one cannot load them in from the File menu (one has to load them through the Connections window): while the solution to this problem could be found in the on-line help (nothing in the manual), it was not easy to track down. As far as I am aware, the data cannot be copied to the hard-drive to speed up performance, as the program always reads from the CD. A rather more serious problem occurred with the printing: although the results were fine on one of the machines (running Windows NT 4 and printing to an HP LaserJet 8000), on the other, running Windows 95 and printing to a Canon Bubble-Jet 200ex, the text appeared in tiny print (about 4 point size) and there were no options to change it, thus making it impossible to obtain a hard copy of ones results without exporting them to a text-file and then loading them in another program. Conclusion The TF presents itself very much as work-in-progress: the introduction to the printed database acknowledges that given the ambitious scope of the project there are bound to be errors in the information contained within, and it stresses that this is the first of many releases. Indeed, even the program-icon reads TF1, suggesting that there will be a TF2 and a TF3 etc.. While I came across a number of minor errors in the database (one example of many: facta appears 30 times in Ovids Fasti, not 29), the frequencies were usually out only by one or two, which would not affect broad surveys of the Latin language: it was the manual and the software that seemed most in need of attention, especially given the high price of the database. If one can interpret the manual and ignore the bugs, however, the software is powerful and versatile, and the thought and effort that has gone into the preparation of the TF gives it the potential to be an extremely useful research tool. Matthew Robinson Balliol College, Oxford matthew.robinson@balliol.ox.ac.uk Computers & Texts No.18/19