feature

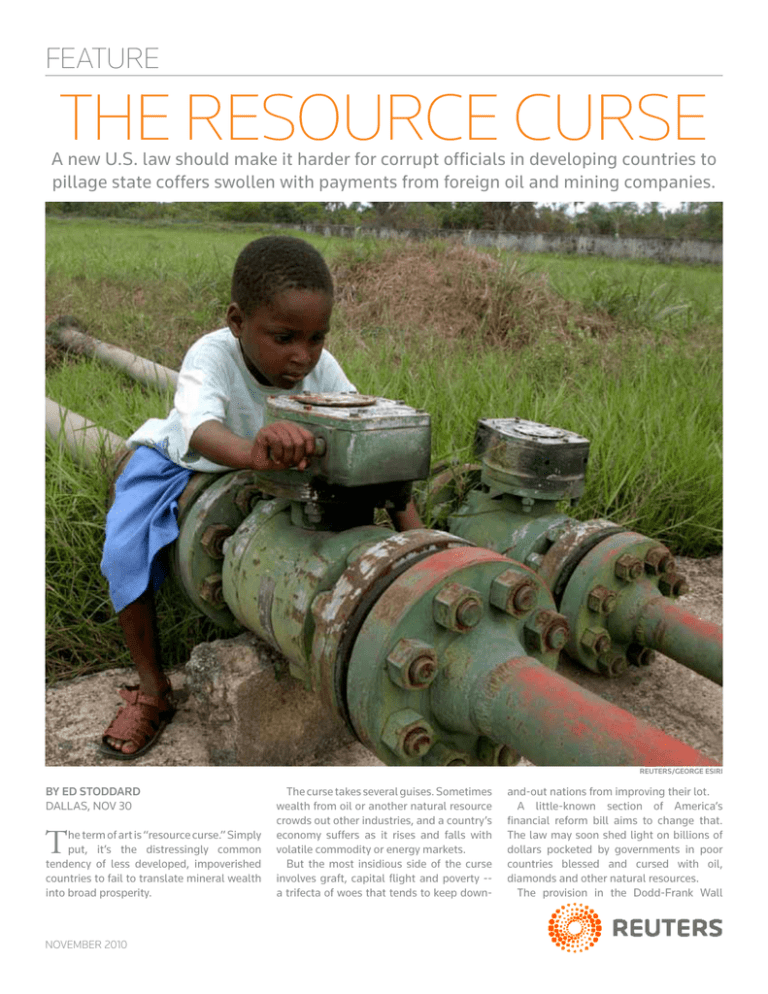

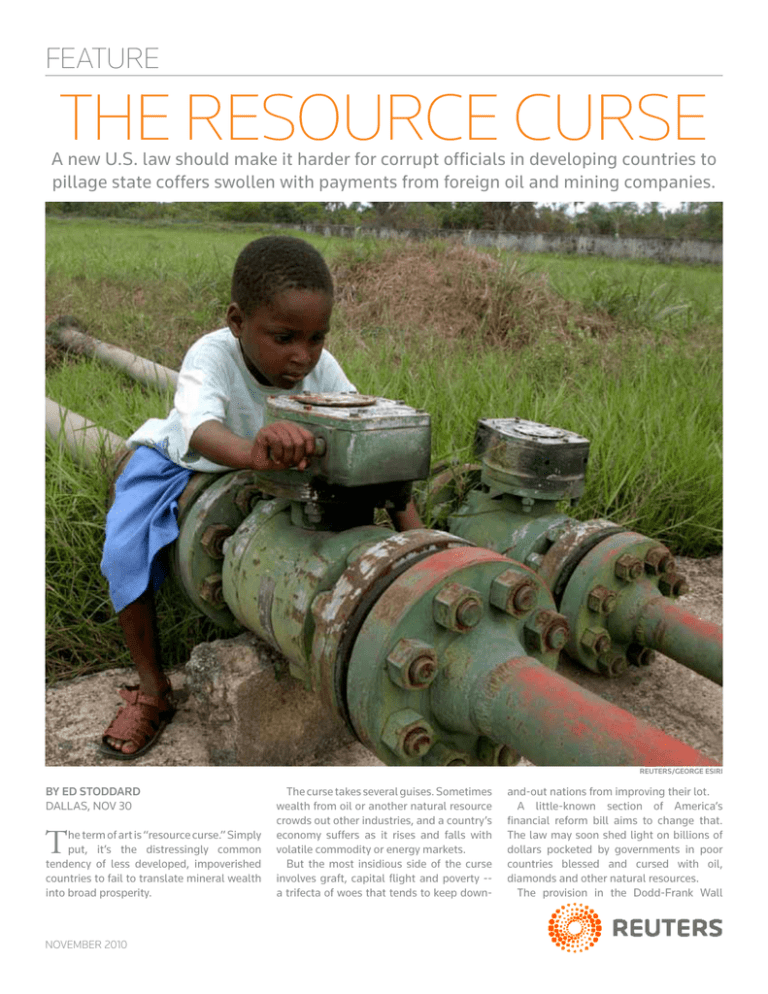

the resource curse

A new U.S. law should make it harder for corrupt officials in developing countries to

pillage state coffers swollen with payments from foreign oil and mining companies.

REUTERS/George Esiri

By Ed Stoddard

DALLAS, Nov 30

T

he term of art is “resource curse.” Simply

put, it’s the distressingly common

tendency of less developed, impoverished

countries to fail to translate mineral wealth

into broad prosperity.

november 2010

The curse takes several guises. Sometimes

wealth from oil or another natural resource

crowds out other industries, and a country’s

economy suffers as it rises and falls with

volatile commodity or energy markets.

But the most insidious side of the curse

involves graft, capital flight and poverty -a trifecta of woes that tends to keep down-

and-out nations from improving their lot.

A little-known section of America’s

financial reform bill aims to change that.

The law may soon shed light on billions of

dollars pocketed by governments in poor

countries blessed and cursed with oil,

diamonds and other natural resources.

The provision in the Dodd-Frank Wall

NATURAL RESOURCESnovember 2010

FOR AND AGAINST

The battle lines are already emerging.

Exactly what form the the new rules will take

is still being negotiated.

Many U.S. companies and industry groups

oppose the change, fearing it will make it

tougher to compete with their Chinese rivals.

But the provision has spawned an unusual

alliance between anti-poverty campaigners

and some Wall Street investor groups

backing it.

For their part, activists are hoping greater

transparency will make it harder for corrupt

governments to siphon off funds that should

be used for the general population. As for

investor groups, they are counting on the law

to make it easier to judge the risks -- criminal

or otherwise -- being taken by companies in

frontier markets where information is often

hard to come by.

It aims to lift the veil of secrecy that shrouds

financial flows and extractive industries

because it will provide a far more detailed

picture of how much money governments are

actually raking in from the energy and mining

companies operating within their borders.

Paul Bugala, a sustainability analyst

with Calvert Asset Management Company,

which has almost $15 billion in assets under

management, said changes in tax and royalty

policies in resource-rich countries can have a

dramatic impact.

“This (provision) can help investors gauge

when this is happening,” he said, pointing to

Shell in Nigeria as an example. In a briefing

Disappearing money in Africa

According to Global Financial Integrity, a non-profit advocacy group, total illicit financial outflows

from Africa, conservatively estimated, were approximately $854 billion from 1970 to 2008.

Top 5 African countries financial outflow – $ billions

Nigeria

Egypt

Algeria

Morocco

South Africa

0

20

40

60

80

29/11/10

Street Reform and Consumer Protection

Act will require much more transparency

from companies in the so-called extractive

industries -- miners and energy companies

-- on payments to foreign governments. The

idea is to make it harder for corrupt officials

to pillage state coffers swollen with royalty

and other payments from foreign oil and

mining companies.

This is no trifling amount of money.

As an example of what is at stake, an

estimated $27.5 billion flowed illicitly out

of oil-rich Nigeria in 2009, according to

calculations provided exclusively to Reuters

by Global Financial Integrity (GFI), an

advocacy group that tracks such trends. That

sum is part of a much wider stream of illicit

money being channeled from resource-rich

countries in the developing world to banks

and tax havens elsewhere.

In a report earlier this year, GFI estimated

that Africa alone lost $854 billion in illicit

flows from 1970 to 2008.

100

Source: Global Financial Integrity

Reuters graphic/Stephen Culp

“This (provision)

can help investors

gauge when this is

happening.”

circulated to the investment community,

he noted: “The oil and gas output of Shell’s

subsidiary in Nigeria ... dropped by 65

percent from 1.05 million barrels per day in

2005 to 360,000 barrels per day in 2008

due to shutdowns caused by conflict in the

Niger River Delta.”

“The full impact of Shell’s drop in

production in Nigeria between 2005 and

2008 and its plans for the country cannot

be modeled completely without information

regarding the related tax, royalty and other

obligations.”

The net that has been cast here is wide. It

will include not only companies such as oilgiant Exxon that have their domiciles in the

United States but also any energy or mining

company registered with the SEC because of

secondary listings.

By some U.S. congressional estimates, this

may include 70 percent of publicly-listed

international oil and mining companies and

the net will almost certainly widen.

The European Commission has launched

public consultations on the issue, noting

the reporting requirements for extractive

industries laid down by Section 1504 of the

Dodd-Frank Act, which it says may become

global accounting standards.

The International Accounting Standards

NIGERIAN LIFE: A boy takes a break from swimming in the

polluted waters of the Makoko fishing community in Lagos

November 21, 2009. REUTERS/Goran Tomasevic

Board is considering a standard for extractive

industries that could be similar, but while the

process is underway it could take years.

And according to U.S. congressional

sources, British politicians are signaling their

intention to craft similar legislation to be

applied to UK-listed firms in the sector.

“There have been inquiries made to me

about how to get this legislation done

by parliamentarians in England ... I have

2

NATURAL RESOURCESnovember 2010

SPREADING THE WEALTH: Workers protest in the streets of Nigeria’s commercial capital Lagos May 13, 2009. REUTERS/Akintunde Akinleye

had communication with London, there is

certainly interest there,” said Ben Cardin, a

Democratic senator from Maryland.

PROJECT BY PROJECT

Cardin and Barney Frank -- the

Massachusetts Democrat who will chair the

House of Representatives Financial Services

panel until January -- both invoked the

“resource curse” in interviews with Reuters

when speaking to their motivation for

pushing for the provision.

Supporters see the U.S. move as a

welcome addition to the Extractive Industries

Transparency Initiative (EITI), launched by

former British Prime Minister Tony Blair at the

World Summit on Sustainable Development

in Johannesburg in 2002.

Critics say the EITI’s main weakness lies in

the fact that governments have the option

of signing up for it and many resource-rich

nations with transparency issues, such as

Angola, Saudi Arabia and Russia, have not

signed up. Dodd-Frank gives companies no

choice, regardless of where they operate.

Cardin, with his senate Republican

counterpart Richard Lugar, was instrumental

not only in bringing the legislation forward

but also in inserting a key provision that

requires project-by-project reporting by

Find more Reuters special reports at

our blog The Deep End here:

http://link.reuters.com/heq72q

companies. The clause was the subject of

behind-the-scenes lobbying by the likes of

billionaire liberal activist George Soros.

“Project-by-project is a remarkable degree

of disclosure. Normally companies go by their

payments to whole regions or on a global

scale and you can’t unpick those numbers to

work out what happened in each country,”

said Nicholas Shaxson, a Swiss-based

analyst with British think-tank Chatham

House who has written extensively about oil

and transparency in Africa.

A handful of mining and energy companies

registered with the SEC already provide

detailed information on their payments to

governments -- they include South African

gold miner AngloGold Ashanti, U.S. gold

miner Newmont, and Canadian energy firm

Talisman.

But the project level of such payments will

require far more disclosure in most cases.

“This matters because it allows local

ROCKS: A visitor holds a 17 carat diamond at a Petra

Diamonds mine in Cullinan, outside Pretoria, South Africa,

January 22,2009. REUTERS/Siphiwe Sibeko

communities to identify the exact nature of

revenue streams. Where this might matter is

Zambia where a small number of companies

is involved in lots of different concessions,”

said Alex Cobham, the chief policy adviser for

British charity Christian Aid.

“If the project in your area is doing well

then you have something where you can hold

3

NATURAL RESOURCESnovember 2010

your government to account and if the project

is doing badly or at least appears not to be

making a great return you can ask questions

about whether that is a true reflection of

what’s happening,” he said.

But Cobham said that even when this is

the case, tracing where funds may have gone

after being collected by corrupt governments

remains shrouded in a tax haven haze and on

this front, critics complain little of substance

has been done.

SEC BATTLEGROUND

Lobbies from both sides are pushing the

SEC to have the legislation either de-fanged

or given a serious bite.

“We do feel that it will place U.S. listed

companies at a competitive disadvantage.

We feel like that because it requires projectlevel payment disclosures,” said Misty

McGowen, head of Federal Relations at the

American Petroleum Institute (API), a lobby

group that represents over 400 oil and gas

companies.

“When

U.S.-listed

companies

are

competing for global energy resources, nonU.S. listed companies will have public access

to confidential proprietary information that

gives them a competitive advantage,” she

told Reuters.

The API is also concerned about the fact

that it does not seek participation or input

from host governments. In its submission

to the SEC, it asked that project-by-project

disclosure be dropped and that requirements

be limited to the country level. It also asked

for “an exemption that allows companies

not to disclose payments for countries

that prohibit such disclosure” and one “for

situations where disclosure by country in

effect provides disclosure of commercially

sensitive information for a single project or

field.”

But there is also investor support for the

initiative.

In a Nov. 15 submission to the SEC, Calvert

Investments and the Social Investment

Forum said “resource-producing operating

environments pose regulatory, taxation,

political, and reputational risks that current

reporting required of resource extraction

issuers does not address adequately.”

Calvert said in its submission that the

extractive industry provisions in Dodd-Frank

were vital tools in the assessment of equity

valuations of companies in the industry.

“The calculations and assumptions made

in this process, especially those regarding

a particular project’s exposure to political

UNDERGROUND RICHES: A mine worker walks along an underground tunnel in a Petra Diamonds diamond mine in Cullinan,

outside Pretoria, South Africa, January 22, 2009. REUTERS/Siphiwe Sibeko

and other transparency-related risks, would

be enhanced greatly with the specific data

provided by (the legislation) as it is written,”

it said.

The next battles may come in the European

Union and Britain as pressure comes for them

to adopt similar rules.

And as the API notes, conflict also looms

where the SEC rules for disclosure rub up

against country-specific ones that don’t

allow them, for whatever reason.

But in such cases, American law often

comes on top,

“It’s not uncommon for U.S. law to run

afoul of foreign law. But the companies tend

to comply with U.S. law because we actually

enforce our law,” said Heather Lowe, director

of government affairs at Global Financial

Integrity.

(Editing by Claudia Parsons

and Jim Impoco)

4

NATURAL RESOURCESnovember 2010

factbox

UPHILL BATTLE:

A truck loaded

with limestone

is driven up a hill

at the Dangote

cement mine in

Obajana village

in Nigeria’s

central state of

Kogi November

8, 2010.

REUTERS/

Akintunde

Akinleye

A

provision in the Dodd-Frank Wall Street

Reform and Consumer Protection

Act will require much more transparency

from companies in the so-called extractive

industries -- miners and energy companies

-- on payments to foreign governments.

Here are some other initiatives aimed

at bringing transparency to extractive

industries, which are seen as one of the

primary sources behind tens of billions of

dollars in illicit financial flows.

Transparency

initiatives for

extractive

industries

Natural resources and transparency

The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative is a voluntary program that aims to improve accountability in

the mining and energy sector.

EITI status*

Compliant

Candidate

Other

INTERNATIONAL ACCOUNTING

STANDARDS BOARD (IASB)

THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION

The European Commission has

launched public consultations on the

matter, noting the IASB initiative as well as

the provisions in the U.S. legislation.

g

EXTRACTIVE INDUSTRIES

TRANSPARENCY INITIATIVE (EITI)

g The Extractive Industries Transparency

Initiative was launched by former British

Prime Minister Tony Blair at the World

Summit on Sustainable Development in

Johannesburg, South Africa, in 2002.

The EITI is a coalition of governments,

companies and investors with the goal of

getting companies to publish what they

pay and governments to disclose what they

29/11/10

g The IASB is currently working on

developing a country-by-country reporting

requirement for extractive industries. The

process could take years but once finalized,

the standard is likely to become mandatory

in the European Union which typically

endorses its standards.

* A country that has fully met four EITI sign-up indicators becomes a candidate country. Once a country has obtained the

candidate status it has two years to be validated as a compliant country. Countries marked “other” have signaled their intent

to implement the EITI.

Source: Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative

Reuters graphic/Stephen Culp

receive. It has been hailed as a welcome

first step in the process that among other

things has helped raise awareness about

the issue.

But critics say one of its weaknesses lies in

the fact that governments have the option

of signing up for it and many resource-rich

nations with transparency issues, such as

Angola, Saudi Arabia and Russia, have not.

And even among candidate countries

-- so-called because they have met four

“sign-up” indicators -- analysts say it often

falls short of its goals.

One recent report for British think-tank

Chatham House about the initiative in

Nigeria concluded: “The original goals

of EITI were to improve accountability

and governance; over time, in the face

of embedded realities, these objectives

appear to have been whittled down, and

those operating within NEITI (Nigeria’s

EITI) are setting themselves more modest

goals.”

(Sources: Reuters; EITI; IASB; ‘Nigeria’s

Extractive Industries Transparency

Initiative: Just a Glorious Audit?’ Chatham

House paper, Nov 2009,

by Nicholas Shaxson)

(Reporting by Ed Stoddard)

5

NATURAL RESOURCESnovember 2010

factbox

C

Tracking illicit financial flows

alculating the amount of money

that disappears from poor countries

as a result of corruption is complicated.

Advocacy group Global Financial Integrity

(GFI) estimates that Africa lost $854 billion

in illicit financial flows from 1970 to 2008,

much of it from resource-rich states.

There are two main methods that

economists use to measure illicit financial

flows out of countries: the World Bank

residual method and trade mispricing.

The following are some details about the

methodologies which are used by GFI.

THE WORLD BANK RESIDUAL METHOD

relies on balance of payments data that is

reported by all member countries of the

International Monetary Fund under the

Special Data Dissemination System. This

data must be reported in a timely manner

and so it is available on a regular and

annual basis.

The method basically takes the two broad

sources of funding that a country has -external borrowing (including official aid)

and net foreign direct investment (FDI). It

matches them up with the use side of the

equation, which is the deficit on the current

g

account and the change in official reserves.

The latter, among other things, tracks any

external debt repayments that have been

made on behalf of the country.

Broadly speaking, it is the gap between a

country’s source of funds over a given time

and its use of funds over the same period,

which highlights illicit or unexplained

capital flows.

For example, let’s say Country X brought

in $10 billion in net FDI and external

borrowing but its use of these funds, as

shown by the current account deficit (the

difference between exports and imports

which needs to be funded) and the change

in reserves, came to $5 billion. That leaves

$5 billion unaccounted for, which must

have leaked out of the balance of payments

in unrecorded flows. The two figures should

balance out, as in an accounting balance

sheet.

How does it work? Let’s take a hypothetical

example of export under-invoicing. Say that

I’m an Indian tea exporter. I tell the Indian

government that I am exporting $3 million

worth of tea to a buyer in the United States.

But on the U.S. side, the import is reported

to be worth $5 million. Where did the other

$2 million go that the American buyer

shelled out? Probably into my off-shore

bank account.

One way to measure trade mispricing is to

look at official bi-lateral trade data, though

there may be technical problems in the

accurate recording of trade statistics.

For example, exports from hypothetical

country Manchukistan to the United States

may officially be $30 billion for a set year.

But U.S. authorities may have recorded $50

billion in imports from Manchukistan. The

$20 billion gap here would be unaccounted

for illicit flows that went somewhere else.

TRADE MISPRICING, which tracks

commercial corruption, involves the underinvoicing of exports and the over-invoicing

of imports (or vice versa). On a global

scale it is believed to account for about 60

percent of illicit financial flows.

(Sources: Global Financial Integrity (GFI);

Interview with GFI economist

Dev Kar; World Bank)

((Reporting and writing by Ed Stoddard;

Editing by Claudia Parsons))

g

NIGERIA’S POOR: A girl paddles a traditional canoe in

the Makoko fishing community in Lagos November 21,

2009. REUTERS/Goran Tomasevic

6

NATURAL RESOURCESnovember 2010

OIL WEALTH: A

ship berths on the

shore of a lagoon

as it discharges

fuel at a company

in Nigeria’s oil

hub city of PortHarcourt July 7,

2010. REUTERS/

Akintunde

Akinleye

COVER PHOTO: A child plays with a pipe near an oil well in Olomoro village in Isoko, a local government area of the Delta region in Nigeria, March 28, 2007. REUTERS/George Esiri

For more information contact:

Jim Impoco,

Enterprise Editor, Americas

+1 646 223 8923

jim.impoco@thomsonreuters.com

Claudia Parsons,

Deputy Enterprise Editor

+1 646 223 6282

claudia.parsons@thomsonreuters.com

© Thomson Reuters 2009. All rights reserved. 47001073 0310

Republication or redistribution of Thomson Reuters content, including by framing or similar means, is

prohibited without the prior written consent of Thomson Reuters. ‘Thomson Reuters’ and the Thomson

Reuters logo are registered trademarks and trademarks of Thomson Reuters and its affiliated companies.

edward stoddard

+1 972 632 7041

edward.stoddard@thomsonreuters.com