Document 13885791

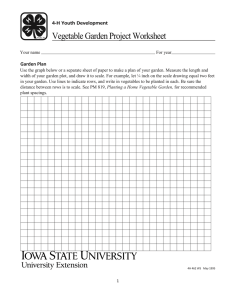

advertisement